![]()

Part I

Introduction and Theoretical Discussion

![]()

1

The Emerging Powers and the Emerging World Order: Back to the Future?

Steen Fryba Christensen and Li Xing

Introduction: World order scenarios and ongoing transformations

Since the late 1990s, and especially in the new millennium, the world has been witnessing the dramatic rise of China, together with several large developing countries – Brazil, Russia, India – and many other countries that are labeled as the “Second World” (Khanna, 2012). In the current era of globalization and transnational capitalism, the ascendance of these emerging powers has redefined international relations (IR) and the international political economy (IPE) of upward mobility among the core, semi-periphery and periphery countries – a three-level hierarchy understanding of the world economic system as seen in world-system theory (Wallerstein, 1979, 2004). Furthermore, in concrete terms, the rise of new powers is affecting a number of global relationships – this includes those between great powers, the global South and developing countries – and new patterns of regionalization and regionalism are being generated.

Consensus exists today that “great transformations” are taking place in IR and IPE; these have reshaped the terrain and parameters of social, economic and political relations at both national and global levels. However, it is still being debated whether these transformations only represent some functional redistribution of comparative advantage within the existing world order, or whether they actually symbolize more serious structural changes – a paradigm shift – in which the institutions and regimes, as well as the norms and values grounded on the existing world order, need to be redefined. For the past five years, the editors of this book have been engaging in studies of the relationship between emerging powers and the existing world order, paying special attention to the extent to which emerging powers have exerted pressure on the existing international order in terms of both opportunities and constraints. We have also studied the extent to which both the existing hegemon and the emerging powers are intertwined in a constant process of shaping and reshaping the world order.

In recent years, the editors of this book have published extensively on this topic, focusing in particular on the rise of China (Li, 2010, 2014; Li and Christensen, 2012; Li and Farah, 2013; Christensen and Bernal-Meza, 2014). These publications are part of global academic research efforts to generate conceptual and theoretical frameworks for the interpretation and understanding of the transition and transformation processes taking place in the existing world order.

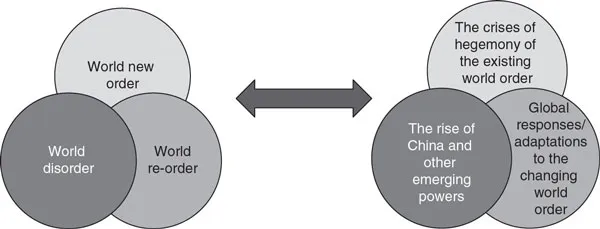

Currently, the world order is seen to be displaying changing characteristics in three different but overlapping ways: world disorder, world new order and world re-order.

World disorder: There are confrontations and clashes between existing and emerging powers due to disagreements and conflicts of interest, leading to the disruption of international regimes and of the established structure. The situation is vividly described by Schweller (2011, p. 287):

Its [the order] old architecture becoming creakier and more resistant to change. New rules and arrangements will be simply piled on top of old ones. And because there will be no locus of international authority to adjudicate among competing claims or to decide which rules, norms, and principles should predominate, international order will become increasingly scarce.

In Schweller’s heuristic formulation, it is “the age of entropy” in which “[i]nternational politics is transforming from a system anchored in predictable, and relatively constant, principles to a system that is, if not inherently unknowable, far more erratic, unsettled, and devoid of behavioral regularities” (Schweller, 2014).

World new order: The world is to be led by a new order; the argument is that disorder will prompt the existing and emerging powers to negotiate on new terms of relationship shaped by new norms and values, and new international law, leading to a redefined new world order. This is unlikely to happen because the world is composed of multiple and equally powerful players, i.e. states, transnational corporations, transnational networks and transnational interest groups. They are struggling to achieve their own goals and pursue their own interests in their own ways. None of these actors is able to shape the world order and impose its own agenda single-handedly.

Figure 1.1 The nexus between the scenarios of world orders and the processes of ongoing developments

World re-order: The existing order exhibits a capacity for resilience by responding to changing environments in which a transition from unipolarity to multipolarity is taking place. This order will undergo, willingly or unwillingly, a transformismo1 process in which new rising powers are accommodated into the existing structure, while the essential features of the existing order are maintained. This also implies that the hegemony that sustains the order is undergoing transition and transformation from a “unipolar-shaped” hegemony to one of “interdependence” (Figure 1.1).

While claiming that the world today is in a changing process of “reordering” – some scholars call this “a world order in transition” with a clear connotation of the “shift of balance of power” (Christensen and Bernal-Meza, 2014) – this chapter deems it to be necessary: first and foremost, to uncover the ongoing processes taking place in the world order that are bringing about functional and structural transitions/transformations within the existing world order. Currently, three parallel processes are taking place: the crises of the hegemony of the existing world order, the rise of China and other emerging powers, and global responses and adaptations to the changing world order.

Process 1: The crises of the hegemony of the existing world order

Historically, world orders, disorders or re-orders have always resulted from the disturbing dynamics unleashed by the rise of new powers and the resistance of established powers. The current global crisis has been interpreted from different perspectives and in different ways. Some academics regard it as the market’s natural and periodical pattern of ups and downs. Some scholars see it as a fundamental systemic crisis, i.e. a crisis of the existing model of accumulation, or a crisis of the core of the capitalist system (Christensen and Bernal-Meza, 2014). A dysfunctional international system is leading to chaos. It can be argued that the current international order is suffering crisis on four different but interconnected counts (Flockhart and Li, 2010): the state of multilateral cooperation, the growing need for multilateral cooperation, the uneven record of liberal foreign policies, and major shifts in the global balance of power.

Firstly, multilateral cooperation seems harder to achieve and sustain than liberals had anticipated, suggesting that the order is in a crisis of functionality, i.e. nation states and regional and international institutions are unable to deal with global crises in an effective and collective manner. The big question today is the extent to which the World Bank is relevant to the alleviation of global poverty, and the extent to which the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is still useful and effective in coping with global financial crises. The United Nations (UN) seems to be powerless in the face of veto powers. No international organization or national player is functional in resolving global security crises – the Syrian civil war, the Iranian and North Korean nuclear stalemates, the re-occupation of Iraq by terrorist groups, the crisis in the Ukraine, the territorial dispute in the East and Southeast China Sea.

Secondly, while multilateral cooperation is problematic, there is a growing need for it to meet an ever-expanding set of novel challenges in an increasingly globalized world. This is to suggest that world order is experiencing a crisis of scope; it is beyond the capacity of nation states and international institutions to resolve such a vast range of global problems, spanning from energy crisis to environmental degradation, from transnational organized crime to global terrorism, from territorial dispute to nuclear non-proliferation, and from civil wars to vast global inequalities.

Thirdly, the uneven record of liberal foreign policies in delivering a secure and just world order has challenged liberal values and prevented world order from living up to its perceived promises and expectations. As a result, it might be argued that world order is experiencing a crisis of legitimacy, i.e. a notion similar to Habermas’ “legitimation crisis”2 (1975). This implies that nation states have lost confidence in international institutions that they believe are just, benevolent and worthy of their support and adherence. Moreover, they have lost faith in the leadership and legitimacy of the hegemon and the core principal states’ ability to manage global affairs and to fulfill the proclaimed “end of history”.

Lastly, but not finally, major shifts are taking place in the global balance of power – removing it from the USA and Europe. World order is experiencing a crisis of authority, which is seen as a political struggle over the distribution of roles, rights and authority within the liberal world order (Ikenberry, 2012). This understanding of a “crisis of authority” is largely shared by international scholars (Flockhart and Dunne, 2013). The most obvious evidence is the fact that the rise of China and other emerging powers, including the Second World, has increased their decision-making power in the core international economic institutions, such as the World Bank and the IMF, and is challenging the hegemonic power exercised by the core states underpinning world order.

Debates on the continuity or discontinuity of “US hegemony” in world order continue. Some scholars draw a dark picture portraying a world ruled by non-Western countries such as Russia and China (Kagan and Kristol, 2000), claiming that without the USA, or without the future leadership of the USA, the world would not have peace, prosperity and liberalization (Kagan, 2012; Lieber, 2012). Other scholars maintain their endorsement of the continuity of US hegemony, seen from the perspectives of its leadership, economic wealth and mission of global management (Cumings, Hobsbawm and Chomsky, in Clark, 2009, p. 25). It is posited that, despite its relative decline, the USA remains the sole hegemony in the BRICS’ IR lexicon. Ian Clark disagrees with the concept and application of “hegemony” in connection with the USA. He strongly argues that hegemony is “a status bestowed by others, and rests on recognition by them” and is meant as “an institutionalized practice of special rights and responsibilities conferred on a state with the resources to lead” (Clark, 2009, p. 24). Seen from the perspective of “international society”, which views hegemony as a condition of legitimate leadership within international society, the idea of American hegemony is unachievable in contemporary international order (Buzan, 2008, 2011; Clark, 2009). However, some of the hardcore US elites still firmly believe that US hegemony will remain unchallenged and unchanged, as the former US national advisor Thomas Donilon declaims “We’re No. 1 (and We’re Going to Stay That Way)” (Donilon, 2014).

Nevertheless, globalization and transnational capitalism are not heading towards the consolidation of the US-led hegemony but, rather, towards diversification and differentiation in the sources and exercise of hegemony in 21st-century “decentralized globalism” (Buzan, 2011), depending on the economic sectors, political processes and/or social units in question. This development is regarded as a form of what sociological theorists call “functional differentiation”. This means that, in diverse ways, the definition and role of hegemon/hegemony have become differentiated and interdependent in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Process 2: The rise of China and other emerging powers

Since the beginning of the new millennium, the rise of China has become the focus of attention on the part of opinion- and decision-makers in the international system. The thesis of The End of History and the Last Man (Fukuyama, 1992) has been discarded, as has the assertion of “The Clash of Civilizations?” (Huntington, 1993), while the external impact of Chinese development and integration with the world economy as well as its global presence is being felt worldwide, contributing not only to many opportunities, but also many uncertainties:

• Its currency (the Chinese Yuan) has been the subject of dispute.

• Its trade has raised concerns for workers and firms in both developed and developing countries.

• Its hunger for energy and raw material has led to geo-political competition and commodity price increases.

• It has rivaled the USA and the rest of the developing countries as a destination for foreign direct investment, and the effects of its own overseas investments have begun to be felt across the world.

• Beijing’s policies on finance, currency, trade, security, environmental issues, resource management, food security, raw material and commodity/product prices are increasingly seen to be affecting the economy and lives of millions of people outside China’s borders, because China’s shifts in supply and demand cause changes in prices, leading to adjustment in other countries.

For many years, the rise of China has been raising global debate, particularly in the USA, about the “future of the West and the US” and the future of global order (Ikenberry, 2008, 2011).

In addition to China, a number of other emerging powers – such as the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) and the Second World (Khanna, 2008, 2012) – are changing the world’s political and economic landscapes and realities by introducing a new dynamic to global governance and by shaping new global economic and political relations.

According to a recent report by the IMF, the economies of Brazil, Russia, India and China now account for 20 percent of world economic output, i.e. a four-fold increase was seen in the first decade of the new millennium (Forbes, 2012). The BRICS and the Second World are now part of IR and IPE vocabularies, symbolizing a rising phenomenon of the changing world order in which that order can no longer be controlled and governed by the US-led postwar treaties. In this context, the term “BRICS” has been heuristically, and also sarcastically, applied by global media, not just as a new acronym but, rather, as metaphor for the changing global order, as seen in the title of a media article – “Building the New World Order BRIC by BRIC” (Roberts, 2011).

Process 3: Global responses and adaptations to the changing world order

Processes 1 and 2 indicate the fact that the global redistribution of power is inevitable. Implications of this ongoing redistribution of global power will be magnified by the fact that the rising powers are not only sharing their political and economic decision-making power with the West, they are also sharing their own political and economic norms of governance and capitalism. Seemingly, the emerging world order will not have one or two hegemonic power centers; rather, it will have a number of parallel centripetals competing for global/regional political, economic and cultural influence in a “war of position”3 under several groupings of states driven by certain common interests, i.e. the “historical bloc”.4

This situation is presenting both opportunities and constraints to various countries and regions. This particularly impacts countries in the global South, but also affects Northern countries or regions – these include Northern middle powers, one of which, although located in the Southern hemisphere, is Australia because of its level of development. Such countries and regions are compelled to adjust their international geopolitical and geo-economic strategies and policies to this new and complex changing world order. It also raises many questions. Are old alliances still maintained, or are new patterns of relationship forming? Is the new centrality of the “emerging economies” becoming vital and indispensable for some countri...