eBook - ePub

Managing Cultural Heritage

Ecomuseums, Community Governance, Social Accountability

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Managing Cultural Heritage explores managerial and governance issues within the cultural heritage sector, with particular regard to the ecomuseum. Moreover, a social accountability model is supplied to ecomuseums in order to be accountable towards its shareholder, the local community.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Managing Cultural Heritage by M. Magliacani in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & International Business. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: How to Manage Cultural Heritage in Times of Crisis

Abstract: During the actual crisis period, cultural organizations must be able to achieve their mission, which consists in preserving and enhancing public cultural heritage, by managing a shrinking budget. Moreover, because of the public value and utility of the service provided, they have to “learn” how to combine the criteria of sociability, with economy and infra-intergenerational equity ones. Consequently, cultural organizations get engaged in processes of “managerialization” as well as the other organizations operating, in various legal forms, within the entire public sector. From these standpoints, this first chapter aims at introducing the cultural heritage management issues in times of crisis, under the New Public Management and the Governance frameworks.

Magliacani, Michela. Managing Cultural Heritage: Ecomuseums, Community Governance and Social Accountability. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. DOI: 10.1057/9781137481559.0005.

Various socio-economic changes have occurred over the last century in the international scenario, such as the spreading of advanced technologies, the increased level of communication and the ageing population trends.1 All of these factors have contributed to validate within the developed economies, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, based on human innate curiosity.2 This model, represented by a pyramid, ranks at the top of the “self-actualization” needs scale, in which the desire to know and understand is included (Maslow, 1943: 384). This kind of need is mostly fulfilled by intangible (services) rather than tangible goods (products). This is the reason why the so-called “service economy” and the “service science” (Spohrer and Maglio, 2008: 239) have been developing at an international level. According to one of the most common definitions provided by management literature, services consist in “a time-perishable, intangible experience performed for a client who is also acting in the role of the co-producer that transforms the state of the client” (Spohrer and Maglio, 2008: 240). These services include those deriving from the management of cultural heritage. Cultural service is relating to that which delivers knowledge and contributes to educate. In fact, “repeated experience of culture transforms its customers by allowing them to grow in educational, aesthetic and curiosity dimensions” (Muñoz-Seca, 2011: 3). Hence, the gap between the “cultural demand” of actual generations as well as future generations and the scarce resource available to manage cultural heritage has been growing in those countries where the cultural and natural resources represent a strategic factor for economic development.

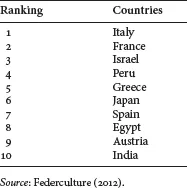

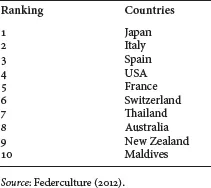

How to preserve and enhance public, cultural and natural heritage3 with a shrinking budget represents a critical issue for politicians, entrepreneurs and people of social communities (Muñoz-Seca, 2011). The risk of a decreasing quality of life for the present and future generations is becoming a reality, because of the negligent behaviour towards cultural heritage. Mostly due to the global crisis, the political choice to increasingly reduce the slice of the “public financial pie” aimed at the cultural heritage sector is largely spreading, even in countries rich in these resources such as Italy. Regarding the latter, for instance, the Annual Report of “Federculture”, an Italian Bureau of Public Cultural Service, Tourism, Sport, and Leisure, ranked Italy first in the top 10 list of cultural heritage brand index countries (Table 1.1) and fifth in the top 10 tourism destinations list (Table 1.2).

TABLE 1.1 The Country Brand Index: the top 10 cultural heritage list

TABLE 1.2 The Country Brand Index: the top 10 tourism destination list

Moreover, according to the “Unioncamere” Annual Report, the Italian cultural system (cultural industries, creative industries, the historical artistic and architectural heritage and the performing and visual arts) generates 5.4% of the country’s total wealth, and gives jobs to 1,400,000 people (5.6% of the total employment).

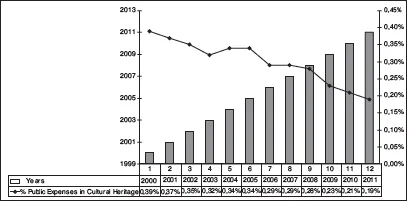

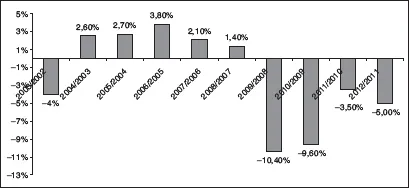

In spite of the aforementioned records, during the last 12 years, the percentage of the public budget addressed towards cultural heritage has been falling under 1% (Figure 1.1) against 2.7% of France and 2.4% of Germany (Arts and Business, United Kingdom, 2011; Public Funding of Culture 2011). According to Federculture (2012), the public findings predominate in Europe, Canada, Australia while it is vice versa in the USA, UK and Japan non-profit cultural organizations aided by private sources. Indeed, the low level of sponsorship for Italian cultural heritage is still being decreased (Figure 1.2).

The interest in avoiding the negative consequences of a careless management of those public goods has stimulated an interdisciplinary debate on this common issue. Which kind of tool can be used by the social community to take care of its cultural and natural resources? What public support has been expected by cultural organizations (museums, parks, archives, etc.) in charge of managing such common goods? How does management accounting research try to answer the previous questions?

FIGURE 1.1 The state cultural heritage budget

Source: Federculture (2012).

FIGURE 1.2 The cultural heritage sponsorships

Source: Federculture (2012).

This topic has been developed more under economic and sociological viewpoints rather than in the managerial accounting perspective. Indeed, cultural heritage organizations represent a developing research field for managerial accounting scholars. The reason is mainly twofold: the firm-centralism of the mainstream management on the one hand, and on the other the difficulties met by management scholars to have a productive dialogue with those who manage cultural goods, even operating within the public field. With regard to the first reason mentioned, the cultural heritage sector is opening up towards groups largely composed of institutions that are branches of the public body or organizations that depend on public funding (Zan et al., 2000: 336); therefore cultural heritage issues have always been discussed as public administration and policy studies topics (Jackson, 1988; Landry, 1994). In management accounting research, this specific organizational context started being explored in the mid-1990s, because of the growing interest to assign an appropriate monetary value to collections for financial reporting purposes (Boreham, 1994; Carnegie and Wolnizer, 1995; Carman et al., 1999). The discussion on this technical issue (accounting system), still an object of debate among academics and professionals, was promptly extended to the managerial issue (accountability). Thanks to the Australian scholars (Carnegie and Wolnizer, 1996), the adoption of an accrual accounting system has been advocated for the public sector financial management as well as the report based on a range of financial quantitative information and qualitative data enabling accountability in museums. It is no wonder that Australian museums have been exploring pilot cases in the management accounting research. Indeed, Australia belongs to the group of OECD countries (New Zealand, Canada, Sweden and UK) where the public administration reform, against the economic crisis and the high-level cost of public service and wealth,4 was set up in the late 1970s. At the heart of that reform was a shift towards a new style of running public resources and service, based on the accountability paradigm. The latter occurred in so many countries during the 1980s that it was labelled “New Public Management” (Hood, 1995: 104). The key elements of New Public Management (hereafter NPM) consist in “lessening or removing differences between the public and the private sector and shifting the emphasis from process accountability towards a greater element of accountability in terms of results” (Hood, 1995: 94). The doctrinal components of NPM are divided into two categories: Public Sector Distinctiveness and Rules vs Discretion. The first one is composed of the key elements summarized in the following points (Hood, 1995: 96):

1Unbundling of the public sector into corporatized units organized by product;

2More contract-based competitive provision, with international markets and term contracts;

3Stress on private sector style of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Introduction: How to Manage Cultural Heritage in Times of Crisis

- 2 The Ecomuseum Under a Managerial Perspective

- 3 The Governance Framework in the Ecomuseum Context

- 4 The Ecomuseum Practices: An International Overview

- 5 The Tuscan Experience

- 6 Which Accountability for the Ecomuseum: A Community Governance Scorecard Model

- 7 Closing Remarks

- Appendix

- References

- Index