eBook - ePub

Contemporary Issues in Macroeconomics

Lessons from The Crisis and Beyond

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Contemporary Issues in Macroeconomics

Lessons from The Crisis and Beyond

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In this edited collection, Joseph Stiglitz and Martin Guzman present a series of studies on contemporary macroeconomic issues. The book discusses a set of key lessons for macroeconomic theory following the recent global financial crisis and explores unconventional monetary policy in a post-crisis world.This volume is divided into five parts. The introduction includes keynote speeches by the Governors of the Bank of Japan and Central Bank of Jordan. Part one focuses on macroeconomic theory for understanding macroeconomic fluctuations and crises. Part two addresses the issue of the measurement of wealth. Part three discusses macroeconomic policies in times of crises. Finally, part four focuses on central banking and monetary policy.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Contemporary Issues in Macroeconomics by Joseph E. Stiglitz, Joseph E. Stiglitz,Kenneth A. Loparo, Joseph E. Stiglitz, Martin Guzman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Negocios y empresa & Negocios internacionales. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Negocios y empresaSubtopic

Negocios internacionalesPart I

Macroeconomic Theory for Understanding Fluctuations and Crises

3

A Theory of Pseudo-Wealth1

Martin M. Guzman

Columbia University

Joseph E. Stiglitz

Columbia University

3.1 Introduction

Recent events in the US and Europe have witnessed the limitations of conventional macroeconomic models to predict and explain large economic recessions and crises, and to provide guidance for policies that attempt to resolve them.

This chapter describes an agenda (that includes Stiglitz (2015), Guzman and Stiglitz (2014, 2015) that addresses two important puzzles faced by conventional macro models. Firstly, they are incapable of explaining situations in which there are large changes in the state of the economy with no commensurate changes in the state variables that describe it. Secondly, they cannot explain situations that involve persistent underutilization of the factors of production of the economy, a typical feature of crisis times.

These issues are not simply theoretical curiosities, but they have important implications for policy guidance. A model that cannot account for the persistent subutilization of factors of production will overestimate the speed of recovery from a crisis (a typical feature of the Fed forecasting models, and of IMF models as well2).

The key premise of our theory is that individuals may have differences in beliefs, and these differences can be economically exploited through markets. We assume there exists a market for bets that makes it possible. The betting model can be thought of as a metaphor that depicts a general situation in which trade leads to expected gains from differences in priors. In equilibrium, agents will engage in betting that leverages the side of the distribution of beliefs that each of them perceives as relatively more likely. Because each agent believes that, on average, he is going to win, the betting leads to a perception of a higher aggregate wealth – wealth that is not consistent with the societal feasibility locus; and this has implications on agents’ economic decisions. The “excess” wealth is what we define as pseudo-wealth. If those differences in beliefs disappear or cannot be exploited anymore (due, for example, to a shock to priors that eliminates any initial difference), pseudo-wealth will disappear, leading to adjustments in behavior that will amplify the initial decrease in expected wealth, with macroeconomic consequences.

The source of the disparity in beliefs is not important for our analysis. What is important is that we refer to events that rarely occur, over which it is not sensible to think that all the individuals share the same beliefs on the likelihood of their occurrence. As our theory wants to show that is possible to have changes in the state of the macroeconomy that go beyond changes in the state variables of the economy, we assume that the “rare event” does not affect any fundamental, that is, it has no initial effect on the real capacity of production of the economy – an event that we define as a sunspot. Our theory shows that the destruction of pseudo-wealth associated with its realization not only will lead to ex post suboptimal intertemporal paths of consumption, but it will also lead to destruction of real wealth.

An important result of our theory is that completing markets may lead to an economy that produces less in every period – but that may still be efficient according to the standard Pareto efficiency notion. This “contradiction” raises important questions in terms of welfare analysis. Should a market that only allows for speculation based on differences of beliefs, hence possibly increasing everyone’s ex ante expected utility but diminishing the level of output of the economy (and hence the level of ex post expected utility for a utilitarian social welfare function), be allowed? The answer will depend on the criteria we use for welfare analysis.

Finally, our theory highlights the important role of “natural” adjustments. After a shock that destroys aggregate pseudo-wealth, the natural adjustments of the economy lead to further reductions in expected wealth and lower aggregate demand, worsening the macroeconomic state. Our model shows that under some conditions the equilibrium with flexible wages is associated with lower production and aggregate labor income than the equilibrium with (somewhat) rigid wages. Wage rigidities could have distributive effects that positively affect on the demand for goods, reactivating the economy. This will generally be the case when demand effects are large – particularly when they dominate over substitution effects.

The rest of the chapter is organized as follows. Section 3.2 presents the main premises of our theory. Section 3.3 distinguishes two cases of analysis, an endowment economy and a production economy, and presents the main results. Section 3.4 analyzes the welfare implications of those results. Section 3.5 studies the implications of the “natural” adjustments that follow a shock to expected wealth, and delves into policy implications. Section 3.6 concludes the chapter.

3.2 Premises of the theory

The main premise of our theory is the existence of heterogeneous agents. This heterogeneity takes the form of different beliefs over the occurrence of a sunspot—a rare event that affects no state variables of the economy.

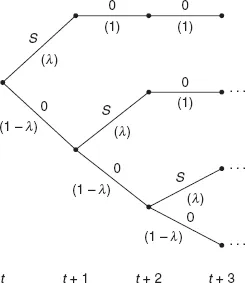

Before the sunspot occurs, there are two possible states: sunspot (S) or no sunspot (O). The true probability of occurrence of state S is λ. Once the sunspot occurs, it cannot occur ever again. Figure 3.1 describes the space of states.

The economy is populated by two forward-looking representative consumers (who in a version of the model are also workers), A and B, that differ in their beliefs over λ, such that λA > λB. Once the sunspot occurs, the difference in beliefs disappears, as everyone understands that the sunspot cannot occur again.

The difference in prior beliefs may be due to different reasons. It could arise due to differential access to information (which would be compatible with the assumption of rational expectations), or simply due to differences in the model agents use to analyze the world (which would be incompatible with the assumption of rational expectations). In both cases, posterior beliefs will be the same as prior beliefs. The reason is that as the sunspot occurs only once, there is nothing to learn from its non-occurrence.

The mechanisms we describe are consistent with a “rare event” that can actually transform the capacity of production of the economy (such as a structural transformation). We choose to assume that the event of interest takes the form of a sunspot because our goal is to show that it is possible, in equilibrium, to obtain changes in the state of the macro-economy with no commensurate changes in its fundamentals. The sunspot assumption simplifies the analysis: by leaving aside any possible change in the capacity of production of the economy, it is clear that all the changes in the state of the macro-economy are the consequence of changes in possibilities of exploiting differences in priors.

Figure 3.1 Space of states

The model features an infinitely lived small open economy with perfect access to international credit markets, where default is ruled out by assumption. Debt is denominated in tradable goods. Finance is provided by foreign risk-neutral investors whose opportunity cost is the risk-free interest rate (that we assume is constant).

There is a market for short-term bets over the realization of the sunspot. As consumer A is more optimistic than B about the likelihood of the sunspot, in equilibrium both agents will trade a bet that A wins if the sunspot occurs, while B wins if it doesn’t.

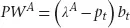

Let pt be the equilibrium price of the bet in period t, defined as the amount agent A pays to agent B for a bet that has a gross payoff of 1 in state S and 0 in state O. Each agent will expect a positive gain. Agent A expects to win 1 – pt with probability λA and pt with probability 1 – λA for each dollar (or good) she bets. Hence, the expected gain of agent A for betting in period t, a concept that we define as agent A’s pseudo-wealth, will be

where bt is the amount of betting in equilibrium.

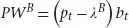

Similarly, agent B’s pseudo-wealth will be

In every period pseudo-wealth is destroyed but also created by new betting, until the period when the sunspot occurs, when no new pseudo-wealth can be created. Thus, the expected wealth of the society will decrease at that moment.

Consumers’ goal is to maximize the expected discounted value of utility, by choosing consumption of goods, betting, savings or borrowing, and in a version of the model, also leisure.

3.3 Results

Closing the model requires assumptions on the formation of output. We analyze two cases: an endowment economy where consumers receive and consume only a tradable good, and a production economy where consumers enjoy utility both from a tradable and a non-tradable good, and both goods can be produced in the domestic economy.

3.3.1 Endowment economy

We first assume that every agent receives a constant endowment of the tradable good in every period. Agents enjoy utility only from the consumption of that good. They decide consumption, borrowing, and betting in every period.

The creation of the market for bets has two effects: it creates pseudo-wealth, which increases consumption. But it also creates uncertainty, which increases precautionary savings. We are interested in analyzing situations in which the increase in expected wealth leads in equilibrium to increases in spending and aggregate demand. Thus, we constrain the family of permissible utility functions to the ones that guarantee that result. In Guzman and Stiglitz (2014), we solve the model for a utility function that features no precautionary savings, that is, the quadratic utility function.

Agents want to smooth out consumption over time. Given their expectations of future wealth (which include the pos...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Foreword

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction

- Keynote Addresses by Central Bank Governors

- Part I Macroeconomic Theory for Understanding Fluctuations and Crises

- Part II The Measurement of Wealth

- Part III Macroeconomic Policies in Unstable Times

- Part IV Central Banking and Monetary Policy

- Index