eBook - ePub

Delivering Sustainable Growth in Africa

African Farmers and Firms in a Changing World

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Delivering Sustainable Growth in Africa

African Farmers and Firms in a Changing World

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The purpose of this book is to fill the lack of micro evidences on a structural change of African producers. By collecting studies on single industries, we attempt to demonstrate firms' and farmers' responses to the recent economic trend such as growth of demand, emergence of FDI and improvement in infrastructure.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Delivering Sustainable Growth in Africa by Takahiro Fukunishi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economía & Finanzas públicas. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EconomíaSubtopic

Finanzas públicas1

Introduction: African Farmers and Firms in a Changing World

Takahiro Fukunishi

1.1 Purpose of the study

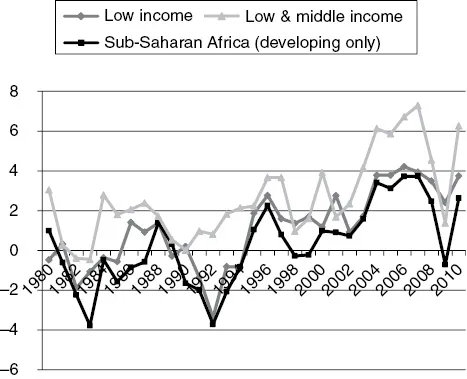

The economic situation in sub-Saharan Africa has undergone a recent transformation. After a long period of stagnation in the 1980s and 1990s, the 2000s have witnessed significant growth in GDP per capita. Although the growth rate of the region is lower than that of East Asia, currently it is significantly higher than that seen in previous decades (Figure 1.1). Arbache et al. (2008) confirm this acceleration of growth in the period following the mid-1990s, observed not only in the oil-exporting countries of sub-Saharan Africa but also across other low-income countries. The key factor in this improved economic performance is the upsurge in prices of commodities such as oil, minerals, and agricultural products – the primary exports of most African countries. Given the heavy reliance on the export of primary commodities, commodity price hikes significantly increased export earnings and, accordingly, terms of trade. The latter had witnessed a gradual decline in the 1980s and 1990s, showing improvement in the 2000s. Moreover, the upscaling of aid flows following the commencement of the Millennium Development Goals has been another factor. Enhanced commitment of the donor community increased the amount of aid flowing into Africa, thereby increasing the GDP through consumption of locally sourced products and services, such as those in the construction industry.

Figure 1.1 Growth rate of real GDP per capita (%)

Source: World Bank (2012).

However, the ability to sustain this improvement remains a great concern. If the rise of commodity prices is the only factor driving growth, it is unlikely that African economies will accomplish steady growth unless there is a persistent increase in commodity prices relative to the prices of other goods and services. Even if commodity prices continue to increase, the ‘resource curse’ problem, much discussed in the literature, may recur. Studies have indicated a significant negative impact of commodity dependence on economic growth, which is attributed to several factors such as large fluctuations in commodity prices, Dutch diseases and resource rent causing poor governance and conflicts (Sachs and Warner, 1995; Auty and Gelb, 2001; Collier and Hoeffler, 2004). The limitations of relying on natural resources is also obvious when considering the simple fact that the per-capita resource endowments in sub-Saharan Africa are much lower than those found in wealthy, resource-rich countries in the Middle East and North Africa. Oil exports from Nigeria, one of the most resource-rich countries in sub-Saharan Africa, amounted to only $488 per capita in 2010, while the high-income Gulf countries averaged $15,841.1 Only a few countries, such as Equatorial Guinea and Angola, seem to yield per-capita resources beyond the threshold of middle-income countries. Though price hikes and technological progress may encourage the discovery of new resources, they are unlikely to become large enough to lead the countries to middle-income status. Studies that examine development strategies for Africa stress the importance of diversifying industrial structures, particularly the development of manufacturing industries (Nissanke and Thorbecke, 2010; UNCTAD, 2008; Collier, 2007; Commission on Growth and Development, 2008; African Development Bank, 2007).

A key to the development of the non-resource sector is growth in productivity (Ndulu et al., 2007; Arbache et al., 2008; Commission on Growth and Development, 2008). It enhances the competitiveness of African products through reduction of costs or upgrading of product quality in export and domestic markets under a free trade regime. On the other hand, Bosworth and Collins (2003) in their growth-accounting study indicate that Africa’s stagnant economic performance until the 1990s can be primarily attributed to the slow growth – actually negative growth since the 1960s – of total factor productivity. This implies that African producers do not possess the experience to facilitate the consistent productivity improvements which can be observed in many developing countries. Therefore, overall productivity growth requires a structural change in Africa’s private sector, and more specifically in individual producers.

In fact, the increased inflow of foreign direct investment (FDI) is changing the performance of Africa’s non-resource sector. In conjunction with commodity revenue, increased foreign aid has augmented the purchasing power of domestic markets, which in turn has attracted an inflow of FDI in non-resource sectors. The most visible foreign investment is in the mobile phone industry, where foreign carriers cover almost all African countries. Moreover, in the retail sector, namely supermarket chains, the financial sector, and the construction industry, foreign investment, including those of African origin, are active to capture the growing African markets. In addition, preferential access to US and EU markets given to African countries has induced export-oriented FDI in the horticulture and apparel industries. Such foreign firms possess either newer technology, superior management or advanced marketing capacity to capture the export market, which cannot be secured by African firms. Their operations contribute to the productivity growth of the African private sector.

However, the industries in which foreign investors are interested remain limited. In addition, any decline in the current growth of domestic demand is likely to result in the discontinuation of investments made by foreign firms, similar to the period of the 1980s and 1990s. To achieve steady productivity growth, the role of local farmers and firms is indispensable, and in Africa, there are currently several factors that have the potential to bring about growth in local industries. Augmented domestic demand may realize increasing returns to scale in local industries, making local supply competitive. Slow yet steady improvements in the business environment are expected to encourage investment to facilitate productivity growth. In particular, investment in the communication and financial sectors has helped relieve bottlenecks from which African economies have long suffered. Moreover, as shown by previous experiences in developing countries, FDI plays an important role in the transfer of technology and knowledge to local industries. In the agricultural sector, contract farming provides opportunities to supply to new markets such as international, regional and domestic markets for smallholders.

Despite the strong emphasis on the recent growth of African economies, only a few studies have investigated its impact on African firms and farmers. The recent growth has been analyzed mainly from macroeconomic perspective (Arbache et al., 2008, Ndulu et al., 2007), while most microeconomic studies on African manufacturing firms do not focus on individual sectors; rather, they treat the manufacturing sector as a whole, abstracting subsector characteristics. In-depth sector or subsector studies are conducted based on the global value chain (GVC) approach particularly for the floriculture industry, which illustrate how African smallholders and entrepreneurs have changed with the growth of demand for African flowers. Given scarce empirical literature, the purpose of this book is to fill the lack of micro-evidence of structural changes in African producers. By collecting microeconomic sector studies, we demonstrate producer responses to ongoing changes in markets and the business environment. Since the market changes that industries experience differ by type, size and timing, their impacts on producers can be observed more clearly by focusing on a single industry. Using case studies, this book covers four industries that have experienced significant external changes, namely, export-oriented horticulture in Ghana and Kenya, construction in Burkina Faso, apparel manufacturing in Madagascar and cash-crop farming in Uganda. All chapters are based on field work conducted by the authors, and studies on Ghana, Burkina Faso, Madagascar and Uganda use original producer-level data collected by the authors.

Since the coverage of industries and countries in this book is limited, we do not draw a complete picture of changes that have taken place in sub-Saharan Africa, and instead demonstrate the potential and constraints of local producers under steady economic growth. The case studies that cover primary and secondary sectors and include industries that supply to export and local markets have substantial variations to represent the diverse experiences of African producers.

In the next section, this introductory chapter provides an overview of recent economic trends in Africa. Section 3 presents this book’s framework, which includes both theoretical implications and empirical evidence for the opportunities and constraints that local producers face. Section 4 briefly introduces the remaining chapters, followed by a summary of findings in the last section.

1.2 Africa’s recent economic growth

1.2.1 Overview

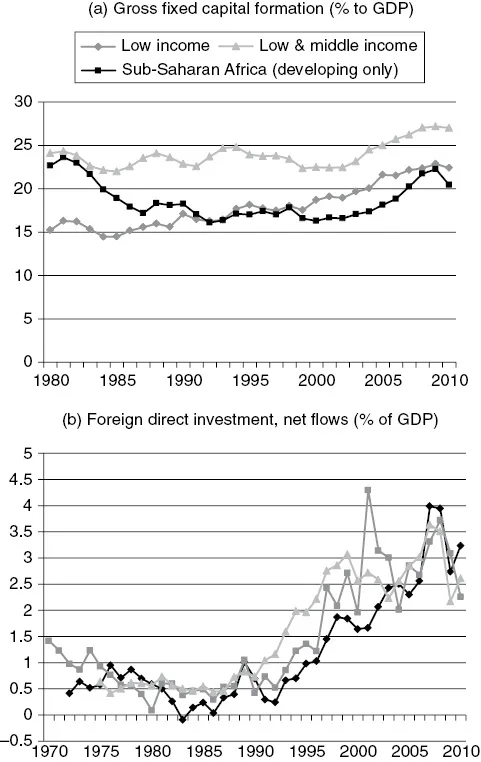

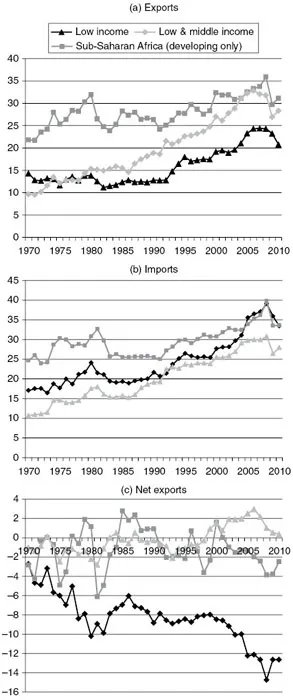

After two decades of stagnation, which amounted to negative average growth in real GDP per capita, growth rates finally turned positive in 2000 and were maintained until the recent financial crisis. The average annual growth rate during 2000–2008 was 2.2%, reaching 3.3% in 2004–2008. The growth rate of GDP per capita turned negative in 2009, but was followed by a prompt recovery in 2010 (Figure 1.1). GDP growth resulted from the growth of investment and exports at least until 2008. The share of investments in GDP increased by 5.5 percentage points and the share of exports rose by 3.5 percentage points during 2000–2010 (Figures 1.2a and 1.3a). In particular, FDI exhibited a sharp 2.2 times increase in the same period (three-year moving average). On the other hand, growth of investment and exports were partly offset by an increase in imports, which marked an 8.0 percentage point increase as a share of GDP from 2000 to 2008 (Figure 1.3b). Consequently, net exports dropped significantly in this period (Figure 1.3c). These data suggest that imported products and services account for a substantial increment in investment, and hence, local industries have not fully utilized the growth opportunity yet.

Since the financial crisis, both exports and investments have decreased in terms of GDP share. Nevertheless, the non-resource sector continues to grow, as shown in the following subsections.

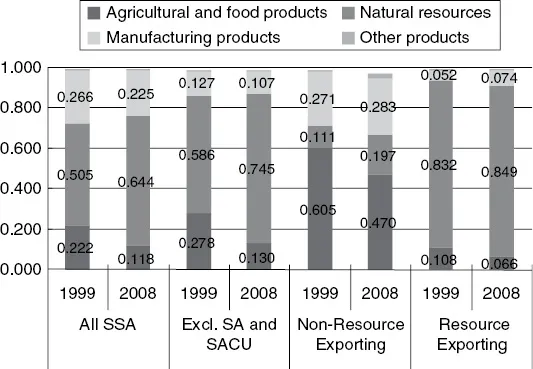

1.2.2 Exports

Export of natural resources has significantly increased since 2000. The share of natural resources in merchandise exports increased by 14.0 percentage points from 1999 to 2008 in Africa, excluding South Africa and Southern African Customs Union (SACU), the share amounting to 74.5% of total exports (Figure 1.4). To investigate changes of export structure by resource endowments, we separate African countries into non-resource and resource exporters; the latter are those countries whose resources have the lion’s share of total exports. This analysis shows the somewhat counterintuitive results that non-resource exporters increased resource exports by 8.6 percentage points, while there was no significant change in resource exports. This indicates that two forces contributed to the large increase in resource exports in Africa; non-resource exporters increased resource exports, and more significantly, the share of the resource exporters became larger among total African exports in 2008. It is noted that the share of manufacturing products did not decrease in either non-resource or resource exports despite the growth of commodity exports. Consequently, agricultural and food exports decreased, particularly in non-resource exports.

Figure 1.2 Share of investment (% of GDP)

Source: World Bank (2012).

Figure 1.3 Share of trade (% of GDP)

Source: World Bank (2012).

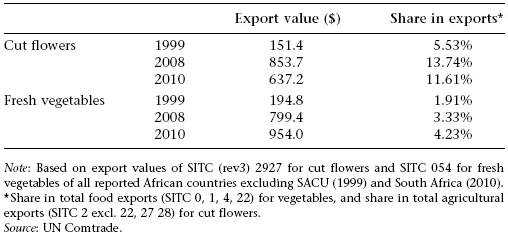

Macro-level observations, however, mask notable changes in sector or subsector levels. In agriculture, non-traditional products such as cut flowers and fresh vegetables have witnessed high growth. Because of improved access to international airports from rural areas in some African countries and advances in the logistics of transporting perishable products, supply to the EU market has been rapidly increasing. In African countries excluding South Africa, the average annual growth rate (nominal) of cut flower and fresh vegetable exports from 1999 to 2008 was 18.9% and 15.2%, respectively, and their respective export values grew 5.2 times and 4.1 times, respectively (Table 1.1). After the financial crisis, there was a decline in cut flower exports; however, vegetable exports continued to grow. Kenya, Ethiopia, Zimbabwe, and Tanzania have been recorded as top exporters. Fresh fruit exports are expanding in South Africa and Ghana. These perishable products yield higher value than traditional products.

Figure 1.4 Structure of merchandise exports (%)

Note: Products are grouped according to the following definition: Agricultural products and food: SITC 0, 1, 2, and 4 except 27 and 28; Natural resources: SITC 3, 27, 28, 667, 68, and 97; Manufacturing: SITC 5, 6, 7, and 8 excluding 667 and 68; Others: SITC 9 excluding 997.

Source: UN Comtrade.

Source: UN Comtrade.

Among manufacturing products, apparel showed significant growth of exports to US and EU markets. Apparel exports to the EU market began in Mauritius in the 1980s, followed by Madagascar in the 1990s. However, in 2000, the opening of duty-free access to the US market – African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) – boosted apparel exports to the US market from many African countries, with Lesotho, Kenya and Swaziland as the top exporters apart from Mauritius and Madagascar. During 1999–2004, export values increased by 73.2% and reached $28 billion (Figure 1.5). This represented remarkable development for African economies, which were previously characterized by several decades of stagnating manufacturing exports, in contrast to other developing regions. Apparel exports from Africa stagnated after 2005, when quotas on major apparel exporting countries were abolished, with the exception of Mauritius and Madagascar. Nevertheless, exports have recently recovered in Kenya and Lesotho, while in Madagascar, though exports to the US have fallen drastically because of suspension of duty-free access by the AGOA, exports to the EU market are steadily growing.

1.2.3 Investments

Table 1.1 Export value of cut flowers and fresh vegetables

Substantial investments are made in the resource-extraction sector, yet private and public investments are growing in other sectors as well. Infrastructure investment has grown significantly because of augmented aid flows from the OECD Development Assista...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables, Figures and Boxes

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- 1 Introduction: African Farmers and Firms in a Changing World

- 2 The Governance of Global Value Chains, Upgrading Processes and Agricultural Producers in Sub-Saharan Africa

- 3 The Fresh Pineapple Export Industry in Ghana: The Role of Smallholders in the High-Value Horticultural Supply Chain

- 4 The Beer Industry and Contract Farming in Uganda

- 5 The Export-Oriented Garment Industry in Madagascar: Implications of Foreign Direct Investment for the Local Economy

- 6 Local Construction Enterprises in Transition: Empirical Evidence from Burkina Faso (2004–2010)

- Index