eBook - ePub

Economic and Policy Foundations for Growth in South East Europe

Remaking the Balkan Economy

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Economic and Policy Foundations for Growth in South East Europe

Remaking the Balkan Economy

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This volume argues that a renewed commitment to sound macroeconomic policies and structural reforms is needed for countries in South East Europe, or 'the Balkans' achieve to sustainable prosperity, along with enhanced support from the international community. New fiscal and financial architecture has valuable lessons for policymakers in SEE.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Economic and Policy Foundations for Growth in South East Europe by A. Bennett,R. Kincaid,P. Sanfey,M. Watson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Peace & Global Development. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Overview of Macroeconomic Developments

Abstract: This chapter reviews the achievements of SEE countries during the past quarter century. The period is analysed in terms of three distinct phases – the first (and sometimes painful) one of dismantlement and rebuilding, the second being the reward of the promised prosperity and a boom that got out of control, and the third is the economic hangover following the global financial crisis and the (continuing) problems in the euro area. It shows that the region needs to rebalance its output and production toward a greater reliance on foreign demand, and on domestic sources of savings to finance investment. The persistently high rate of unemployment in SEE has also put the spotlight on the region’s slow progress on structural reform.

Bennett, Adam, G. Russell Kincaid, Peter Sanfey and Max Watson. Economic and Policy Foundations for Growth in South East Europe: Remaking the Balkan Economy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. DOI: 10.1057/9781137488343.0008.

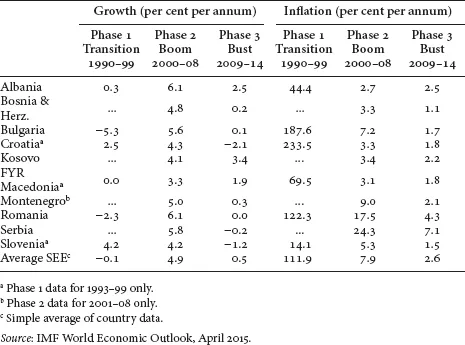

The economic development of South East Europe (SEE) since the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 can perhaps be divided into three distinct phases (see Table 1.1).1 The first phase comprised the early steps (and missteps) on the road to transition – the “valley of tears” as Jeffrey Sachs coined it.2 This period, from 1990 through the end of the decade, was initially characterised by the rocky road of output falls (from communist-era structures) and conflict (in the former Yugoslavia), price liberalisation and a burst of high inflation, privatisation of ownership and the rollback of the state, and the extension of market forces generally throughout the economy. But this early shock therapy and resulting disequilibrium were then followed by tentative economic recovery as the region’s economies began to find their feet again in the wake of the initial wave of reforms.

The second phase saw the region advance into the “sunlit uplands”, a partial mirage (as it turned out) where the fruits of transition seemed at last to ripen and then perhaps even to ferment. This was a period of rapid economic growth, driven by a combination of productivity improvements and rising domestic demand, while being financed by apparently limitless capital (mainly from Western Europe) and supported through increasing integration with the European Union (EU).3 It lasted from 2000 through the onset of the global financial crisis, which hit this region in the second half of 2008.4

TABLE 1.1 South East Europe – growth and inflation, 1990–2014

The third stage, which future economic historians may term the “wilderness years”, began with the region’s steep recession in 2009, as the subprime crisis and a sharp increase in financial risk aversion brought about a sudden stop in the capital inflows which had fuelled the previous decade’s heady growth. Nascent recovery in 2011 was cut short by the Euro-area crisis, and the region went back into recession in 2012. Unlike in phase 1, however, inflation has been subdued across the region and has even fallen below zero in several cases. The experience of this third phase, still ongoing as of early-2015, has forced a profound rethink of the region’s economic growth model.

Savings, investment and the balance of payments

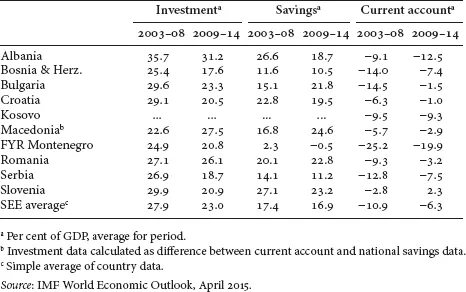

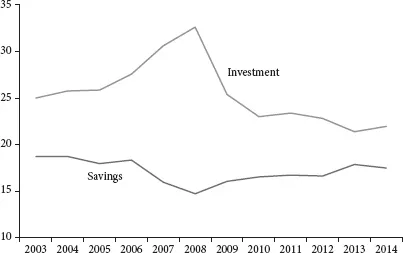

The growth surge during the second phase reflected a significant rise in investment. From an average of around 20 per cent of GDP during the latter half of the 1990s, the SEE investment ratio climbed steadily and peaked at well over 30 per cent just prior to the crisis (see Chart 1.1). As has proven the case elsewhere, investment rates in excess of 30 per cent of GDP are often associated with poor marginal returns and subsequent financial problems.5 The experience of SEE was to be no exception. As the first decade of this century progressed, investment in SEE was increasingly focused on real estate and on activities in the non-traded goods sector – servicing what was turning out to be a serious consumer boom fed by growing confidence and expected levels of earning potential that in the event were too optimistic. This high level of investment outstripped the region’s savings rate, resulting in a very large regional current account deficit, averaging more than 10 per cent of GDP in the period 2003–08 (see Table 1.2).

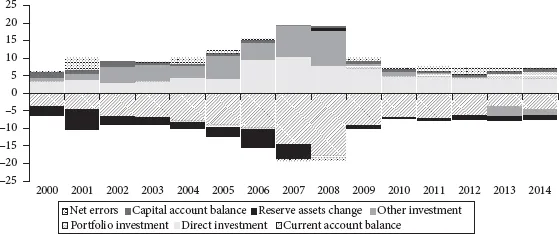

A large share of this current account deficit was financed by foreign direct investment (FDI). Chart 1.2 shows that FDI rose steadily in the first decade of the century, peaking at more than 10 per cent of GDP on average in 2007. Such financing tends to be more durable and less fickle, and brings with it foreign know-how. However, because much of this was going into non-productive sectors, it was doing little to regenerate export capacity.6 Instead, it was fuelling demand for local support services (building and other construction-related work) which was in turn bidding up wages and further adding to domestic overheating. By 2007, the investment boom far exceeded the supply of direct investment, and the extra demand for resources was met increasingly by commercial bank finance, mainly from banks in Western and Central Europe seeking superior yields. The situation was becoming very dangerous.

TABLE 1.2 South East Europe – investment, savings and the current account

CHART 1.1 South East Europe – savings and investment (percentage of GDP)

Note: Simple average of country ratios.

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook, April 2015.

CHART 1.2 South East Europe – balance of payments (per cent of GDP)

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook, April 2015.

The onset of the global financial crisis, which reached SEE in the second half of 2008 and peaked in 2009, triggered a sudden and dramatic increase in risk aversion around the world. Banks immediately began pulling funds back home from across borders. South East Europe was one of the first regions to be hit, as banks in Western and Central Europe began taking funds out of the region. Much of this credit had been used to finance mortgages (as it had, more infamously, in the USA) and the effect of this spigot being turned off on property prices in the region was immediate. At the same time, the collapse of the local real estate markets prompted a profound and negative reappraisal of other construction-related investment projects. Foreign direct investment inflows and investment activity in the region as a whole fell sharply. But there was still a gap with savings. As a result, the current account deficit narrowed in all countries, but was not eliminated.

The role of the international community and the Vienna I initiative

The situation in 2009–10 would have been worse but for two important international initiatives. The first of these was the so-called Vienna Initiative (or Vienna I).7 It was quickly recognised that the withdrawal of funds by banks from the region was a contagion process whereby no bank wanted to be the last one left exposed to a region in a downward spiral – a collapse that was itself in part being generated by those very withdrawals. The SEE region was especially exposed to this threat because a very large share of its banking system was foreign-owned. Officials at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), International Monetary Fund (IMF) and other institutions gathered together representatives of the main commercial banks involved and persuaded them to maintain their exposure to their subsidiaries, in exchange for commitments from the countries to which they were exposed to enter into arrangements with the IMF, as well as financial support for the affected banking groups from the EBRD and the European Investment Bank (EIB). The agreements formally covered Bosnia & Herzegovina, Hungary, Latvia, Romania and Serbia, all of whom entered into IMF programmes in 2009.8 In order to discourage banks satisfying their new-found cross-border risk aversion by withdrawing from other countries in the region instead, informal agreements with the banks involved were subsequently obtained to avoid this. The result was that a financial market rout was avoided, and net banking sector withdrawals all but stopped in the first quarter of 2009.9 Although the Vienna I initiative could not completely stop deleveraging from the region, it succeeded in slowing it to the point where it no longer posed a threat – at least through mid-2011 – especially for countries that agreed to IMF programmes.

The second important and complementary initiative was the mobilisation of lending by the international financial institutions (IFIs). At the forefront was the IMF, which stepped in with Stand-By Arrangements (SBAs) for Bosnia & Herzegovina, Romania and Serbia, worth the equivalent of US$ 11 billion in total in 2009. These programmes were followed by further programmes for other countries in the region, including an SBA for Kosovo in 2010, a Precautionary Credit Line for Macedonia in 2011, and an Extended (three-year) Arrangement for Albania in 2014, as well as follow-on programmes in some of those that received early crisis support. As Box 1.1 shows, the amounts involved were substantial, typically several hundred per cent of IMF “quota”, in contrast with pre-2009, when the arrangements were normally low-borrowing and often precautionary (i.e., the funds were available but not drawn). Other IFIs, notably the EBRD, EIB and World Bank also stepped up their support significantly, highlighting these institutions’ important roles as counter-balances against declining private investor appetite. In February 2009, these three institutions announced a Joint IFI Action Plan for Central Europe (CE) and South East Europe (SEE), to the tune of €24.5 billion over the period 2009–10, primarily to support banking systems in the region and encourage lending to the real economy. Final commitments exceeded this target by a considerable amount, reaching €33.2 billion.10 In parallel, all three institutions continued to provide support for critical infrastructure in the SEE region. A follow-up action plan was developed in late-2012 to help the region cope with the Euro-area crisis, again with joint commitments to CE & SEE exceeding €30 billion over the period 201...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 Overview of Macroeconomic Developments

- 2 Structural Reforms Is South East Europe Stuck?

- 3 Fiscal Policy and Fiscal Reform

- 4 Financial Policy Foundations for Growth in South East Europe

- 5 Financial Policy Challenges on the Horizon

- Bibliography

- Index