This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Sharp in focus and succinct in analysis, this Pivot examines the latest developments and scholarly debates surrounding the sources of the European Union's crisis of legitimacy and possible solutions. It examines not only the financial and economic dimensions of the current crisis, but also those crises at the heart of the EU integration project.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Europe's Legitimacy Crisis by M. Longo,P. Murray in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Sociología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Ciencias socialesSubtopic

SociologíaPart I

Narrating the Past

In this part, we critically examine the ways in which crisis has become the default position of the European Union (EU). The current crisis is a culmination of institutional and governmental deficiencies, including inadequate architecture and weak policy responses to global, regional and domestic challenges. We are of the view that the EU has failed to adequately solve past crises, which have metastasised to now threaten its survival. The persistence of the current crisis draws attention to the inadequacy of past approaches, ranging from the treaty route and current policy prescriptions, to deal effectively with challenges. These are challenges of legitimacy, globalisation, economic stagnation, loss of competitiveness and related problems. Undoubtedly, the Euro crisis defies one-dimensional solutions, but the EU no longer seems able to solve problems and coordinate member state actions, despite being the repository of significant economic powers.

1

The EU Has Been Shaped by Crisis: Chronicle of a Crisis Foretold

Abstract: This chapter presents the case that the European Union (EU) has been shaped by crisis: the Empty Chair crisis in the 1960s, the Oil Crisis of the 1970s, the Eurosclerosis of the 1980s and the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. It further examines the background of crisis, institutional and symbolic, with a focus on the connections between the Euro crisis and significant past events such as the failure of the Constitutional Treaty, the ratification problems of the Treaty of Lisbon, the ongoing legitimacy crisis and EU enlargement. Viewed in historical context, the current crisis reinforces the expiration of both the permissive consensus and the acceptance of elite decision-making.

Longo, Michael and Philomena Murray. Europe’s Legitimacy Crisis: From Causes to Solutions. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. DOI: 10.1057/9781137436542.0006.

Introduction: the creation of the European Union out of crisis

This chapter examines the ways that the European Union (EU) has been created and shaped by crisis. The EU was founded on the basis of visions and dreams of a better life, of peace, of the promise of stability. It is the product of devastation after World War II. This was a political settlement of reconciliation and economic reconstruction. One of the EU’s fundamental achievements is the development of a ‘peace community’, which entailed reconciliation between former enemies, France and Germany. This peace community constitutes one of the EU’s core legitimating values (Murray, 2011). Reconciliation and peace were enunciated as the achievements of the EU in normative terms, just as economic development and prosperity became the core functional achievements. The EU was a security community in terms of geopolitical stability, political governance and economic strength.

It developed a narrative of learning from the bitter past of war, of peace and stability, including an experience that could be exported to other parts of the world (Forchtner and Kølvraa, 2012). Europe had learnt from its wars, and now its peace was a central element of the experience of stability and promise of prosperity for EU citizens.

However, Europe has changed dramatically. There is little or no narrative of peace or hope. It is perhaps ironic that the EU’s very success and leadership in some areas of policy, such as the single market, international trade negotiations, humanitarian assistance, development aid and climate change, have distracted it from important problems of governance, legitimacy and dealing with the concerns of its citizens. The current crisis is characterised by little vision that directly engages its citizens. It increasingly appears as a distant bureaucracy that represents more difficulties than solutions.

To an extent, the EU became engrossed in its agenda to be an economic competitor, a model and a power. Over time, its peace imperative was overtaken by its power imperative. It was accustomed to leadership in trade, aid and humanitarian assistance. It is active in norms entrepreneurship of its governance principles with both individual states and regional bodies. Now there is recognition that it is no longer a world leader in prosperity and economic growth, despite its trade strategy of promoting and protecting its interests and seeking alternatives to trade multilateralism when WTO negotiations on Doha broke down. When it comes to security and regional stability, Europe can no longer assume reliance on the United States in its own neighbourhood. The EU’s self-projection as the answer to problems and even as a model for other regions and states in the world has faded. Now it is increasingly seen as a model best avoided.

The EU is mired in crises of legitimacy, leadership, narrative, effectiveness and a lack of an effective Eurozone. Europeans struggle to discern the emblematic peace and prosperity project in the contemporary EU. They do not necessarily see themselves as belonging in the EU, and they do not envisage a future of solidarity and joint responsibility in union with other member states. In fact, a Eurobarometer qualitative study on the ‘Promise of the EU’, issued in September 2014, indicates that Europeans have witnessed a shift of narrative from peace to economic turmoil and that they believe the story of the EU is being written by the economically strongest European countries, meaning that the future of Europe will not be decided by all of its member states. Furthermore, Europeans from the six countries examined (Poland, Portugal, Italy, Denmark, Finland and Germany) have no enthusiasm for common EU taxation, and the idea of solidarity in terms of financial assistance for struggling member states finds little support in creditor countries (Eurobarometer, 2014c).

It can be expected that the EU will continue to harvest bitter returns from the crisis in the Eurozone. Rather than a glittering showpiece and innovative solution to regional economic governance, the Eurozone is seen as the EU’s Achilles’ heel. It is crippled by an accumulation of non-decisions – that is, decisions not to make decisions. Many challenges confronting the EU were not entirely resolved over many years.

The EU, fashioned and designed from war and devastation, has crisis at the heart of the European desire to create a new type of political project based on peace and stability. This response to crisis forms the foundation of its desire to expand its membership, to extend the reach of its policies and to influence multilateral agendas and outcomes. This has resulted in a multilevel governance system where the EU’s impact is experienced across government ministries, regions and civil society throughout its 28 member states, with attendant benefits and costs, all derived from an integration bargain at its origins, an uneasy coexistence between nationalism and Europeanism. This relationship between the EU and crisis has seen the emergence of an expectation, built up over time, that the EU would achieve even greater levels of integration (and prosperity) from dealing with its crises, one at a time. Some may still stubbornly cling to this view, but the weight of evidence suggests otherwise.

We consider that the EU is currently advancing an agenda that is different from its origins, yet which draws on its institutional genesis to seek solutions. We would suggest that the EU’s current problems are partly due to the distinctiveness of those very origins, with a teleological tone (Murray and Longo, 2015).

The early years of crisis, reconstruction and reconciliation

The EU was shaped by the crisis of war with its attendant guilt, demand for reconciliation and need for the reconstruction of the polities, societies and economies of Western Europe. However, it did not take long for national interests to reassert themselves, even if within the newly constructed European institutional architecture. And here began the tension – and phoney war (Peterson, 2001) – of national and European interests as played out often in zero-sum game narratives. Thus, the mid-1960s witnessed the Empty Chair crisis, when the French withdrew from active decision-making in the then European Communities (ECs). The EC – and EU – developed in a halting manner, as events such as the Empty Chair Crisis and the Luxembourg Compromise in 1966 illustrate. Already the narratives and justifications for cooperation were shifting, as economic imperatives took precedence over federalist and more overtly political principles (Murray, 2011).

The tensions of nationalism and EU-level decision-making were evident again less than a decade later, when member states responded individually to the oil crisis of 1973 without a commitment to a common energy policy or a common response to sanctions. The initial growth of the early decades was flattened by the Eurosclerosis of the 1980s. Europe’s economic growth was sluggish, and its economics were not competitive with the US and Japan. A comment made regarding this period of energy, economic and monetary crisis remains appropriate today, and it reinforces our argument that the EU history is one of crises and of a lack of coherent action in tackling these successive crises: ‘The time was not right for European enthusiasm and ambitious integration plans: instead it was a time for inward-looking action and protectionist reflexes’ (Bussière et al., 2014, p.15). The crises related to energy, unemployment, a lack of international economic competitiveness and of Eurosclerosis were to lead to the first attempts to create a Single European Market. The Single European Act (SEA) 1986 provided its institutional basis. The SEA came about after an intergovernmental conference was convened among the member states. It was also a response to a federalist desire for a constitutional basis to the European Economic Community (EEC), emanating from Altiero Spinelli and the European Parliament (EP) and culminating in a draft Treaty to bring about a European Union. Most member states balked from this initiative, although the resultant Dooge Committee drew up some proposals which drew in part on the Spinelli-inspired proposals and in turn led to the intergovernmental conference for the SEA. The Dooge Committee was established by the European Council in June 1984 to report on institutional changes required for the Treaties. It was chaired by Senator James Dooge, Ireland’s former minister for foreign affairs and recommended that an intergovernmental conference be convened in order to negotiate a draft treaty on European Union (p.23). The 1985 European Council in Milan adopted this proposal.

The 1970s crisis in the EC’s economy, lack of industrial competitiveness and a large measure of institutional inertia were to also reveal what amounted to a crisis of legitimacy in terms of power and competences – national power and institutional competences. National interests re-emerged forcefully, as was evident in the oil crises. They were manifest in the Council, where national representatives dominated the EU’s agenda. They were evident in the stalling of common EU policies. The problem was one of allocation of legitimate competences where it was evident that the Council had little political will to create an entity that was referred to in some of the narratives of federalist states and activists as ‘European Union’ or to redress the institutions’ democratic deficit. This was compounded by the frustration of the European Commission in seeking to create policies which had little chance of success. In a speech in Florence in 1978, Emilio Colombo (1978, p.5), the former president of the EP, stated that ‘Europe is facing a number of important decisions which it cannot afford to put off’. Yet these were not solved. In the 1970s and 1980s, there were repeated references by European leaders to institutional crisis and paralysis and the need for Treaty reform. Thus, the president of the European Commission was to state bluntly in 1983 to ‘[m]ake no mistake. What is at stake is the future of European Integration’ (Thorn, 1983).

A few months later, Thorn (1984, p.3) was to describe what was essentially a governance legitimacy crisis, that Europe was not governed:

This slowness to act, this reluctance to adapt, this dispersal of national efforts add up to a crying need – the need for government. Europe is not governed at the moment. The Commission proposes, Parliament urges, and no-one decides. This inability to take decisions, or at any rate to take them at the right time, is the Community’s worst failing. A good decision is usually one taken when circumstances call for action. The Council’s indecision has too often condemned the Community to doing too little, too late.

This was a case of national government working with EU governance where there was little sense of a common EU purpose and where both institutional and treaty reform were stalled and policy decisions were not being made, but were often delayed. The complex legislative decision-making processes of these decades rendered it difficult to be efficient, particularly the unanimity rule. More importantly, in the light of current crises, it meant that the EU did not have the resources of officials and legal competences to make and implement decisions at the EU level. The EU institutions with an integration commitment – the Commission and EP – had little power against national interests.

Expanding the EU’s membership

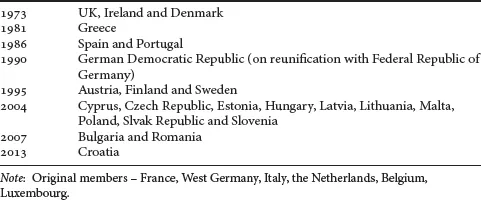

Although enlargements in the 1970s and 1980s were to present challenges to a Community designed for six similar member states, nevertheless they were regarded as success stories – the European integration process was attracting new members due to the advantages of membership and the ideal of democratic stability. In 1973, the UK, Ireland and Denmark joined the EC, followed by Greece in 1981 and by Spain and Portugal in 1986.

A fresh crisis was presented by the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, with a new type of Europe to deal with, no longer exclusively Western European and with distinctive objectives and concerns. This was to be followed by the exigencies of successive – and largely successful – enlargements. The enlargements were to change the character of the EU (and its predecessors) in membership, scope and impact, as well as narrative (Table 1.1).

Although enlargement was to be accompanied by a certain enlargement fatigue, many welcomed the end of the Cold War and this new Europe of many diverse nationalities. Enlargement presented new challenges not just of new members but also of new borders, new neighbours and new policies. The boundaries of Europe had been redrawn at the end of World War I and World War II. With the end of the Cold War, the collapse of communism and the breakup of Yugoslavia, the EC faced challenges in dealing with the desire of many countries to move closer to the EU as the Soviet Empire collapsed. In the period 2004–2007, the enlargement of the EU from 15 to 27 (and later 28, with Croatian accession in 2013) appeared to signify the end of the division of East and West. Yet enlargement in this first decade of the 21st century was also accompanied by considerable adaptation by both new and older member states. Resentment regarding new members was evident in many of the established member states. It appeared that the EU had expanded its membership too rapidly.

TABLE 1.1 EU enlargement and order of membership

The successive enlargements meant that the EU needed to develop a strategy towards the countries now on its boundaries – and so the Eastern Partnership – at the instigation of Poland and Sweden. In May 2009, this was launched to support stability in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine. Millions of euros of economic aid, technical expertise and security consultations were provided, as well as a number of bilateral agreements with the EU, which obliged these countries to commit to democracy, the rule of law and sound human rights policies.

Many Europeans were not only expressing a form of so-called enlargement fatigue in dealing with new member states but they also became weary of new treaties as the EU embarked on a frenetic program of reforms, as we show later.

Treaty fatigue

The SEA of 1986 effected the first amendment of the Rome Treaties since the EEC Treaties were signed in Rome in 1957. This was therefore the first major treaty reform in 30 years, coming after attempts to deal with institutional inertia and the dominance of national interests. Having done it once, successfully (the SEA was deemed highly effective in facilitating the creation of a single market), the EC soon embarked on a series of major treaty revisions that responded to new economic and geo-political realities following the fall of the Berlin Wall.

The SEA was followed by a pattern of intergovernmental conferences that resulted in several Treaties. A new Treaty, signed at Maastricht in 1992, the Treaty on European Union (TEU), renamed the EEC the EC to reflect its wider purposes. The Treaty of Amsterdam (1997) and the Treaty of Nice (2001) further amended the EC’s structure. There was an attempt to further reorganise the EC’s institutional structure under the Treaty Establishing a Constitution for Europe (Constitutional Treaty, 2004). The Constitutional Treaty (CT) was, however, dropped in favour of a slimmed down and renamed Treaty – the Treaty of Lisbon (2007) – which came into force in 2009. The EC Treaty was renamed the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU).

Although this did not constitute a crisis on a grand scale, with the abandonment of the CT, following the failed referendum outcomes in 2005 in France and the Netherlands, the EU lost the opportunity for greater democratic legitimation of its integration project, at least in the countries that had planned to subject the treaty to referendum. This de-alignment by the voters in two of the founding states of the EU registered a growing opposition to the EU, even if motivated by domestic concerns too. The failure of the CT halted any organic progress towards a form of political union that could have encompassed fiscal integration, not because the Constitution would have given shape to a form of state-like political union but rather because it would have represented an important benchmark from which further political integration could have sprung (Longo, 2006; Murray and Longo, 2015). The failure therefore thwarted the drive towards deeper integration and left only a deflated sense of treaty fatigue that has rendered the EU less relevant and less salient to many of its citizens. In a sense, that too marked a further nail in the coffin of the elitist project of European integration.

The crises, briefly examined earlier, were specific in length and nature. None resulted in a resolution that could be regarded as clear-cut. There were also some recurring critiques of the EU over time that fuelled both elements of Euroscepticism, on the one hand, and of a desire for the EU to be reformed from within its institutional architecture, on the other. The first is that the EU is over-bureaucratised and over-technocratic, a critique that has been evident since the 1960s. It constituted a reaction to the fact that the EU bargain for interstate cooperation involved heavy institutionalisation as a new pattern of bureaucratic behaviour and norms. The institutions quickly developed a regulatory framework that sought to codify its regulations and practices through legislation. In this sense, the EU became a formal and legal political...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- Part I Narrating the Past

- Part II Seeking a Future

- Bibliography

- A Guide to Further Reading and Useful Websites

- Index