eBook - ePub

International Perspectives on English Language Teacher Education

Innovations from the Field

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

International Perspectives on English Language Teacher Education

Innovations from the Field

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The chapters in this volume outline and discuss examples of teacher educators in diverse global contexts who have provided successful self-initiated innovations for their teacher learners. The collection suggests that a way forward for second language teacher preparation programs is through 'reflective practice as innovation'.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access International Perspectives on English Language Teacher Education by T. Farrell, T. Farrell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Teaching Languages. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Teaching Languages1

Second Language Teacher Education: A Reality Check

Thomas S.C. Farrell

Introduction

This introductory chapter is a state-of-the-art (SOA – of sorts) on second language teacher education (SLTE). However, it is not the usual type of SOA review (for a recent excellent review see Wright, 2010) one would normally read because I maintain that second language teacher education is in a state (i.e., a negative state) and so this chapter is more of a reality check for second language educators that we need to be doing something different. Part of the reason for the state we may be in is that we may have lost sight of whose needs teacher educators are addressing when preparing second language teachers: their own or their teacher learners’ needs? This is not an easy question to answer because there are many stakeholders involved within second language teacher education and each can have a different agenda than the other, but as you will see in this chapter I agree with Faez and Vaelo (2012) when they suggest that teacher preparation programmes should reconsider how programme content needs could be aligned more closely with the needs of novice teachers. As such, I also talk about what some teacher educators are attempting in order to prepare their teacher learners for the reality of what they will face in the classroom in their first year(s). Thus I also discuss the art in terms of self-initiated innovations that various teacher educators in different contexts have attempted to implement in order to compensate for the state we seem to be in. In addition, when I talk about “innovation” here and throughout the book I mean the process that has taken place in terms of the actions and steps various educators have taken to implement a particular innovation (Mann & Edge, 2013). As Mann and Edge (2013: 2) point out: “it is the realisation of an idea in action that constitutes genuine innovation.” I shall return to the idea of innovations and teacher learning in the final chapter.

The reality

First my reality: I was not adequately prepared to deal with the realities of teaching in a real context (Farrell, 2012). I clearly remember my first month as a newly qualified English language teacher in a university-affiliated language institute. In the third week of the semester the Director of Studies told me that she would be coming to observe my class. I prepared as usual and commenced my lesson following my plan. The lesson seemed to be going well but after about twenty minutes the Director suddenly stood up and, in a “You call yourself a teacher?” moment (Fanselow, 1987: 1), suggested that I was not doing the lesson correctly (I was doing a communicative activity in groups). She proceeded to take over the class for the remaining 25 minutes, drilling the students via teacher-led grammar activities. After class, she said to me, “That is how to do it!” and then she said not to worry as I would learn in time, and that “those new group techniques you were using will not work in this institute.” I remember how low I felt emotionally and professionally as I had been denigrated in front of my own students and how I felt like leaving the profession, thinking that maybe I was not suited to be a language teacher. Thank goodness that, at the very beginning of my career, a few colleagues had decided to act as my “guides and guardians” (Zeichner, 1983: 9). These colleagues boosted my morale and provided wise counsel.

That was 35 years ago and over the years I have often wondered how many other novice teachers have had negative experiences but without the guides and guardians who came to my rescue. How many of these novices travelling alone decided to abandon the teaching path before ever discovering the joys of teaching? As a result, I have always taken special interest in the development of novice teaching professionals in TESOL, their experiences and especially their well-being (the issues and challenges they face), as well as in how they are prepared (or not prepared) for their first years of teaching (e.g., Farrell, 2003, 2006a,b, 2007a,b, 2008a,b,c, 2009, 2012). Yes, there are many novice language teachers who seem to be able to navigate their first years successfully either largely on their own or thanks to supportive administrators, staff and fellow teachers. Unfortunately, it seems that supportive environments are the exception rather than the rule. Too often novice teachers are left to survive on their own in less than ideal conditions and, as a result, some drop out (as in teacher attrition) of the profession early in their careers (Crookes, 1997; Peacock, 2009).

So I would say the reality is that we are still not preparing our teacher learners adequately about how to deal with the realities of teaching in a real classroom (Faez & Vaelo, 2012; Wright, 2010). Unfortunately, some teacher educators, teachers, students and administrators still assume that once novice teachers have graduated from a teacher preparation programme they will be able to apply what they have learned during their first year of teaching. However, research in general education has indicated that the transition from the teacher education programme to the first year of teaching has been characterized as a type of “reality shock” because of “the collapse of the missionary ideals formed during teacher training by the harsh and rude reality of classroom life” and by the realities of the social and political contexts of the school (Veenman, 1984: 143). This reality shock is often aggravated because novice teachers have not one, but two complex jobs during these years: “teaching effectively and learning to teach” (Wildman, Niles, Milagro, & McLaughlin, 1989: 471). Thus, during the transition from training to teaching novice teachers, as Richards (1998: 164) points out, must be able to construct and reconstruct “new knowledge and theory through participating in specific social contexts and engaging in particular types of activities and processes.”

During this transition period, some novice language teachers may realize that they have not been adequately prepared for how to deal with these two different roles (Peacock, 2009), and may also have discovered that they have been set up in their pre-service courses (and teaching practice) for a teaching approach that does not work in real classrooms, or the school culture may prohibit implementation of these “new” approaches (Shin, 2012). Consequently, many novice teachers are left to cope on their own in a sink-or-swim type situation (Varah, Theune, & Parker, 1986). Continuing the theme of the relative weak impact of language teacher education programmes on the actions of novice teachers, Freeman (1994) cautioned language educators and novice teachers alike that most of what is presented in language teacher education programmes may be washed away by the first year experiences of becoming a novice teacher, a point also confirmed later in research studies by Richards and Pennington (1998) and by Farrell (2003).

In addition, language teacher education programmes may be at fault because they are not delivering relevant content that novice language teachers can implement in real classroom settings (Johnson, 2013). As Tarone and Allwright (2005: 12) argue, “differences between the academic course content in language teacher preparation programs and the real conditions that novice language teachers are faced with in the language classroom appear to set up a gap that cannot be bridged by beginning teacher learners.” Indeed, Johnson (2013: 75) has recently noted the “disjuncture between teachers’ own instructional histories as learners and the concepts they are exposed to in SLTE programs epitomizes the persistent theory/practice divide that remains a major challenge for SLTE programs today.” She goes on to say that it is the responsibility of SLTE programmes to present concepts they think are important to teachers, “but to do so in ways that bring these concepts to bear on concrete practical activity, connecting them to everyday concepts and the goal-directed activities of everyday teaching” (2013: 76).

Learning to teach in the first year is thus a complex process for novice teachers to go through (Bruckerhoff & Carlson, 1995; Featherstone, 1993; Solomon, Worthy & Carter, 1993) because they are faced with specific challenges that must be addressed if they are not to abandon the profession after only a short period of time (Varah, Theune, & Parker, 1986). It is important to ask how second language teacher education programs could bridge this gap more effectively and thus better prepare novice teachers for the challenges they may face in the first years teaching.

Laying the foundation(s)

How should be try to address the issues outlined above or in other words, how should we check this reality? First I would suggest that SLTE and second language teacher educators should not only focus on the formal period of the teacher education program but also include the novice years of teaching. I define novice teachers as those who are sometimes called newly qualified teachers (NQTs), and who have completed their language teacher education programme (including teaching practice) and commenced teaching TESOL in an educational institution (usually within three years of completing their teacher education program). I see three years as realistic (Huberman, 1989: 199, calls this the novice period: “career entry years”). As can be observed with this definition, age is not relevant. It is general enough to include teachers in any context who have acquired a second license (endorsement) in teaching English to speakers of other languages as long as they have taken a particular course that qualifies them to become a TESOL teacher. I also can see where one can be a “novice” at instructing a new technology.

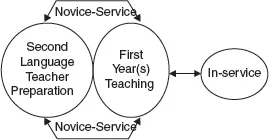

Unfortunately, what usually occurs is that on graduation from an SLTE programme most novice teachers suddenly have no further contact with their teacher educators, and from the very first day on the job must face the same challenges as their more experienced colleagues, often without much guidance from the new school/institution. These challenges include lesson planning, lesson delivery, classroom management and identity development. So in this chapter I also outline practical suggestions that can help bridge this gap, with the idea that novice teachers can experience the transition from teacher preparation to the first years of teaching as “less like ‘hazing’ and more like professional development” (Johnson, 1996: 48). I have called this bridging period, novice-service teacher education (Farrell, 2012). However, I now want to expand on the concept and suggest we eliminate the term pre-service and just have terms/concepts that address the issues of teacher education and development: novice-service to include second language teacher preparation (or the “old” pre-service term), and the first novice year(s) of teaching and then in-service to include any aspects of teacher education and development after the novice-service years. Figure 1.1 outlines a basic model of novice-service teacher education.

Figure 1.1 Novice-service teacher education

Novice-service teacher education

Novice-service teacher education begins in second language teacher preparation programmes and continues into the first years of teaching in real classrooms. It includes three main stakeholders – novice teachers, second language educators and school administrators – all working in collaboration to make for a smooth transition from the SLT preparation program to the first years of teaching. The idea is that the knowledge garnered from this tripartite collaboration can be used to better inform SLT preparation educators/programmes so that novice teachers can be better prepared for the complexity of real classrooms. For example, working in the US context Margo DelliCarpini and Oslando noted that ESL teachers were struggling with the demands of content where the content was that of the academic program in which their English language learner (ELLs) students were enrolled and where content teachers had a lack of awareness and understanding of the needs of ELLs in the mainstream classroom. They realized that this was an issue related directly to ESL teacher preparation so they devised what they call a two-way content based instruction (CBI) that builds on and extends teacher collaboration and traditional CBI. This innovation, they note, means that language-driven content objectives (which are enacted in the mainstream classroom) and content-driven language objectives (which are enacted in the ESL classroom) are collaboratively developed therefore eliminating the disconnect that is often present between language and content in the classroom.

SLT preparation

Johnson (2009: 11) proposed that the knowledge-base of second language teacher education programmes inform three broad areas: “(1) the content of L2 teacher education programs: What L2 teachers need to know; (2) the pedagogies that are taught in L2 teacher education programs: How L2 teachers should teach; and (3) the institutional forms of delivery through which both the content and pedagogies are learned: How L2 teachers learn to teach.” However, there is still no consensus in TESOL about what specific courses, and if they are connected to teaching practice (TP), should be included in SLT preparation programmes, and as Mattheoudakis (2007: 1273) has observed, “The truth is that we know very little about what actually happens” in many of these courses. Part of the reason for this is that most SLT preparation programmes vary so much in their nature, content, length and even in their philosophical and theoretical underpinnings, and so it is no wonder, as Faez (2011: 31) has recently indicated, that there is still “no agreement in the field as to exactly what effective language teachers need to know.”

However, we can still point out several dimensions of knowledge, skills and awareness that educators agree are important for teacher learners to acquire in second language teacher education programmes in order to become effective teachers (Richards & Farrell, 2011). Among these dimensions Richards and Farrell (2011) suggest that a teacher’s ability to acquire both the discourse of TESOL as well as the ability to use effective classroom language is a key dimension. They also note that teacher-learning thus involves not only discovering more about the skills and knowledge (academic and pedagogical) of language teaching, and how to apply these in teaching, but also what it means to be a language teacher in terms of developing the identity of a language teacher in a particular context. In addition, Richards and Farrell (2013) have noted that teacher learners need to be sensitive to the norms that operate in the contexts in which they work as well as reflect on their practice in order to further develop their theories and concepts throughout their first years. I will not however enter into the debate of what should (or should not) be included in SLT preparation. Instead, I outline and discuss what should be added to existing courses within the programme (regardless of the philosophical and theoretical underpinnings of that programme), and the addition of one supplementary course that is focused exclusively on exploring the first years of teaching through reflective practice.

During SLT preparation programmes pre-service teachers can be better prepared for what they will face in their first years in two ways: the first way is by making clear connections, in all the preparation courses, to teaching in the first year by including reflective activities and assignments that are related to the subject matter of those courses (Farrell, 1999). Thomas Farrell uses a reflective assignment to promote critical reflection in a graduate course (called ‘sociolinguistics as applied to language teaching’) where students were encouraged to reflect not only on the materials and content they are exposed to, but also how the content of the course has impacted, and will continue to impact, them both professionally and personally in their first years and beyond as language teachers. All thirteen participants in the course noted the value of such a reflective assignment as a means of developing an awareness of self as a future teacher that they may not have been able to develop alo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Series Editors’ Preface

- Notes on Contributors

- 1 Second Language Teacher Education: A Reality Check

- 2 Constructivist Language Teacher Education: An Example from Turkey

- 3 Encouraging Critical Reflection in a Teacher Education Course: A Canadian Case Study

- 4 Teaching Everything to No One and Nothing to Everyone: Addressing the Content in Content Based Instruction

- 5 Dissonance and Balance: The Four Strands Framework and Pre-Service Teacher Education

- 6 Materials Design in Language Teacher Education: An Example from Southeast Asia

- 7 Translanguaging Principles in L2 Reading Instruction: Implications for ESL Pre-Service Teacher Programme

- 8 Creative Enactments of Language Teacher Education Policy: A Singapore Case Study

- 9 Changing Practice and Enabling Development: The Impact of Technology on Teaching and Language Teacher Education in UAE Federal Institutions

- 10 Using Screen Capture Software to Improve the Value of Feedback on Academic Assignments in Teacher Education

- 11 Developing Novice EFL Teachers’ Pedagogical Knowledge through Lesson Study Activities

- 12 Reflective Practice as Innovation in SLTE

- Index