eBook - ePub

Decarbonization in the European Union

Internal Policies and External Strategies

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Decarbonization in the European Union

Internal Policies and External Strategies

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The authors examine how far internal policies in the European Union move towards the objective of reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the EU by 80-95 per cent by 2050, and how or whether the EU's 2050 objective to 'decarbonise' could affect the EU's relations with a number of external energy partners.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Decarbonization in the European Union by Sebastian Oberthür, Sebastian Oberthür,Kenneth A. Loparo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Environment & Energy Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Decarbonization in the EU: Setting the Scene

Claire Dupont and Sebastian Oberthür

Introduction

Climate change is a challenge that requires long-term, cross-sectoral and cross-border action. It is often described as one of the most complex problems facing humankind – one that affects the entire planet and all aspects of modern society (Haug et al., 2010). The European Union (EU) is not immune to the challenges of mitigating and adapting to climate change. Human-induced climate change is caused by the emission of potent and long-lived greenhouse gases (GHGs), which has increased since pre-industrial times (IPCC, 2013). Reducing GHG emissions quickly enough to a level that will prevent ‘dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system’ (UNFCCC, Article 2) means transforming our infrastructure, energy, transport, agriculture and industrial sectors away from fossil fuels.

The EU has long-held ambitions to demonstrate global leadership by example in responding to climate change, including through developing ambitious domestic policies (for example, Oberthür & Roche Kelly, 2008; Schreurs & Tiberghien, 2007). In October 2009, the European Council of heads of state and government agreed on an ambitious, long-term climate policy objective to demonstrate the EU’s willingness to play a leading role in limiting global temperature increases to 2ºCelsius (European Council, 2009). This agreed objective is to reduce GHG emissions in the EU by 80–95 per cent by 2050, compared to 1990 levels. Such an objective is in line with scientific estimates of the required action to avoid catastrophic climate change (IPCC, 2007; 2013).

Reducing GHG emissions to such a degree effectively means decarbonizing the EU. It requires eliminating emissions in a number of sectors of society and limiting emissions considerably elsewhere. As it especially requires a virtual phase-out of carbon dioxide emissions from the use of fossil fuels, this ambition is therefore often referred to as ‘decarbonization’. Throughout this book, it is in the context of the objective to reduce GHG emissions in the EU by 80–95 per cent by 2050 that we use the term ‘decarbonization’.

This volume explores what the 2050 decarbonization objective means in practice: first, for internal policies within the EU, and second, for external EU energy relations. Authors explore the EU’s internal policies and external energy relations to see if they are in line with climate objectives to 2050. Are internal policies equipped to move towards and achieve decarbonization? Are external energy relations prepared for the transition that is unfolding? The challenges arising from decarbonization are only amplified by the contexts of economic and financial crises in Europe from 2008 onwards, political tension with Russia from 2013 onwards and changing geopolitics, given the rise of powers such as China, India, Brazil, among others. This book provides an assessment of the state of the art of EU internal policies and external relations and discusses how decarbonization should or could influence their development.

In this introductory chapter, we briefly discuss the historical development of EU climate policy in line with international climate developments. Next, we present the 2050 perspective, the nature of the 2050 objective and the many scenarios and roadmaps that describe options for achieving the decarbonization objective. We then introduce the key questions and accompanying conceptual framework guiding the contributions to the book. Finally, we provide an overview of the organization of the book and its chapters.

1. Development of EU climate policy

EU policy on climate change first developed in response to international developments. It was not until the 1980s that EU institutions began seriously considering climate change as an area for internal policy development – largely in response to international negotiations that eventually led to agreement on the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 1992. EU climate policy was often based on legal competences in the areas of the environment and the internal market. These competences allowed EU institutions to make progress on climate policy relatively quickly after the issue came onto the agenda (see, also for the following, Jordan et al., 2010; Oberthür & Pallemaerts, 2010; Wurzel & Connelly, 2011).

Throughout the 1990s, the EU moved forward in small steps on climate policy. In the international negotiations on what became the Kyoto Protocol to the UNFCCC in 1997, the EU proposed to reduce its GHG emissions by up to 15 per cent compared to 1990 levels by 2010. While this target was eventually lowered to a GHG emission reduction of 8 per cent under the Kyoto Protocol, this was still the most ambitious commitment by any party to the Protocol (Oberthür & Pallemaerts, 2010). Several EU climate-related policy measures were agreed in the 1990s and first half of the 2000s, including on GHG emissions monitoring (Council Decision 93/389/500/EEC and subsequent revisions in 1999 and 2004); energy efficiency (for example, Council Directive 93/79/EEC to improve energy efficiency, ‘SAVE’; see Chapter 7); renewable energy (Council Decision 93/500/EC on the promotion of renewable energy sources, ‘ALTENER’ and Directive 2001/77/EC); emissions trading (Directive 2003/87/EC); and reducing emissions of fluorinated GHGs (Directive 2006/40/EC and Regulation EC 842/2006).

In the mid-2000s, the pace of internal EU climate policy development quickened, spurred on by several factors. First, climate policy became a driver of European integration more broadly. In the wake of the failed EU Constitutional Treaty, climate policy was reframed as an opportunity to reinforce the legitimacy of the EU and its institutions. Second, discussions on the security of energy supplies, given Europe’s great energy import dependence (see also Chapter 8), provided an added impetus for more climate policies that would lead to enhanced domestic generation of renewable energy and increased energy efficiency. Third, the role of the EU in the international system and its strong support for multilateralism also provided added motivation to advance on climate policy (Roche Kelly et al., 2010, pp. 14–15).

Climate change was thus a matter of high politics by the time the EU came to agreeing internal policies to 2020 in 2007. Ambitions for 2020 were summarized in the 20-20-20 commitment: to reduce GHG emissions in the EU by 20 per cent by 2020 compared to 1990 levels; to increase the share of renewable energy in EU final energy consumption to 20 per cent by 2020; and to improve energy efficiency in the EU by 20 per cent compared to business-as-usual projections for 2020. Of these three goals, only the first two are binding. The energy efficiency target is an aspirational goal, although later policy measures were agreed to try to achieve the target (such as the Energy Efficiency Directive 2012/27/EU; see also Chapter 7). Adopted in 2009, the package of policy measures aiming to achieve the 2020 goals included a revised Emissions Trading Directive (2009/29/EC), a new Renewable Energy Directive (2009/28/EC), a Directive providing a legal framework for Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) technology (2009/31/EC) and a new Effort Sharing Decision (No. 406/2009/EC), allocating the amount of emissions each member state must reduce in sectors not covered by the Emissions Trading System (ETS). A regulation reducing the emissions of carbon dioxide from new passenger cars (No. 443/2009) was also negotiated and agreed alongside the climate and energy package, as was the inclusion of international aviation in the ETS (Directive 2008/101/EC). The ‘climate and energy package’ of 2008/09 contributed to proclamations that, perhaps, the EU had finally achieved a high level of integration of climate and energy policies (see, for example, Adelle et al., 2012). The package was eventually reflected in the Doha Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol, adopted in 2012, in which the EU agreed to reducing its GHG emissions by 20 per cent compared to 1990 levels during a second commitment period of the Protocol (2013–2020).

EU climate policy development has levelled off since the 2000s. The 2000s had seen a noticeable acceleration of climate policy development at the EU level, with the climate and energy package of 2008/09 marking a significant step for harmonization and communitarization of this policy area. In the wake of the financial and economic crises from 2008 onwards and the backlash of international climate policy at the 2009 Copenhagen climate summit, EU climate policy has become less dynamic. The climate and energy package has certainly been further implemented, and several new legislative acts (including Regulation (EU) No 517/2014 on fluorinated GHGs, Regulation (EU) No 333/2014 on carbon dioxide emissions of passenger cars and the Energy Efficiency Directive 2012/27/EU) have updated and strengthened the existing climate policies. However, discussions on developing the cornerstones of the EU’s climate policy – the EU ETS, renewables and effort-sharing among the EU member states – have generally progressed at snail’s pace. One illustration of this trend is the long and heated debate about postponing the auctioning of a certain amount of emission allowances (known as ‘backloading’) as a modest short-term measure to address the oversupply in the EU ETS. This measure was eventually passed in 2013, but more structural solutions to the problem continued to face an uncertain fate (Marcu, 2012).

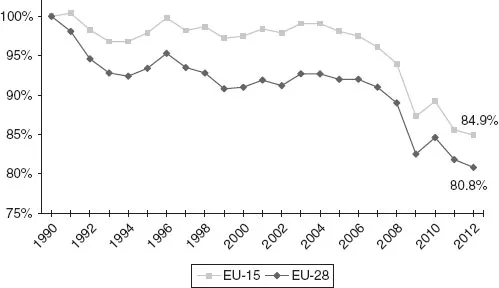

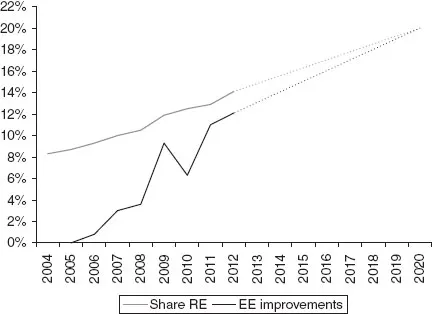

As of 2014, the EU is nevertheless on its way to achieving a 20 per cent reduction in GHG emissions by 2020, and it will most likely achieve its renewable energy goal also. While the EU-15 (that has an 8 per cent reduction target under the Kyoto Protocol for 2008–2012) had achieved reductions of slightly over 15 per cent by 2012, the EU-28 had already achieved GHG emission reduction of over 19 per cent (see Figures 1.1 and 1.2). At the same time, GHG emissions in the EU-28 could decrease by more than 24 per cent by 2020, in excess of the 20 per cent reduction target (EEA, 2014, p. 42). The energy efficiency goal can also be achieved, but further implementing measures to 2020 are likely to be required (see Figure 1.2; EEA, 2014, p. 75; European Commission, 2014a, p. 4).

Figure 1.1 GHG emissions in the EU-28 and EU-15 between 1990 and 2012

Source: European Environment Agency GHG data viewer (eea.europa.eu, date accessed 31 July 2014).

In January 2014, the European Commission proposed a new policy framework for climate and energy policy to 2030, as an interim step to the 2050 objective (European Commission, 2014b). A single GHG emission reduction target of 40 per cent by 2030, compared to 1990, and an EU-wide objective for expanding the share of renewable energy to 27 per cent are to drive the required transition. In mid-2014, the Commission furthermore suggested a 30 per cent target for energy efficiency for 2030. In October 2014, the European Council agreed to adopt the 40 per cent GHG emission reduction target, a target of expanding the EU’s share of renewable energy to at least 27 per cent and a non-binding energy efficiency target of 27 per cent (European Council, 2014).

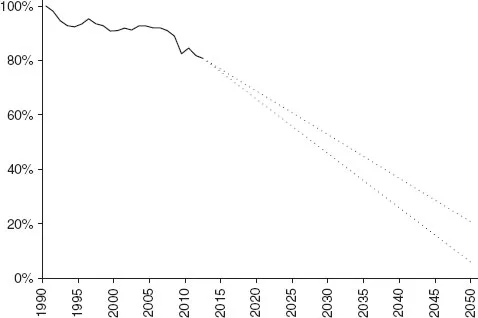

While any increase in ambition constitutes a step in the right direction, whether the proposed targets are sufficiently ambitious to move the EU towards decarbonization is a matter of debate (see Figure 1.3). Structural change needs to be initiated early on, since delays will make later changes more difficult (Neuhoff et al., 2014). In this respect, especially the targets for renewable energy and energy efficiency to 2030 have been criticised as insufficient.1 At the same time, the EU’s 2030 targets still are nominally the most far-reaching among the major international players.

Figure 1.2 Progress towards 2020 renewable and energy efficiency targets in the EU-28

Note: Actual figures from 2004 (renewables) and 2005 (energy efficiency) to 2012. Share of renewable energy measured as a percentage share of final energy consumption per year. Energy efficiency improvements measured against baseline of 2005 and the business-as-usual forecast for final energy consumption to 2020. Linear trajectories to 2020 targets from 2012.

Source: Eurostat data, ec.europa.eu/Eurostat, date accessed 18 November 2014.

Climate policy development in the EU since the late 2000s has occurred against the backdrop of a much changed and changing internal and external political context. The financial and economic crises from 2008 onwards have weakened the political priority accorded to climate policy, as have the political crises, such as in the Ukraine and the Middle East (Syria, Iraq, Palestine), and the Ebola crisis in Western Africa in 2014. The growing internal divergence of preferences, as most clearly visible from consistent Polish opposition to EU climate policy initiatives, was increasingly manifested as a major impediment to EU policy development. In contrast, by 2014, the Paris Climate Summit, scheduled for the end of 2015, where the conclusion of a new international climate agreement is expected, started to cast its shadow and arguably contributed to the agreement reached within the European Council in October 2014 (see above). Different to the Copenhagen Summit in 2009, the EU has not worked towards translating its targets into EU law prior to the 2015 Paris conference.

Figure 1.3 EU-28 GHG emission trajectory to reach reduction of 80–95 per cent by 2050

Note: Actual figures to 2012, linear trajectories to 2050.

Source: Own calculations based on EEA GHG data viewer (www.eea.europa.eu, date accessed 10 November 2014).

2. To 2050: Long-term policy planning

Soon after the adoption of the climate and energy package for 2020, the European Council, in October 2009, stipulated an ‘EU objective … to reduce emissions by 80–95% by 2050 compared to 1990 levels’ (European Council, 2009, para. 7). This long-term vision remains a political objective, without binding policy measures to implement it. It can also be argued that it does not represent a consensual and unconditional commitment and/or that it is politically over-ambitious or even unrealistic (Geden & Fischer, 2014). However, it is and remains in line with scientific estimates of the effort required to combat climate change. Even without consensual political blessing, the 2050 decarbonization objective provides a suitable benchmark for assessing the state and progress of EU climate policy.

On the basis of the aforementioned European Council conclusions, we furthermore assume, for the analysis in this volume, that there is a high level of political commitment to decarbonization in the EU.2 This assumption seems to be in line with a number of roadmaps published by the European Commission in 2011 laying out pathways for achieving the 2050 decarbonization objective, including a ‘Roadmap for Moving to a Competitive Low Carbon Economy in 2050’ (European Commission, 2011b), the ‘Energy Roadmap 2050’ (European Commission, 2011a) and the ‘Roadmap to a Single European Transport Area – Towards a Competitive and Resource Efficient Transport System’ (European Commission, 2011d). To achieve the overarching 2050 goal of reducing GHG emissions in the EU by 80–95 per cent, the energy sector is expected to reduce its emissions to close to zero by 2050, and the transport sector by at least 60 per cent.

Besides the European Commission’s roadmaps, various other research institutions and organizations have developed their own visions of how to reach the 2050 objective (see, for example, ECF, 2010; EREC & Greenpeace, 2010; EREC, 2010; EWEA, 2011; Heaps et al., 2009; PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2010; Shell International BV, 2008; WWF, 2011). While the various scenarios and roadmaps have differing assumptions and starting points, they aim to achieve at least an 80 per cent reduction in GHG emissions by 2050. The diversity among the scenarios stems from the choice of technology used to achieve the objective and from the various cost and public acceptance estimates inherent in these choices.

Carrying out a clear comparison among the many scenarios and roadmaps available is complex. The diversity of assumptions, aims and starting points of the scenarios means a comprehensive comparison based on clear points of reference is all but impossible. While some scenarios focus on the energy sector, others combine transport, agriculture, buildings and industry. Some scenarios explicitly provide absolute figures for their findings, but others rely on percentage point improvements. Wh...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Series Editor’s Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- List of Acronyms and Abbreviations

- 1. Decarbonization in the EU: Setting the Scene

- 2. The EU Internal Energy Market and Decarbonization

- 3. The Power Sector: Pioneer and Workhorse of Decarbonization

- 4. Electricity Grids: No Decarbonization without Infrastructure

- 5. Decarbonizing Industry in the EU: Climate, Trade and Industrial Policy Strategies

- 6. Transport: Addicted to Oil

- 7. Buildings: Good Intentions Unfulfilled

- 8. The Geopolitics of the EU’s Decarbonization Strategy: A Bird’s Eye Perspective

- 9. Decarbonization and EU Relations with the Caspian Sea Region

- 10. Evolutions and Revolutions in EU–Russia Energy Relations

- 11. EU-Norway Energy Relations towards 2050: From Fossil Fuels to Low-Carbon Opportunities?

- 12. Conclusions: Lessons Learned

- Index