eBook - ePub

Community Resilience, Universities and Engaged Research for Today's World

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Community Resilience, Universities and Engaged Research for Today's World

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The increasing development of partnerships between universities and communities allows the research of academics to become engaged with those around them. This book highlights several case studies from a range of disciplines, such as psychology, social work and education to explore how these mutually beneficial relationships function.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Community Resilience, Universities and Engaged Research for Today's World by W. Madsen, L. Costigan, S. McNicol, W. Madsen,L. Costigan,S. McNicol in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Comparative Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Comparative Education1

Weaving Together the Strands of Engaged Research and Community Resilience

Wendy Madsen and Madonna Chesham

Abstract: Over the past few years, an increasing awareness of our vulnerabilities related to a surge of natural disasters has resulted in increased political and research attention on resilience, both personal and community. Academics, as members of communities, can contribute in a practical way to building community resilience through the process of engaged research methodologies. There is a natural synergy between the transformational and action-focused activities of engaged research and the social, economic and environmental capitals of community resilience. Woven together, engaged research can increase community resilience through collective problem solving, action, capacity building and sharing resources. In this chapter, Madsen and Chesham outline a framework that highlights how this can be accomplished.

Madsen, Wendy, Lynette Costigan, and Sarah McNicol, eds. Community Resilience, Universities and Engaged Research for Today’s World. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. DOI: 10.1057/9781137481054.0006.

Introduction

‘Engaged research’ and ‘community resilience’ each represent their own ambiguities and each in its own way has mobilised considerable political and academic attention in recent years. One may well question, then, the wisdom of bringing together two contested but popular terms as a way of focusing the research efforts of a group of diverse academics. While trying to avoid drilling down to the meaning of the last syllable in each of these concepts, we do need to provide an overview of what we mean by engaged research and community resilience and how we have used the messiness of each of these concepts to bring about that focus. This chapter provides that overview and in doing so, explains the framework that has been used by the researchers involved in the case studies outlined in the remainder of this book. This framework has started conversations amongst academics about what constitutes community resilience and has stimulated discussion about what engaged research entails, opening up other ways of seeing research activities. These conversations have not been completed, nor are they likely to be any time soon, as they represent some of the challenges associated with research and practice within academic institutions in the 21st century; institutions that are increasingly being drawn into the communities that support them.

It is no coincidence that universities have been likened to ivory towers: aloof and isolated from the hubris of humanity where research is about the generation of theory that is divorced from practice (McNiff, 2013; Strier, 2011). However, such imagery is no longer appropriate, or even desirable, if universities are going to fulfil their civic potential of being a part of the solutions to the problems facing communities (Gonzalez-Perez, MacLabhrainn, & McIlrath, 2007). Universities have three fundamental functions: to produce graduates who are capable of contributing to communities through their professional and personal activities; to undertake research that is ethical in its processes and purposes; and to represent and serve those who fund these activities, which in most cases in Australia and elsewhere, is the general public through the taxation system. As the 21st century progresses, there will be increasing pressure placed on universities to ensure all three of these functions are contributing in a meaningful way to resolving the issues of society associated with climate change, food security, capitalism and democracy among others. Many universities have embraced service learning as part of their engaged learning and teaching activities (Cress, Collier, & Reitenauer, 2013), but it is taking longer for institutions to do the same with their research activities (Harkavy & Hartley, 2012).

The issue of universities becoming centres of civic engagement is not something new. The promotion of ‘liberal arts’ in the 19th century related to developing graduates from universities who were well-rounded citizens as well as being skilled in their chosen professions (Gonzalez-Perez et al., 2007). Ira Harkavy and Matthew Hartley (2012, p. 19) point toward John Dewey’s arguments from the early 20th century related to ‘working to solve complex, real-world problems’ as the way to advancing knowledge and learning within individuals and institutions. Researchers and educationalists such as Kurt Lewin (1930s and 1940s), Paulo Freire (1960s and 1970s) and Orlando Fals-Borda (1980s and 1990s) have challenged the artificial distance between those real-world problems and the academy. Indeed, Jean McNiff (2013) suggests the increasing prevalence and acceptance of social sciences within the academy over the past three to four decades has helped dismantle the bastions of valueless objectivity and knowledge for knowledge sake. Universities are not separate entities from their communities. They operate within the social and political contexts of their times and their communities. As this chapter will argue, the more universities understand their knowledge generation as part of these social and political contexts, particularly through engaged research activities, the more both universities and communities will benefit.

Background

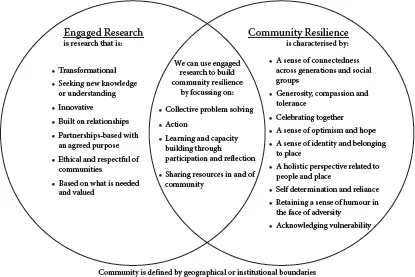

In February 2013, while Bundaberg and its surrounding districts were in the throes of recovering from a major flood event, a group of 12–15 academics from CQUniversity Bundaberg campus came together to consider how they could contribute to the recovery efforts and help build community resilience within this community. Some of the academics had not undertaken much research before, others were very experienced researchers. We ran two inductive workshops to develop a shared understanding of community resilience and engaged research. These workshops were based on the World Café process of small group conversations that are repeated until there is a sense of consensus; one workshop focused on community resilience and the other on engaged research. From these workshops, we devised a framework that summarised the points we considered important regarding each of these concepts and which highlighted where the concepts overlapped. It was in this shared space that we realised much of our efforts could be focused. The framework is outlined in Figure 1.1.

This framework was used by those researchers working with community groups on projects, as outlined in the case studies, to help bring a clearer focus to using these projects to contribute to building community resilience.

While the workshops provided a starting place for how engaged research could contribute to community resilience, we decided to compile a literature review to develop a richer understanding of each concept. One of the authors had been researching in the area of community resilience for some time and was able to draw on a wide range of literature collected as part of other projects. As such, much of the focus was on gathering literature related to engaged research. A library search was undertaken of the available databases and a small number of peer reviewed journal articles were found. However, it became evident that while engaged research is a term that is used by some, a multitude of terms encapsulate the concept of engaged research: community-based participatory research; participatory action research; collaborative research; and community-university partnership research. Each of these terms is associated with a considerable literature base. As a result, the literature review that forms the remainder of this chapter is in the form of a narrative and provides a broad sweep of the literature in order to highlight the interconnectivity between engaged research and community resilience (Baumeister & Leary, 1997). Each concept will be considered separately before bringing the threads together and exploring how engaged research can be used to bring researchers and community members together to collectively solve real-world problems, share resources, learn from each other and build capacity within our region.

FIGURE 1.1 Framework outlining how engaged research can increase community resilience

Engaged research

Engaged research is not a well-defined term within the literature, with a range of research activities being passed as ‘engaged’, from consultancies to equal partnerships, each with different levels of engagement, power differentials and philosophical bases (Nation, Bess, Voight, Perkins, & Juarez, 2011). Andrew Van de Ven (2007) outlines four main forms of engaged research: informed basic research; collaborative basic research; design and evaluation research; and action/intervention research. These forms vary according to the perspective of the researcher (external observer versus internal participant) and the purpose of the research (describing what is versus intervening to see what happens). Thus, ‘informed basic research’ describes, explains or predicts social phenomena in a way that resembles traditional social science research, but seeks some advice and feedback from key stakeholders. This could be researcher instigated or commissioned by an outside agency in the form of a consultancy. Where the purpose of such research is more evaluative or requires intervention designed studies, Van de Ven (2007) labelled this ‘design and evaluation research’. In both ‘informed basic research’ and ‘design and evaluation research’, the researcher maintains a traditional detached position in regards to the research and while there is input from stakeholders, there is a clear distance between the researcher and the stakeholders, their roles and who controls the research (normally power resides with the researcher).

Where there is considerably more stakeholder involvement in the design and conduct of the research but with the purpose of describing or explaining phenomena, this is known as ‘collaborative basic research’ (Van de Ven, 2007). ‘Action/intervention research’ also involves considerable shared decision making regarding the research design, data collection and analysis between researchers and stakeholders, but the purpose is more related to interventions that make a difference. In these studies, the researcher and the stakeholders have a much more collaborative relationship and the researcher is considered a partner in the research decision-making. Indeed, these types of engaged research try to minimise the distance between academic researchers and community members/stakeholders, often referring to all as co-researchers (Israel, Eng, Schulz, & Parker, 2013).

Engaged research that has taken a more consultative format has existed for a long time and provided both parties find this arrangement mutually beneficial, such arrangements are likely to continue to exist. This model has underpinned tenders and traditional externally-funded research conducted by university researchers throughout the 20th century and beyond. However, this model has also contributed to the image of universities as being detached from their communities, even if the research may in fact be related to ‘real-world’ issues. This model involves the notion of knowledge generation residing solely with academic researchers, while external stakeholders provide the funding and the brief. The academic researcher is responsible for the study design, how it is conducted, how the data are gathered and analysed and how and where the results are disseminated (Nicotera, Cutforth, Fretz, & Summers Thompson, 2011). This arrangement is very one-directional and any attempts by the stakeholders to have greater input has generally been interpreted by researchers as ‘interference’. The dominance of this model within universities is such that internal policies and procedures are based on this understanding of research which inadvertently devalues and erects barriers for other types of engaged research, as will be explored shortly.

Engaged research that consists of a more collaborative and partnership model between researchers and stakeholders/community members has been the subject of increasing interest in the literature and for university committees over the past decade, and as such, it is this form of engaged research that we focus on here. As more universities start to embrace the concept of university-community partnerships, there has been a shift in how communities can become more involved in not only the teaching and learning activities of universities, but also in research activities. Miles McNall and colleagues (2009) highlight that university-community engagement can be defined as a collaboration between higher education institutions and their local/regional/national/global communities for the mutual benefit of both in relation to the exchange of knowledge and resources. This definition emphasises mutuality, reciprocity and partnership as the foundations of university-community engagement, including engaged research, and involves a two-way direction of knowledge generation and responsibility (Weerts & Sandmann, 2010). While regional universities have been more likely to have community partnerships than metropolitan institutions, all universities need to make considerable social, cultural and political shifts in order to fully realise university-community partnerships that have transitioned from a one-way dissemination paradigm to a two-way constructivist model (Weerts & Sandmann, 2010).

Nicolas Buys and Samantha Bursnall (2007) have identified five steps in fostering university-community partnerships: engagement needs to be seen as a core value in the policies and practices of the university; academics need to see the benefits of pursuing partnerships with communities; formal marketing strategies that engage communities need to be adopted; rewards systems/incentives need to be implemented to encourage academics to engage with community partnerships; and more resources need to be devoted to encouraging authentic engagement. It is not enough for universities to write in their mission statements that they value engagement. As these five steps illustrate, considerable attention also needs to be directed towards encouraging staff to undertake engaged research and the structures within the university need to be such that this activity is adequately recognised and supported. At present, there is considerable evidence in the literature to suggest most universities are yet to have such recognition and support fully in place (MacLean, Warr, & Pyett, 2009; McNall et al., 2009; Nicotera et al., 2011; Savan, Flicker, Kolenda, & Mildenberger, 2009; Weerts & Sandmann, 2010; Wells et al., 2013).

The barriers to expanding community collaborative research are multi-level, complex and interdependent. From an individual academic’s perspective, undertaking such research requires a shift in civic consciousness, frequently changing one’s underlying assumptions about research, and learning additional skills and knowledge in order to participate in community and partnership development work (Harkavy & Hartley, 2012; McNiff, 2013; Savan et al., 2009). In addition, because establishing community partnerships is a very time consuming process as well as the time community-based projects take to carry out, academics need to have considerable time to be able to be involved (MacLean et al., 2009; Wells et al., 2013). Coupled with this, few external funding bodies are willing to support community-based research projects, not recognising them as ‘real’ research (McNall et al., 2009; Savan et al., 2009). These factors impact on the academic being able to seek funding to conduct research which has the effect of decreasing publications and thus, opportunities for promotion. As such, there is a perception (and frequently a reality) that community collaborative research is a ‘death-knell’ for an individual’s academic career. Such perceptions are not likely to help further any university’s mission of increasing engaged research.

Some of the solutions put forward include: having separate funding for establishing community partnerships to that being sought to support the actual project work, as the Wellesley Institute in Canada has done (Savan et al., 2009); universities providing internal funding to support partnership establishment (MacLean et al., 2009); and reviewing promotional criteria to incorporate or at least recognise the different requirements around community collaborative research (Nicotera et al., 2011; Savan et al., 2009).

Other issues relate to the quality of the relationships that are built between academics and community partners. Michele Allen and colleagues (2011) point out the partnerships between researchers and community members/agencies are impacted by: how prepared community partners are to be involved in research; how prepared and motivated academics are to adhere to community participatory research principles; the levels of trust between the partners; and how dynamic and responsive the university’s infrastructure is to deal with the logistics of community-based research. In a quantitative study of 58 community-university research partnerships related to Michigan University, Miles McNall and colleagues (2009) found most of the partners perceived their group dynamics to be effective, but identified a number of areas for improvement related to the sustainability of the partnerships and in some cases a lack of collaboration. They indicated that effective partnerships are associated with: increased focus on community issues, problems or needs; co-creation of knowledge; and shared power and resources. Many of these issues are addressed in the principles that underpin Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR). Barbara Israel and colleagues (2013) hold that CBPR is research that:

1acknowledges community as a unit of identity;

2builds on strengths and resources within the community;

3facilitates a collaborative, equitable partnership in all phases of research, involving an empowering and power-sharing process that attends to social inequities;

4fosters co-learning and capacity building among all partners;

5integrates and achieves a balance between knowledge generation and intervention for the mutual benefit of all partners;

6focuses on the local relevance of public health problems and on ecological perspectives that attend to the multiple...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 Weaving Together the Strands of Engaged Research and Community Resilience

- 2 Engaged Research in Action: Informing Sexual and Domestic Violence Practice and Prevention

- 3 Engaging with the Past: Reflecting on Resilience from Community Oral History Projects

- 4 Keeping Afloat after the Floods: Engaged Evaluation of a School-Based Arts Project to Promote Recovery

- 5 Making Space for Community Learning: Engaged Research with Teacher Aides in Disadvantaged Schools

- 6 Trailblazing and Extending Emergency Service Education: A Journey of Engaged Research and Partnership Building

- 7 Resilience of the Horticultural Community: Engaged Researchers Promoting Productivity and Profitability

- References

- Index