This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

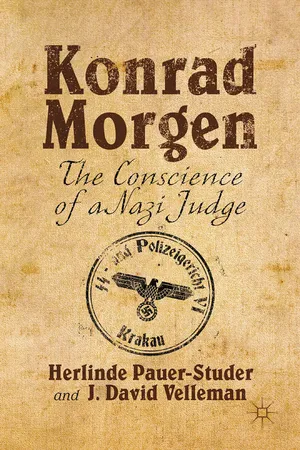

Konrad Morgen: The Conscience of a Nazi Judge is a moral biography of Georg Konrad Morgen, who prosecuted crimes committed by members of the SS in Nazi concentration camps and eventually came face-to-face with the system of industrialized murder at Auschwitz. His wartime papers and postwar testimonies yield a study in moral complexity.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Konrad Morgen by H. Pauer-Studer,J. Velleman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World War II. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ONE

INTRODUCTION

Transcript of The Auschwitz Trial

Twenty-fifth day of the proceedings, March 9, 1964

Examination of the witness Konrad Morgen1

My investigations in the concentration camp of Auschwitz were triggered by a small package in the military mail. It was a somewhat small packet, long rather than short, an ordinary box, which had probably come to the attention of the postal service because of its enormous weight, and the customs investigators had confiscated it because of its contents. It contained three lumps of gold. Gold was a currency subject to inspection, and that is how it came to be confiscated by the customs investigators. The sender was an SDG—that is, a medical assistant—in the concentration camp Auschwitz, and this packet was addressed to his wife. He came under the jurisdiction of the SS Police Court, and this confiscated mailing was directed to me, with a short notation; I think it was “for further action.”

As for the gold, it was high-caret dental gold that had been crudely smelted together. It was a very large lump, perhaps the size of two fists; the second was considerably smaller, the third less significant. But in any case, it was a matter of kilos. Before I dealt with it any further, I reflected on the matter. First, the audacity with which the as yet unknown perpetrator had proceeded—astounding. It seemed to be outright stupidity. But as I thought more about it, I thought that this interpretation underestimated the perpetrator. For after all, among hundreds of thousands of packages in the military post, there was a very small chance that this particular risky shipment would be confiscated and uncovered. But here it seemed to me that a refined barbarity and unscrupulous recklessness had predominated in the perpetrator— a trait that my later investigations in the concentration camp Auschwitz confirmed. That’s generally how things were carried out. My further reflection, however, sent no small shudder down my spine, since a kilogram of gold is 1,000 grams.

I knew that the dental wards of the concentration camps were tasked with collecting the gold that accumulated from the burning of bodies and sending it to the Reichsbank. And a gold filling is only a few grams. One thousand grams, or several thousand grams, thus represented the death of several thousand people. But not everyone had gold fillings in that impoverished time, only a fraction. And depending on whether one estimated that one twentieth or fiftieth or hundredth had gold in their mouths, one had to multiply the number, and so this confiscated shipment represented as it were twenty- or fifty- or a hundred-thousand bodies. [Pause] A shocking thought. But the literally incomprehensible thing was, that the perpetrator could have set aside such a considerable quantity undetected. And given that little notice was taken of the suspect’s exploit, I concluded, equally little notice might be taken if 50,000 or 100,000 people had disappeared and been turned to ash.

A natural cause of death wouldn’t have done it: those people must have been murdered.

It was from this standpoint that I first realized that this little-known Auschwitz, whose location cost me some trouble to find on a map, must have been one of the largest human-extermination facilities that the world had ever seen. [Pause] I could have dealt with the case of this confiscated gold shipment very easily. The pieces of evidence were conclusive. I could have had the perpetrator arrested and accused, and the matter would have been taken care of. But given the reflections that I have briefly delineated for you, I absolutely had to have a look for myself. So I went as quickly as I could to Auschwitz, in order to carry out inquiries on the spot.

One morning, then, I stood at the station in Auschwitz. One instinctively expects a facility in which the monstrous, the unspeakable, the unimaginable takes place, that the traces must somehow be visible, a peculiar atmosphere. So I stayed for a little while at the station, in order to see anything there. But Auschwitz was a small city with a very large transit and transfer station, a bit like Bebra. Trains were constantly going through, troop transports to the East, transports of the wounded coming back, coal trains, trains of ore, goods, and passengers too. The people who disembarked—the young ones gay, the older ones glum, worn out, as if it was the most mundane thing in the world. I also saw prisoner transports in striped uniforms. But they were leaving Auschwitz; none arrived.

So. You couldn’t miss the concentration camp, but from the outside it had the appearance that one was accustomed to from war-prisoner camps and other concentration camps: high walls, barbed wire, guard towers, guards walking back and forth. A gate, hustle and bustle of prisoners, but nothing noteworthy. I reported to the commandant, Standartenführer Höss, a somewhat stocky, taciturn, monosyllabic man with a stony face. I had already notified him by telegraph of my arrival and let him know that I had inquiries to make. He said something to the effect that they had been handed an enormously hard assignment, and not everyone had the character for it. He then asked curtly how I wanted to begin. I told him that I must first tour the whole camp. Before I began an investigation in a concentration camp, I inspected the camp overall, especially its main features. He looked quickly at the duty roster, made a phone call, and a Hauptsturmführer came. And he directed this man to drive me around the compound and show me everything I wanted to see. I started with the beginning of the end, namely, the ramp in Birkenau.

The ramp looked like any other ramp at a freight terminal. There was nothing special to discover there, no special precautions being taken. So I asked my guide how it went. He explained to me that the camp was notified by the station of a transport, usually of Jews, shortly before arrival, before it was due in Auschwitz. Then a guard unit was called out and they cordoned off the tracks and the ramp. Then the doors of the cars were opened, and the arrivees had to disembark and put down their luggage. Men and women had to form separate lines, and then, he explained, the rabbis were called for first. Rabbis and other Jewish notables were immediately separated out and brought into the camp, into a barrack that they had to themselves. I saw it later: it checked out. They were well cared-for, they didn’t have to work, they were expected to write letters and postcards all over the world from Auschwitz, as many as possible, so as to allay any suspicion that anything horrible was going on there.

Then a call went out for specialists needed in the camp—the camp was connected with large industrial concerns—and these people were picked out. Then the remainder were divided into those who were fit for work and those who weren’t. The ones who were fit for work marched on foot into the camp of Auschwitz, were duly recorded as prisoners, outfitted, divided into groups. The others had to take a seat in a lorry and went, without their names being taken, straight to Birkenau and into the gas chambers. My guide told me, with black humor, that if there was no time, or no doctor was present, or there were too many arrivees, they occasionally shortened the procedure by telling the arrivees in polite terms that the camp was several kilometers away, and whoever felt too sick or too weak or would find it uncomfortable to walk could make use of the transport facilities that the camp had provided. Then there was a stampede for the vehicles. And only those who didn’t join in could march into the camp, while the others had unwittingly opted for death. [Pause]

From the ramp we followed the path of the death cargoes to the camp Birkenau, which lay a few kilometers away. Outwardly there was again nothing remarkable to be seen: a large mesh-wire fence, a bit warped, with a guard. Behind it lay the so-called camp “Canada,” where the effects of the victims were searched, put in order, recycled. You could see a pile of burst-open suitcases from the previous transports, items of lingerie, briefcases, but also complete dentist’s equipment, cobbler’s equipment, medicine bags. Obviously the so-called evacuees really had the impression, as they had been told, that they were being resettled in the East and would find a new life there, and had therefore brought all the necessities with them. [Pause]

And in the back were the crematoria. They were one-story, gabled buildings that could just as well have been small workshops or work-sheds. Even the wide, massive smokestacks needn’t have attracted the attention of civilians, since they were very low, ending a bit higher than the roof. On the side where the lorries drove up, the ground was sloped, about the size of a schoolyard, spread with cinders [unintelligible]. They drove in in such a way that a bystander who saw the caravan of lorries could just tell that they had disappeared into a depression in the ground, without being able to tell where the transportees had been dropped off—here again one of those subtle but fundamentally primitive precautions that one repeatedly found, like a common thread running through the whole organization. [Pause] In the courtyard was what can only be called a pack of Jewish prisoners wearing the yellow star, with their kapo,2 who carried a long club, and they immediately surrounded us. They continually ran around in a circle, prepared for any order and snatching at every glance. And the thought ran through my mind: they acted just like a pack of sheep dogs. So I said that to my guide, who laughed and said, yes, that was their job. The condemned should at first be reassured by seeing their co-religionists. And this commando had instructions not to strike the arrivees. They should avoid anything that would cause an outbreak of panic. Rather, they should inspire a bit of anxiety and respect, but mainly just be there and lead or guide them where one wanted to have them.

In the back of the courtyard was a big gate that led into the so-called changing rooms, like the changing room of a gym. There were simple wooden benches with clothes racks, and each spot was clearly numbered and had a locker tag. And the victims were instructed to take note of their locker and hold on to their locker tag—all so as not to let them have the slightest suspicion until literally the last second, and to lead the condemned into the trap without a clue.

On the wall was a big arrow pointing to a corridor, and on it the terse words “To the showers” repeated in six or seven languages. They were told: you folks undress and you’ll be showered and disinfected. And on this corridor there were various chambers with no furnishings—cold, bare, a cement floor. What was noticeable and at first inexplicable was that there was a grated duct in the middle, reaching to the ceiling. At first I could think of no explanation for it, until I was told that gas—Zyklon B in crystalline form—was poured into this death chamber through an opening the ceiling. Until that moment the prisoner was clueless, and then of course it was too late. Across from the gas chambers were the lifts for the corpses, and these led to the second story, or, viewed from the other side, the ground floor. [Pause] The actual crematorium was a vast hall in which, on one side, was a long row of crematory ovens, with flattened floors, all exuding a matter-of-fact, neutral, technical, bland atmosphere. Everything was spick-and-span, and a few prisoners in mechanic’s outfits polished the armatures and contrived to look busy. Otherwise, it was completely quiet and empty.

Having seen these outer installations without any SS making an appearance, I was of course interested in meeting the SS personnel who managed the whole apparatus and kept it running. So I was allowed a brief glimpse into the so-called guardroom of the camp Birkenau, and here for the first time I received a real shock. As you know, in every army in the world a military guardroom is distinguished by a spartan simplicity. There’s a desk, a few notices hung up, a few cots for those who have been relieved, a desk and a telephone. But here it was different. It was a low, rather dim room, and a few colorful couches had been thrown together. And on these couches, lying picturesquely, were a few SS men, mostly below officer grade, drowsing with glassy eyes. I had the impression that they must have drunk a fair amount of alcohol the night before.

Instead of a desk there was a giant hotel stove, on which four or five young girls were baking potato pancakes. They were obviously Jewesses, very pretty, oriental beauties, full-busted, fiery eyes, wearing not prisoner’s uniforms but normal, even coquettish dresses. And they brought the potato pancakes to their pashas, who lay around on the couches and dozed, and asked them anxiously whether there was enough sugar on them, and fed them. [Pause] No one took any notice of me and my guide, though he was an officer. No one saluted, no one stirred. And I couldn’t believe my ears: These female prisoners and the SS, they called each other “du.” I could only give my guide a dumbfounded look. He just shrugged and said, “The men have a hard night behind them. They had to dispatch several transports.” I think he put it that way. That meant that during the night, while I stood riding on the train to Auschwitz, several thousand people, several trains’ full, had been gassed and turned to ash. And of these thousands of people, not the slightest bit of dust remained on the oven fittings. [Pause]

After I had seen everything there was to see in Birkenau, I made a tour of the camp. In quick succession: some well-chosen prisoners’ rooms or barracks, the cultural amenities that the camp even had, [pause] the sickbay. And then I of course had them bring me to the so-called bunker, and there I was shown—openly and most willingly—the so-called Black Wall, where the shootings took place. [Pause]

After I had looked over the camp—it had meanwhile become late afternoon— I went into action and had the whole SS crematorium commando fall in before their lockers, in their quarters, and I made a search. And as I had thought, various things came to light: gold rings, coins, chains, pearls, pretty much all the currencies of the world. Here small “souvenirs,” as the owner called them;...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Timeline

- Main Characters

- Map of the German Reich and Polish Territories, 1942

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The SS Man

- 3 The SS Judiciary

- 4 Criminals and Spies

- 5 The Criminal Character

- 6 The Issue of Race

- 7 From Cracow to Buchenwald

- 8 Karl Otto Koch

- 9 From Corruption to Murder

- 10 Partners in Crime

- 11 “Legal” Killing

- 12 The “Final Solution”: Conflicting Stories

- 13 Aktion Erntefest

- 14 Auschwitz

- 15 Adolf Eichmann

- 16 The Weimar Trials

- 17 Rudolf Höss and Eleonore Hodys

- 18 Out of the Fray

- 19 Postscript

- Appendix 1: Sample Documents

- Appendix 2: Photos

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index of Subjects

- Index of Names