eBook - ePub

Finance and the Macroeconomics of Environmental Policies

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Finance and the Macroeconomics of Environmental Policies

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This volume examines current and previous environmental policies, and suggests alternative strategies for the future. Addressing resource depletion and climate change are pressing priorities for modern economies. Planning energy infrastructure projects is complicated by uncertainty, as such clear government policies have a crucial role to play.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Finance and the Macroeconomics of Environmental Policies by P. Arestis, M. Sawyer, P. Arestis,M. Sawyer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Macroeconomics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Absence of Environmental Issues in the New Consensus Macroeconomics is only One of Numerous Criticisms

Philip Arestis

University of Cambridge

Ana Rosa González-Martínez

Cambridge Econometrics

Abstract

This contribution focuses on the New Consensus Macroeconomics (NCM) theoretical framework. It outlines and gives a brief explanation of the main elements and way of thinking about the macroeconomy from the point of view of both its theoretical and policy dimensions. There are many problems with this particular theoretical framework. The most important in terms of the focus of this contribution is the absence of environmental issues. A number of further problems related to the New Consensus Macroeconomics, and its macroeconometric counterpart (Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium modelling), are summarised. We elaborate, though, on the problematic nature of the microfoundations of the macroeconomics dimension in the NCM theoretical framework in addition to the absence of environmental issues.

Keywords: New Consensus Macroeconomics; microfoundations of macroeconomics; environmental issues

JEL Classification: E10, E13, E52, Q50

1.1 Introduction1

The ‘New Consensus Macroeconomics’ (hereafter NCM) is now firmly established in both academia and economic policy circles, and draws heavily on the so-called new Keynesian economics (see Woodford, 2003, for a detailed elaboration, where the term neo-Wicksellian is utilised). NCM has managed to encapsulate those macroeconomic developments, including rational expectations. Galí and Gertler (2007) suggest that the New Keynesian paradigm, which arose in the 1980s, provided sound microfoundations along with the concurrent development of the real business cycle approach which promoted the explicit optimisation behaviour aspect. Those developments, along with macroeconomic features that were absent from previous paradigms, such as the long-run vertical Phillips curve, resulted in the development of the NCM. However, the ‘great recession’ has forced the profession to seriously begin to re-examine the theoretical and policy propositions of the NCM. Blanchard (2011), for example, argues that the crisis ‘forces us to do a wholesale reexamination of those principles’ (p. 1).

We focus in this contribution on the NCM in the case of an open economy (see also, Arestis, 2007a, 2007b, 2009b, 2011). We outline and briefly explain both the main theoretical and the policy dimensions of this macroeconomic framework. The policy implications in terms of its upgrading of monetary policy and downgrading of fiscal policy are highlighted. There are, however, some serious problems with this particular theoretical framework. We give a brief discussion of these problems along with the dimension of the microfoundations of macroeconomics, but highlight the absence of environmental issues in the NCM. In the process of our analysis we point out the important distinction between theoretical and policy issues.

We begin in section 1.2, after this introduction, by examining the open economy aspect of the NCM, which allows us to pay some attention to be given to the exchange rate channel of the transmission mechanism of monetary policy in addition to the aggregate demand channel and the inflation expectations channel. The NCM policy implications are examined in the same section. In section 1.3 we move on to a critical appraisal of NCM and its policy implications, in which we summarise a number of criticisms. Section 1.4 then deals with the aspect of the microfoundations of macroeconomics. Section 1.5 focuses on the main criticism of this contribution, namely the absence of environmental issues. Section 1.6 finally summarises the paper and offers some conclusions.

1.2 An open economy New Consensus Macroeconomics and policy implications

We begin by discussing the open economy NCM model, before moving on to consider its policy implications.

1.2.1 The open economy NCM model

Drawing on Arestis (2007b, 2011; see also Angeriz and Arestis, 2007), we utilise the following six-equation model for the open economy NCM model.

where a0 is a constant, Yg is the domestic output gap (the difference between actual output and trend output; the latter is the output that prevails when prices are perfectly flexible, and as such it is a long-run variable, determined by the supply side of the economy). Ygw is world output gap, R is nominal rate of interest, with Rw being the world nominal interest rate, p is the rate of domestic inflation, pw is the world inflation rate, and pT is the target inflation rate. RR* is the ‘equilibrium’ real rate of interest, that is the rate of interest consistent with zero output gap, which implies from equation (2) a constant rate of inflation; (rer) stands for the real exchange rate, and (er) for the nominal exchange rate, defined as in equation (1.6) and expressed as foreign currency units per domestic currency unit. Pw and P (both in logarithms) are world and domestic price levels respectively, CA is the current account of the balance of payments, si (with i = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) represents stochastic shocks, and Et refers to expectations held at time t. The change in the nominal exchange rate, as it appears in equation (1.2), can be derived from equation (1.6) as in Δer = Δrer + pwt − pt.

Equation (1.1) is the aggregate demand equation with the current output gap determined by the past and expected future output gap, the real rate of interest and the real exchange rate (through effects of demand for exports and imports). Equation (1.1) emanates from intertemporal optimisation of the expected lifetime utility of the representative agent who never defaults on debts, and under the assumption of short-run wage and price rigidities or frictions of the type outlined in Calvo (1983). This optimisation reflects optimal consumption smoothing subject to a budget constraint. It is, thus, a forward-looking ‘expectations’ relationship, which implies that the marginal rate of substitution between current and future consumption, ignoring risk and uncertainty and adjusted for the subjective rate of time discount, is equal to the real rate of interest. The intertemporal utility optimisation is based on the assumption that all debts will ultimately paid in full, thereby removing all credit risks and defaults. This follows from the assumption of what is known technically as the transversality condition, which means in effect that all economic agents with their rational expectations are perfectly creditworthy; no agent would ever default. All IOUs in the economy can, and would, be accepted in exchange. There is, thus, no need for a specific monetary asset. All fixed-interest financial assets are identical so that there is a single rate of interest in any period. Under such circumstances no individual economic agent or firm is liquidity constrained. There is, thus, no need for financial intermediaries (commercial banks or other non-bank financial intermediaries) and even money (see, also, Goodhart, 2004, 2007, 2009). Clearly, then, by basing the NCM model on the transversality condition, the supporters have turned the model into an essentially non-monetary model. It is thereby no surprise that private banking institutions or money variables are not essential in the NCM framework.2

Furthermore, there is the question of the role played by investment. The basic analysis (Woodford, 2003, chapter 4) is undertaken for households optimising their utility function in terms of the time path of consumption. Investment can then be introduced in terms of the expansion of the capital stock, which is required to underpin the growth of income. Investment ensures the adjustment of the capital stock to the predetermined time path. There is then, by assumption, the absence of what we may term an independent investment function in the sense of it arising from firms’ decisions taken in the light of profit and growth opportunities, separated from saving decisions of households. Woodford (op. cit.) summarises the argument rather well: ‘One of the more obvious omissions in the basic neo-Wicksellian model... is the absence of any effect of variations in private spending upon the economy’s productive capacity and hence upon supply costs in subsequent periods’ (Woodford, 2003, p. 352). The lack of an investment function also means that the distribution of investment between sectors and types cannot be analysed.

Equation (1.2) is a Phillips curve, which is derived from the intertemporally-optimising representative firm in a model of staggered price setting as, for example, in Calvo (1983). Inflation in equation (1.2) is based on the current output gap, past and future inflation, expected changes in the nominal exchange rate, and expected world prices (and the latter pointing towards imported inflation). The model allows for sticky prices in the short run, the lagged price level in this relationship, and full price flexibility in the long run. It is assumed that b2 + b3 + b4 = 1 in equation (1.2), thereby implying a vertical Phillips curve in the long run. The assumption of a vertical long-run Phillips curve implies no voluntary unemployment. This is clearly not acceptable, as some contributors have pointed out (see, for example, Blanchard, 2008). The way to introduce unemployment into the NCM model is still to be undertaken. The term Et(pt+1) in equation (1.2) captures the forward-looking property of inflation determination. It actually implies that the success of a central bank in containing inflation depends not only on its current policy stance but also on what economic agents perceive that stance will be in the future. The assumption of rational expectations is important in this respect. Agents are in a position to know how the economy works and also the future consequences of the actions that take place today. This implies that economic agents know how monetary authorities would react to macroeconomic developments, which influence their actions today. In this sense the practice of modern central banking can be described as the management of private expectations. Consequently, the term Et(pt+1) can be seen to reflect central bank credibility. If a central bank can credibly signal its intention to achieve and maintain low inflation, then there will be a lowering of the expectations of future inflation rates. This term, therefore, indicates that it may be possible to reduce current inflation at a significantly lower cost in terms of output than otherwise. In this way monetary policy operates through the expectations channel. This view of credibly anchoring inflation expectations has been criticised because of its failure to demonstrate whether price setters change their decisions on the basis of what their expectations of what inflation would be in the future (Blanchard, 2008, p. 21). Expected changes in import prices and in the nominal exchange rate are another two important determinants of inflation as shown in equation (1.2).

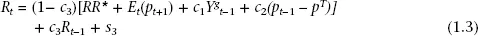

Equation (1.3) is a monetary-policy rule, which can be derived from the optimisation of the monetary authorities’ loss function subject to the constraints imposed by the economy’s structure as summarised in the structural model utilised. This process produces a model-specific optimal interest rate reaction function, which determines the optimal rate of interest as a function of state variables. In equation (1.3) the nominal interest rate thereby derived is related to expected inflation, output gap, the deviation of inflation from the target (the so-called ‘inflation gap’), and the ‘equilibrium’ real rate of interest. The lagged interest rate (often ignored in the literature) represents interest rate ‘smoothing’ undertaken by the monetary authorities. Equation (1.3) actually provides a fundamental correction of a theoretical weakness of how central banks operate (Goodhart, 2009). Namely, they adjust the rate of interest in a reaction-function manner, rather than exogenously; and that controlling the monetary base is not normally an objective of monetary policy. Equation (1.3), the operating rule, implies that ‘policy’ becomes a systematic adjustment to economic developments in a predictable manner. Inflation above the target leads to higher interest rates to contain inflation, whereas inflation below the target requires lower interest rates to stimulate the economy and increase inflation. Also, and in the tradition of Taylor rules (Taylor, 1993, 1999, 2001), the exchange rate is assumed to play no role in the setting of interest rates (except in so far as changes in the exchange rate have an effect on the rate of inflation, which clearly would feed into the interest rate rule). The monetary policy rule in equation (1.3) embodies the notion of an equilibrium rate of interest, labelled as RR*, defined as the ‘equilibrium real rate of return when prices are fully flexible’ (Woodford, 2003, p. 248). Equation (1.3) indicates that when inflation is on target and output gap is zero, the actual real rate set by monetary policy rule is equal to this equilibrium rate. This implies that provided the central bank has an accurate estimate of RR* then the economy can be guided to an equilibrium of the form of a zero output gap and constant targeted inflation rate. In this case, equation (1) indicates that aggregate demand is at a level that is consistent with a zero output gap. This would imply that the real interest rate RR* brings equality between (ex ante) savings and investment. This equilibrium rate of interest corresponds to the Wicksellian ‘natural rate’ of interest (Wicksell, 1898), which equates savings and investment at a supply-side equilibrium level of income.

Equation (1.4) determines the exchange rate as a function of the real interest rate differentials, current account position, and expectations of future exchange rates (through domestic factors such as risk premiums, domestic public debt, the degree of credibility of the inflation target, and so on). Equation (1.5) determines the current account position as a function of the real exchange rate, domestic and world output gaps. Equation (1.6) expresses the nominal exchange rate in terms of the real exchange rate. It should be emphasised that exchange rate considerations are postulated (as in equation (1.3)) not to play any direct role in the setting of interest rates by the central bank. This treatment of the exchange rate in the NCM framework has been criticised by, for example, Angeriz and Arestis (2007), in that ignoring it there is the danger of a combination of internal price stability and exchange rate ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Preface

- Notes on Contributors

- 1 The Absence of Environmental Issues in the New Consensus Macroeconomics is only One of Numerous Criticisms

- 2 The Neoliberal Trajectory, the Great Recession and Sustainable Development

- 3 The Macroeconomics and Financial System Requirements for a Sustainable Future

- 4 Financing Energy Infrastructure

- 5 The Effects of the Financial System and Financial Crises on Global Growth and the Environment

- 6 Dualisms in the Finance–Economy–Climate Nexus: An Exploratory Essay Drawing on Derridean Thinking

- 7 The ‘Dark Matter’ in the Search for Sustainable Growth: Energy, Innovation and the Financially Paradoxical Role of Climate Confidence

- 8 On Climate Change and Institutions

- Index