- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Reforming Pensions in Developing and Transition Countries

About this book

This book moves beyond technical studies of pension systems by addressing the political economy of pension reform in different contexts. It provides insights into key issues related to pension policy and its developmental implications, drawing on selected country studies in Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Latin America.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Reforming Pensions in Developing and Transition Countries: Trends, Debates and Impacts

Katja Hujo

Introduction

In the recent globalization period, pension systems have featured as one of the most dynamic areas of social policy reform and attracted widespread attention from scholars and policymakers. In the 1990s, after years of reform impasse, a number of industrialized countries (for example Germany, Italy and Sweden) introduced substantial pension reforms, while others have recently implemented reform amid widespread popular contestation (France, Greece). A set of developing and transition countries as diverse as Peru, Nigeria and Uzbekistan (Table 1.1) have radically reformed their public pension systems, usually involving a shift towards more market-based schemes through the introduction of privately administered pension funds based on individual capitalization. Other countries have been more cautious in their reform efforts or have postponed major reforms, as was the case in the Arab countries before the onset of the Arab Spring and with some of the newly emerging powers (the so-called BRICS – Brazil, Russia, India, China – and South Africa). Finally, we observe pension reforms with an emphasis on poverty reduction and social inclusion in such different contexts as Bolivia, Argentina and Chile, the latter being a country that had spearheaded the private pension model and is now looking for ways to strengthen the social functions of its old-age system.

Income protection during old age is a key social policy challenge in a world with a rapidly growing older population, coverage gaps of formal insurance programmes due to rising informality and strains put on informal protection mechanisms in a context of changing family patterns and increased migration. Against this backdrop, it is an issue of concern that the capacity of individuals to finance pensions is often constrained by their inability to save or contribute sufficiently to insurance programmes to earn a decent old-age income (Figure 1.1). At the same time, prospects for states to take up this responsibility are bleak, since pressures for fiscal austerity and states’ limited revenue mobilization capacity constrain the fiscal space of governments to provide income transfers to the elderly on a non-contributory basis.

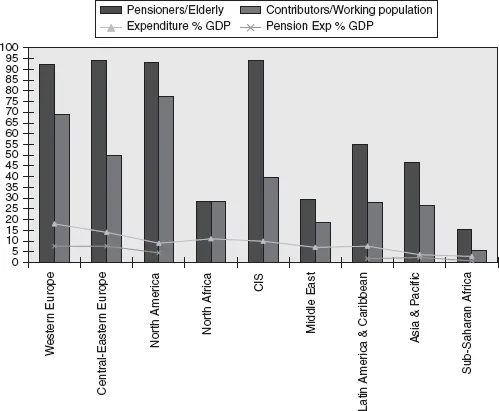

Notwithstanding these limitations, in most developed and many developing countries, pension schemes today are the most important social protection instruments for reducing old-age poverty in terms of their coverage and expenditure levels,1 while they are gaining importance in poorer countries that so far have relied primarily on informal safety nets. As Figure 1.1 shows, current coverage levels measured as the share of population above the legal retirement age in receipt of a pension are above or close to 90 per cent in Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS),2 around 50 per cent in Latin America and the Caribbean, around 30 per cent in Asia, North Africa and the Middle East, and 15 per cent in Sub-Saharan Africa. Future coverage levels in pension insurance are likely to be significantly lower, however, because of declining current shares of contributors to the working population. Old-age related public expenditure is highest in Europe, with Austria and Italy at the top of the list (around 12 per cent of gross domestic product, GDP), but with very low expenditure levels still prevailing in Sub-Saharan Africa and some Asian countries (Figure 1.1). Consequently, poverty in old age is still a challenge, especially but not exclusively for low-income countries with low spending and coverage rates, but also because pension benefits are often too small to lift the elderly above the poverty line.3

Since the international community agreed at the start of the new millennium to make poverty reduction its primary goal, the protective and redistributive function of pensions, in particular social pensions, has gained prominence in the run-up to 2015, when the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) are due to be achieved. Another milestone in the promotion of social security was the adoption of Recommendation No. 202 by the 2012 International Labour Conference on National Social Protection Floors (ILO 2012), a tripartite commitment of states and social partners to provide basic income guarantees and access to basic social services such as education and health for the entire population and across the lifecycle.4 Several international organizations (for example the World Bank, the Economic and Social Commission for Asia and Pacific, ESCAP, and others) have recently released social protection strategies including old-age protection to guide their global strategies as well as their operations at the country level.5

Figure 1.1 Coverage of pension programmes and public social security/old-age expenditure, regional averages

Notes: Coverage indicators:

Pensioners as per cent of population above legal retirement age (present coverage indicator)

Contributors as per cent of working age population (future coverage indicator).

Expenditure (excluding health) as per cent of GDP, regional averages (includes old age, survivors and disability pensions, work accidents, unemployment, family allowances).

Pension Expenditure as per cent of GDP, own calculations based on ILO 2010, table 26; no data for CIS and MENA, selected countries.

Source: ILO 2010: table 21, 25, 26, latest available year, selected countries, ILO online Global Databases on Social Security: http://www.social-protection.org/gimi/gess/ShowTheme.do?tid=10&ctx=0 (accessed 9 January 2014).

Pensions are not only interesting from the point of view of social protection: they also play a central role in economic development, via their impact on state budgets, the financial and monetary sector, aggregate demand, productivity and investment. Since the financial crisis of 2007–2008, the issue of contingent liabilities such as implicit pension debt (future obligations states have vis-à-vis current and future cohorts of pensioners) gained renewed attention in a context of sovereign debt crises, austerity policies and population ageing (European Commission 2012) – a concern that had already been articulated in the case of the Latin American pension privatizations in the 1990s (Hujo 2004; Datz 2012).

Furthermore, pension systems are constitutive pillars of a country’s welfare regime,6 whether they are based on citizenship/universal rights or labour rights, reflecting how societies recognize different types of paid and unpaid work, how they redistribute income and risk across gender, income groups and generations, and what role they attribute to public and private institutions in social protection.7

History shows that social protection schemes for the elderly are constantly evolving and adjusting to changing circumstances. This is because of the long time horizon under which programmes operate and the complex set of variables that influence the roles and functioning of pension systems. As Brooks (2009: 5) rightly observes, the question is not whether existing pension institutions change, but rather how they change: will they continue along the lines of a previously chosen system and maintain its underlying principles with only incremental changes being implemented, or will they undergo more fundamental reforms, changing the hitherto existing welfare paradigm? What explains the decision for or against a specific reform and what outcomes do reforms produce?

This book addresses the political economy of the most recent pension reforms in different contexts, the relative benefits in terms of social and economic development of various models for pension systems (for example, pay-as-you-go [PAYG] versus funded systems, decentralized models versus National Provident Funds, contributory versus non-contributory programmes) as well as challenges to managing and reforming pension systems in development and transition contexts. It aims to provide the reader with new evidence and debates related to pension policy and its developmental implications.

In order to prepare the common ground for the case studies compiled in this volume, which are briefly summarized at the end of this chapter, this introduction lays out some of the key concepts and debates around old-age protection and pension reform in a development and transition context. A comparative analysis of the findings of the different case studies as well as policy implications and lessons are discussed in the concluding chapter.

Pensions and Development

One of the aims the United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD) project on pensions, of which this volume is the main outcome, was to study the relationship between pension systems and economic development from a historical and contemporary perspective (Hujo and McClanahan 2009; UNRISD 2010). It aimed to shed light on the developmental functions of social policy, that is, social policy’s impact on growth and structural change, and the potential to combine development objectives with intrinsic values of social policy from a perspective of human rights and democracy (Mkandawire 2004: 1).8

Pension systems incorporate in an ideal way the multiple functions of social policy (UNRISD 2006).9 Pensions reflect the protective role of social policy by guaranteeing income security and preventing poverty during retirement or old age (or in cases of disability or death of the main earner), the productive role through accumulation of domestic savings (contributions) and demand stabilization (benefits), the redistributive role through risk and income redistribution between different groups of insured and across generations, and the reproductive role by reducing the financial and care burden associated with ageing, thereby improving gender equity and supporting households in their efforts to maintain a healthy and educated family and a functioning social fabric.10

For developing countries, where social security, and in particular pensions, are often deemed a luxury or a feature of industrialized welfare states, the productive function of social policy is of special importance. UNRISD (2010: ch. 5) identifies several channels through which pension schemes contribute positively to economic development (pp. 141–142):

•Pension programmes, in particular contributory occupational plans, provide incentives to both employees and employers to undertake long-term investments in skills, allowing firms to pursue a pattern of economic specialization based on the production of high-value-added goods, thus influencing the growth path of the economy.

•Pensions, in particular non-contributory schemes, guarantee social reproduction in households that are affected by contingencies (for example, maternity, sickness or unemployment) or poverty, potentially fostering local development through increased income security and diversification of assets and livelihoods.

•Income replacement programmes such as pension benefits (so-called auto...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables and Boxes

- Preface

- Notes on the Contributors

- List of Abbreviations and Acronyms

- Introduction

- 1 Reforming Pensions in Developing and Transition Countries: Trends, Debates and Impacts

- Part I Political Economy Issues in Pension Reform

- Part II Pension System and Reform in the BRICS

- Part III Bringing the State Back In

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Reforming Pensions in Developing and Transition Countries by K. Hujo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.