![]()

1

Introduction

Banking market integration is accelerating in the Asia Pacific region, which has increased competition between domestic and foreign banks. Thus, the measurement of bank efficiency, competition, and liquidity creation in Asia Pacific economies is critical for both policy makers and bank managers to understand how these changes influence the domestic banking sector. These are important issues for policy makers because improved bank performance and competition should improve resource allocation, which will benefit society by intermediating more funds, providing a greater variety of products with better prices and higher service quality for clients, improving bank profitability, and achieving greater safety and soundness in the banking sector. These issues are also critical for bank managers because they can develop many different strategies, including rationalization, restructuring, consolidation, and so on, to improve performance in response to changes in their environment. This book consists of three empirical chapters addressing bank competition, efficiency, and liquidity creation in the Asia Pacific region.

Chapter 3 focuses on the impact of competition on financial stability. The analysis of the tradeoff between competition and financial stability has been at the center of academic and policy debate for over two decades, especially since the 2007–08 global financial crisis. Under the traditional competition-fragility view, banks cannot earn monopoly rents in competitive markets, which results in lower profits, capital ratios, and charter values. This makes banks less able to withstand demand- or supply-side shocks and encourages excessive risk-taking (Marcus, 1984). Alternatively, the competition-stability view suggests that competition leads to greater stability because in competitive banking markets, loan rates are lower, while Too-Big-To-Fail issues and safety net subsidies are smaller (Mishkin, 1999). An alternative view, presented by Martinez-Miera and Repullo (2010), suggests that bank competition and stability are linked in a non-linear manner, while Berger et al. (2009) argue that competition and concentration may coexist and can simultaneously induce stability or fragility. Recent studies on the causes of the credit crunch have highlighted deregulation and excessive competition as factors that led to the financial sector meltdowns in the US and UK. (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2011). Moreover, whether the relationship between banking competition and financial stability has been altered since the recent financial crisis is of interest to assess. While a substantial body of literature has emerged addressing this critical issue, the problem has been inadequately covered for banks operating across the Asia Pacific region. Against this backdrop, Chapter 3 of this book is devoted to investigating the competition-stability nexus utilizing cross-country data from 14 countries in the Asia Pacific region from 2003 to 2010.

Chapter 4 focuses on the impact of improved efficiency on shareholder value. Driven by technological innovation, structural deregulation, prudential reregulation, internationalization, and changes in corporate behavior, the global banking industry has been transformed over the last two decades (Berger et al., 2010). The global financial crisis of 2008–09 also accentuated these pressures and illustrated how poor bank performance influences capital allocation, company growth, and economic development by increasing capital and funding costs. Post-crisis, regulators tightened capital requirements (Bank for International Settlements (BIS), 2009; European Central Bank (ECB), 2012). In such an environment, many banks are finding it too costly and difficult to issue new capital. The only way banks can boost capital is to refrain from engaging in capital costly activities, such as reduce lending, sell or reduce investment banking, and other businesses (Economist, 2013). Shareholder value creation focuses on generating returns in excess of the cost of capital to create value for owners. In a world characterized by increasing capital costs, it may be difficult for banks (particularly from the developed world) to add value. The recent global financial crisis was the worst economic crisis for over 60 years, but most Asia Pacific countries weathered it quite successfully. Thus, this region offers a particularly interesting environment in which the relationship between bank efficiency and shareholder value can be investigated. However, the empirical literature on this issue is somewhat limited. To our knowledge, only one cross-country study in this field exists. To fill this knowledge gap, Chapter 4 examines the impact of bank efficiency on shareholder value for 14 Asia Pacific economies from 2003 to 2010.

Chapter 5 explores a two-way relationship between bank capital and liquidity creation. According to the modern theory of financial intermediation, liquidity creation is one of the two central roles played by banks in an economy. Banks create liquidity not only on the balance sheet by financing relatively long-term, illiquid assets with relatively short-term, liquid liabilities (Bryant, 1980), but also off the balance sheet by offering loan commitments and generating similar claims to liquid funds (Holmstrom and Tirole, 1998). Therefore, banks hold illiquid assets/loan commitments and provide liquidity to stimulate the rest of the economy. This liquidity creation function attracted significant attention because the recent global financial crisis demonstrated that illiquidity dramatically affects macroeconomic stability. As a result, Basel III introduced a global liquidity standard and strengthened the global capital framework to build a more resilient banking sector (BIS, 2011). There are two main bodies of literature on the relationship between bank capital and liquidity creation. One focuses on the causal link between bank capital and liquidity creation and develops two opposing hypotheses. The financial fragility crowding out hypothesis suggests that bank capital negatively influences liquidity creation because a fragile capital structure can be used as a disciplinary device to encourage banks to maximize liquidity creation (Diamond and Rajan, 2000, 2001), and higher capital ratios crowd out deposits and limit liquidity creation (Gorton and Winton, 2000). In contrast, the risk absorption hypothesis expects a positive effect because higher capital ratios encourage liquidity creation by improving bank risk-bearing ability (Bhattacharya and Thakor, 1993). The second body of literature considers the causal link between liquidity creation and bank capital and provides two opposing views. Matz and Neu (2007) argue that the more liquidity banks create, the higher their exposure to liquidity constraints. Consequently, banks may hold more capital to strengthen their solvency and improve their ability to raise external funds and withstand losses resulting from selling illiquid assets at fire sale prices. Thus, banks may raise their capital standards when they create more liquidity in the economy. We refer to this argument as the capital cushion hypothesis. An alternative view is that certain liquid liabilities may be perceived as stable funding sources, such as short-term deposits, and are expected to remain within the bank. Thus, when banks face a liquidity risk, they substitute these stable liabilities for capital. Hence, a negative effect of liquidity creation on bank capital is expected (Distinguin et al., 2013), which we call the liquidity substitution hypothesis. In the banking literature, only five empirical studies examine this issue in the US and Europe. Against this backdrop, Chapter 5 investigates the bi-causal relationship between liquidity creation and regulatory capital for 14 Asia Pacific economies from 2005 to 2010.

![]()

2

Development of the Asia Pacific Banking System

Banks have continuously dominated financial systems across the Asia Pacific region and played an important role in regional economic development. After experiencing rapid growth during the 1990s, Asia Pacific financial systems, especially banking systems, were hit hard by the 1997 Asian financial crisis. Regulators implemented a series of reforms to improve bank efficiency, competition, regulation, supervision, and profitability to enhance financial stability. These efforts have made Asia Pacific banking systems more resilient. These banks have weathered the global financial crisis much better than they did during the Asian financial crisis and better than banks in the U.S. and Europe. Basel III, which responded to the problems of sophisticated Western financial systems, have been widely implemented in Asia Pacific financial systems that are bank-dominated systems with relatively small capital markets and limited securitization. Tighter capital and liquidity requirements under Basel III may constrain bank lending and economic development. Therefore, the effectiveness of the Basel III changes is unclear.

2.1 The period before 1997

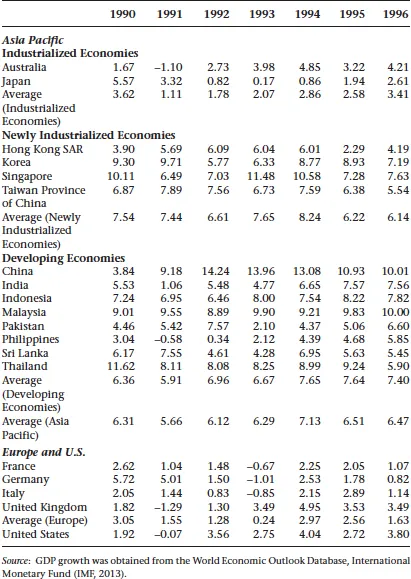

Before the 1997 Asian financial crisis, Asia Pacific economies experienced growth that was remarkably faster than in Europe and the U.S. (see Table 2.1). The average GDP growth rate during the 1990s in the Asia Pacific region was greater than 6%, which was much higher than growth rates in Europe (1.9%) and in the U.S. (2.67%). Specifically, newly industrialized and developing economies contributed to high rates of Asia Pacific GDP growth. High rates of economic growth may induce overly optimistic beliefs and expectations of persistent economic expansion, attract large capital inflows, and drive consumption and investment booms.

Table 2.1 GDP growth between 1990 and 1996 (%)

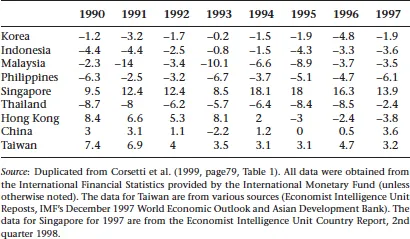

However, financial development alone cannot satisfy economic development strategies in the Asia Pacific region. The region’s financial systems have gradually revealed their severe weaknesses. On the one hand, the Asian financial system overborrowed a large amount of unhedged, short-term, foreign-currency funds. Lack of transparency and effective financial regulation and supervision, capital account liberalization and financial market deregulation in the region during the 1990s brought large, often undiscriminating, international capital flows into Asian financial sectors. Several Asian countries whose currencies collapsed in 1997 had experienced somewhat sizable current account deficits during the 1990s (see Table 2.2). Because bond and equity markets were relatively underdeveloped in this region, capital inflows financing the region’s large current account deficits were largely intermediated by local banking systems. Specifically, domestic banks borrowed large amounts of funds from foreign banks, apparently neglecting standards for sound risk assessment, and then lent to domestic firms. Therefore, a very large fraction of foreign debt accumulation was in the form of bank-related short-term, unhedged, foreign-currency denominated liabilities. By the end of 1996, shares of short-term liabilities above 50 percent of total liabilities were normal in the region, and the ratio of short-term external liabilities to foreign reserves – a widely used indicator of financial fragility – was above 100 percent in Korea, Indonesia, and Thailand (Corsetti et al., 1999).

Table 2.2 Current account based on national income account to GDP between 1990 and 1997 (%)

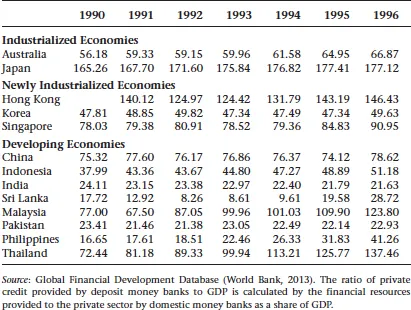

On the other hand, the Asian banking system overlent. Credit expansion was significant from 1990 to 1996 (see Table 2.3). The ratio of private credit provided by deposit money banks to GDP increased in most economies. Industrialized and newly industrialized economies boosted credit modestly. Among developing economies, India and Pakistan maintained relatively stable credit level, while the Philippines, Thailand, and Malaysia experienced the largest credit expansions, which were also the countries most affected by the Asian financial meltdown. The quality of loans can be measured by the ratio of non−performing loans to total loans, and Corestti et al. (1999) reported that the quality of loans was relatively lower in the Philippines (14%), China (14%), Thailand (13%), Indonesia (13%), Malaysia (10%), and Korea (8%) than in Singapore (4%), Hong Kong (3–4%), and Taiwan (3–4%) in 1996.

Table 2.3 Ratio of private credit provided by deposit money banks to GDP between 1990 and 1996 (%)

Hence, such overborrowing and overlending syndromes within undercapitalized banking systems produce fragile Asian banking systems. When the region’s local currencies experienced large depreciations against dollar or domestic firms experienced financial difficulties, domestic banks faced large short-term foreign-currency liabilities and non-performing domestic assets.

2.2 The period between 1997 and 1999

Asia’s spectacular economic growth was significantly affected by the Asian financial crisis. Most of Asia experienced output contractions, financial and nonfinancial business bankruptcies, and significant unemployment and poverty increases (IMF, 2007). Table 2.4 indicates that all economies in our sample were affected by the Asian financial crisis except Australia. The average rate of GDP growth in the Asia Pacific region reached its lowest level (−1.46%) in 1998, which was a much lower rate than in Europe or the U.S. Five countries were directly crisis−affected (Korea, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand), while two Asian financial centers (Hong Kong and Singapore) and the largest developed Asian country (Japan) were seriously hurt and experienced negative GDP growth during this period.

When the crisis struck Asian banking systems, their weaknesses (e.g., poor balance sheets, currency, and maturity mismatches) were exposed, which severely aggravated the downturn and led to widespread bank insolvencies. Table 2.5 suggests that the largest decline in the ratio of private credit provided by deposit ...