This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The book chronicles the Occupation Loan that was forcibly obtained by the Third Reich from the Greece in 1942-1944 and demonstrates why Greece's claim for the repayment of the loan is still valid. To overcome the absence of a normal debt agreement between the two countries, various assessments of its current value are presented and discussed.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Germany's War Debt to Greece by Nicos Christodoulakis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Macroeconomics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Infliction: Resource Expropriation as an Axis Policy

Abstract: During the Axis occupation in 1941–1944, Germany and Italy forced the Bank of Greece in 1942 to provide vast credit facilities for financing their armies, on top of an extensive expropriation of resources already imposed upon the country. Though some repayments did take place before the end of the war, the bulk of the Loan obtained by Germany remains outstanding up to date. Chapter 1 describes why the Loan was not written-off during the various concessions to German war reparations, thus today Greece is fully entitled to claim its repayment.

Christodoulakis, Nicos. Germany’s War Debt to Greece: A Burden Unsettled. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.DOI: 10.1057/9781137441959.0006.

Looting devours everything, including the looting army.

Napoleon, Military Maxims

A brief chronicle

Like all conquerors, the Axis powers of Italy, Germany and Bulgaria that occupied Greece in 1941 set in motion a plan of state revenue and public assets expropriation to pay for the occupation costs inflicted by their troops. Such a policy is formally allowed by the Hague Convention1 provided that the expenses of the administration of the occupied territory remain at pre-occupation levels as determined by the legitimate government and do not escalate to pillaging (Article 48). In order to restrict the extent of expropriation, the Agreement clearly forbids the confiscation of private property and acts of plunder and thievery (Articles 46, 47 and 53).

In practice, however, and in a clear violation of the Hague Convention, the Axis occupation forces imposed much more demanding expropriation tactics in most of the occupied countries, both in terms of the cash they took and of the resources they seized. In Greece, the Axis powers implemented a policy of extensive expropriation, confiscation and pillaging. Looting was common practice and included almost everything, from commodities and machinery to works of art, national treasures and private properties.

The intention was not limited to covering the subsistence of the occupation armies, but was part of a wider plan to support the Axis war effort even in faraway lands. Often, the expropriations were the result of the personal greed of officials, while in other cases the proceeds were used to buy-off local collaborators. A recent comprehensive study2 on Hitler’s looting policies reveals that a substantial part of the expropriated resources were transferred from “inferior” countries to Berlin, either to support German production or to finance the welfare policies granted by the Reich to the “superior” Aryan population. Similar policies and practices were applied in occupied Greece,3 disproving the early illusions that Hitler would respect the country because he admired its ancient history and monuments. In fact,

the Nazi occupation ... destroyed whatever it could and imposed a state of terror, violence and thievery. Nothing of the so-called indebtedness to the Greek heritage and civilization was acknowledged in action.4

A complete and accurate evaluation of the plunder is perhaps no longer possible and only ex post approaches can give us an idea of the real war damages suffered by Greece. Moreover, as time passes, full compensation of Greece becomes increasingly unlikely since only few survivors remain from the generations being personally hurt and the period of law suits is running out. All the more, nations often choose to re-prioritize their claims on war compensations as they take into account a multitude of pressures and limitations that prevail at present in the European Union. This implies that despite their historical and humanitarian significance, several Greek claims run the risk of falling into a negotiation limbo.

In contrast, the war debt commissioned through the forced Occupation Loan is not only possible to be measured with precision but also to avoid being “packed together” with other pending – and dithering – reparation claims. The loan was part of the Axis plan to seize monetary assets of the Greek state, while doing it in a way that would allow the occupiers to conceal it from being recorded either as conventional obligations of the occupied country or as a case of illegal and undocumented pillaging.

The Fiscal Conference of 1942

Italy and Germany had originally imposed that a large amount was to be paid by the collaborationist government for subsistence costs and administrative expenses of the occupation forces. The tide of war, however, posed additional and urgent financial challenges to the Axis allies. To address those needs, the Axis powers called a Fiscal Conference that took place in Rome in early 1942 and decided that they need additional funds. Since they could not justify further payments under the conventional occupation expenses, Italy and Germany demanded that a loan is disbursed from the Bank of Greece. Initially, the new occupation expenses were set at a maximum of Greek Drachmas (GRD) 1.5 billion, while any further credit would be debited to the Bank of Greece.5

Typically, there were two signatories to the Loan, but practically it is unlikely there was even the semblance of negotiation between the Axis powers and the collaborationist government. Already in the first months of the Occupation, Germany had appointed6 two Commissioners to the board of the Bank of Greece, one representing the Reich and the other Italy, who were in charge of the central bank’s monetary and banking policies. Under this arrangement, all payments to the Axis powers were authorized by the appointed Commissioners who obviously followed the orders of their masters.

Consequently, the Loan falls clearly in the category of resource expropriation, and it was not a voluntary credit facility; in the latter case, it would at least have included the pricing of risk as normally practiced by independent creditors. This point is very important in the attempt to determine the nature of the Greek claims, as it proves that Greece did not cooperate of its own accord with the Axis powers. The enforced character of the Loan was recently confirmed by no less authority than the Federal President of Germany. In a public speech in Athens, President Joachim Gauck admitted that “Greece had been forced to loan money to Berlin and had been economically exploited”,7 thus setting a moral and legal ground for its repayment (emphasis added). For this reason, the part of the Occupation Loan allocated to the Reich will be called, henceforth, “Forced Occupation Loan to Germany”, or FOLG for brevity.

1. Amendments: Shortly after the imposition of the Loan and the first disbursements took place, economic conditions deteriorated dramatically. On the one hand, the Axis powers were advancing in the North Africa Front and operational expenses of German troops increased immensely. At the same time inflation was rampant in Greece and occupation authorities demanded increasingly larger amounts of money to finance local needs. This quickly led to the amendment of the initial arrangement by raising the amounts of the required disbursements. A vicious cycle was set off by printing new money that further fueled hyperinflation and only ended after the country’s liberation.8 The nature of the transaction was also amended in three critical dimensions.

The first amendment, on 2 December 1942, raised the amount of occupation expenses to a maximum of eight billion GRD, adjusted for inflation, and if any further disbursements exceeding that limit would take the form of a loan.

The second amendment, on 18 May 1943, abolished the above ceiling and raised the reference inflation rate for adjusting the amounts received. Despite the fact that such a provision essentially meant that the real rate of return was zero, the amendment signified the conversion of the forced disbursements into something resembling a normal credit facility. In fact, this created a formal basis for estimating the value of the war debt, with a nominal return equal to inflation.

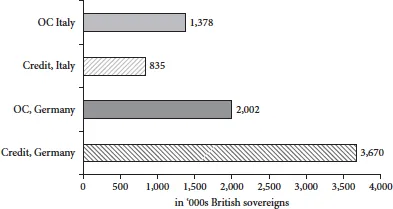

With the third amendment, on 25 October 1943, Germany took over the Italian share, as Rome had since capitulated. By the end of the occupation, Germany was by far the greater beneficiary of the additional disbursements compared to Italy. At the same time, Germany also undertook the obligation to expedite repayment. Before the end of the war, the Reich authorities had already made 19 payments, thus implying a formal credit basis of the – otherwise unorthodox – debt. The related data is presented in Figure 1.1.

2. Credit facilitation: According to the pertinent documents and accounts, the Axis occupation expenses were covered originally with an open-end credit by the Bank of Greece, in what we would call today ongoing credit facilitation. Normally, such loans are repaid in a short period of time that often overlaps, if required, with the extension of the line of credit. That this was the nature of the credit source extended to the Reich by the Bank of Greece is confirmed by the absence of any special clause that either specifies a rate of interest that would augment the amount of installments payable or would impose a surcharge on arrears.

FIGURE 1.1 Credits and Occupation Costs (OC)

Notes: (a) The figures are expressed in British sovereigns, based on the average monthly price at the Athens Stock Exchange. The data could have been expressed in GRD as well, but the resulting figures would be too unwieldy due to the enormous Greek hyperinflation. For the exchange rate of the Drachma against the British sovereign, see Table 4.1; (b) It is noticeable that if the same exchange rates are applied to the above amounts, they give somehow different results as compared to the Table of Expenses that was published in the same Governor’s Report. This seemingly paradox is due to the fact that, when a currency collapses, its value fluctuates wildly at irregular intervals. For this reason it is pointless and impractical to present figures in hyper-inflated GRD.

Source: Bank of Greece, 1947, Governor’s Report for the Years 1941–1946, Table ΙΑ, adapted by the author.

Only later, when the Reich started delaying repayments, did the German authorities accept to index the Loan to the rate of inflation based on the price levels of basic goods such as olive oil and bread. The composition of the basket of goods was meant to protect the real value of the payments from short-term variations in the cost of living. Essentially, this clause implied that inflation-indexing would be the only additional charge on the forced credit. In other words, the “real rate of in...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Infliction: Resource Expropriation as an Axis Policy

- 2 The Fruitless Claim: German Obstinacy and Greek Unpreparedness

- 3 The Impasse Continues: The Occupation Loan after German Reunification

- 4 The Valuation Mess: From Underestimating to the Overblown Claims

- 5 A Realistic Valuation: Alternative Estimates of the Loans Present Value

- 6 Negotiation: The Occupation Loan and the Greek Bailout

- Appendices

- References

- Index