This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Drawing on the author's four decades of experience as a practitioner and academician working with private equity investors, entrepreneurs, and policymakers in over 100 developing countries around the world, this book uses anecdotes and case studies to illustrate and reinforce the key arguments for private equity investment in emerging economies.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Private Equity Investing in Emerging Markets by R. Leeds in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Financial Services. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

A Private Equity Primer*

Private equity offers a compelling business model with significant potential to enhance the efficiency of companies both in terms of their operations and financial structure. This has the potential to deliver substantial rewards both for the companies’ owners and for the economy as a whole.

—Financial Services Authority of the United Kingdom, Private Equity: A Discussion of Risk and Regulatory Engagement, November 2006

On the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro, far from the pristine beaches and luxury apartments of Copacabana and Ipanema, Claudio, the owner of a midsize company that provides scaffolding equipment for large construction projects, was reflecting on the turbulent history of his 40-year-old business.1 “We had a fantastic reputation! The company had a steady stream of reliable clients, a great brand name, and gradually we became a leader in our market. But no matter how fast we grew our revenues, the company was always encountering financial difficulties because we took on too much short-term debt. We never made any money.” This paradox of growth without profitability is a frustrating pattern repeated by “successful” entrepreneurs throughout the developing world. And for those who survive, the story usually gets even worse.

“By 2002–2003,” he continued, “the Brazilian economy was beginning a period of explosive economic growth, creating unprecedented opportunities for the construction industry. Although we had been the market leader in our specialized niche, I realized the company would quickly lose market share unless we could rapidly expand and respond to the huge increases in demand for our products. The construction materials sector in Brazil was highly fragmented, and I knew consolidation was inevitable as the building boom picked up momentum. Only those companies with access to the capital required to make new investments, achieve scale, and grow quickly would endure. I had learned from experience that the banks were useless. Even for a well-established company with a good track record in a booming market, they only offered short-term loans with crippling collateral requirements at sky-high interest rates. We even tried the government-owned development bank, and although they claimed to be interested in SMEs like us, I quickly realized they would be too slow and bureaucratic to solve our problem.

“In order to survive, we needed to attract an investor who recognized our company’s potential and would be willing to make a long-term commitment. Luckily, a friend of a friend introduced me to a private equity fund manager who specialized in making investments in small Brazilian companies with rapid growth potential. During our initial meetings, the prospective investor was extremely demanding, and I became skeptical that we’d ever strike a deal. But after an extended period of time and some very tough negotiations, we reached an agreement for the firm to invest a significant amount of capital for a 15 percent equity stake in the company.

“Our entire mind-set changed once these private equity investors were on our Board. From day one, they were active, hands-on, and sharply focused on specific improvements that would strengthen our performance. For example, although we already had reasonably good corporate governance standards, they offered wisdom we simply did not have, and we were able to strengthen our accounting and financial disclosure practices in line with international best practices. They also gave us more credibility with banks, and suddenly we were getting longer-maturity loans. And with their additional capital and expertise, we were able to execute a more aggressive acquisitions strategy, which accelerated our growth trajectory.”

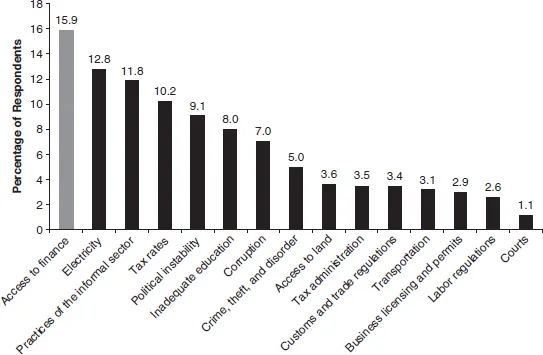

The financing problems experienced by this Brazilian entrepreneur are painfully familiar to owners of companies across the developing world. No matter how hardworking and successful, sooner or later they hit the same wall: limited or nonexistent access to medium- and long-term financing, which they require to grow and compete. As a result, these firms underperform relative to their potential. This linkage between access to capital and firm performance is indisputable, and is reinforced by countless surveys of business owners in a broad range of developing countries who consistently assert that the difficulty of obtaining financing ranks is one of their biggest problems (see Exhibit 1.1).2 According to one World Bank study, in low-income countries, 43 percent of small enterprises and 38 percent of medium-sized firms report access to finance as a major obstacle to their business operations; in high-income countries, only 17 percent and 14 percent, respectively, of firms report this as a constraint.3 In addition, numerous companies similar to Claudio’s do not reach their full potential because their owners or management teams lack the necessary business know-how—whether operational, financial, marketing, corporate governance, or otherwise. Just as capital is scarce and difficult to come by, so is value-creating operating expertise.

Exhibit 1.1 Growth Constraints Reported by SMEs

Source: Adapted from The World Bank (2014), Enterprise Surveys, www.enterprisesurveys.org, The World Bank.

A special breed of investors is attracted to companies throughout the developing world that are underperforming for reasons similar to Claudio’s firm. Private equity investors are in the business of providing a combination of scarce capital and performance-enhancing expertise for the purpose of strengthening the competitiveness and profitability of individual companies that meet their rigorous investment criteria. When these efforts are successful, company value is significantly enhanced, eventually generating attractive financial returns both for the investors and the owners of the target companies. Moreover, this private equity investment approach has the potential to create a virtuous circle: reams of research validate the proposition that, regardless of the country circumstances, a more productive, competitive private sector generates higher rates of economic growth and lower levels of poverty.

To grasp the full potential impact of private equity in developing countries, however, first requires a clear understanding of what private equity is, and how this particular financing tool is uniquely endowed with characteristics that make it different from all other such mechanisms available to private companies. In addition as will be argued in subsequent chapters, it is particularly well suited for a diversified range of businesses in developing countries worldwide.

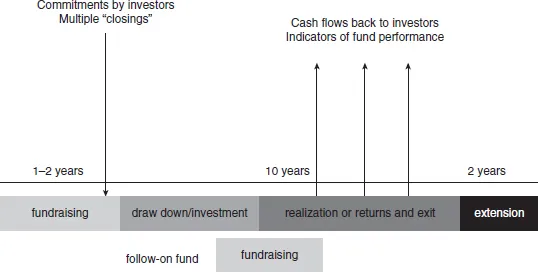

Understanding the unique fundamentals of private equity

Traditionally, the term “private equity” has been used to describe an equity investment in a firm that is “private,” meaning not listed on a public stock exchange. In developed countries, private equity also refers to the buyout of a public company, which then results in its delisting from an exchange.4 Aside from buyouts, these transactions are commonly large enough for an investor to gain a significant, but not necessarily a controlling, equity ownership stake in the company. The investor’s goal is to carefully select firms with exceptionally high growth potential, work closely with management once the capital has been invested to build value and strengthen performance (typically over a period of three to five years), and then “exit” by selling the shares at a significantly higher price than was originally paid, generally either through an initial public offering (IPO) or via a sale to a strategic investor or corporation (see Exhibit 1.2). Less frequently, fund managers may sell their stake to another private equity fund, or back to the management, known as a management buyout (MBO).

Exhibit 1.2 The Private Equity Timeline5

From the early stages of marketing a fund to prospective investors and the initial screening of deals, to the final exit of the last portfolio company, the life of a private equity fund typically lasts about eight to ten years. However, private equity fund managers often begin fundraising for a follow-on fund before the final exits have occurred in the previous one.6 This ensures an ongoing continuity of operations.

The private equity organizational structure (see Exhibit 1.3) and means of compensation are distinct from that of other financial intermediaries. Whether well-established multibillion-dollar global asset managers such as The Carlyle Group, Blackstone, KKR, or Warburg Pincus, or small venture capital funds targeting entrepreneurial start-ups, typically, these entities are legally structured as limited liability partnerships (LLPs).7 The private equity fund manager, also known as the general partner (GP), raises a pool of capital primarily from institutional investors and other accredited investors, called limited partners (LP).8 Once LPs commit their capital, all responsibility is delegated to the GP, from deal origination to the exiting process. In other words, the LP is a passive investor in the designated fund, with no decision-making authority on individual investments.

Exhibit 1.3 Basic Organization of the Private Equity LLP Fund Structure

Although a range of investors potentially falls into the LP category, the most prominent are large financial intermediaries such as public and corporate pension funds, banks and insurance companies, university endowments, some family offices, and state-owned sovereign wealth funds.9 These fiduciary institutions are entrusted with the responsibility to manage and invest large pools of capital in a diversified portfolio of financial assets representing different risk profiles, from low-risk government bonds on one end of the spectrum to so-called alternative investments, such as private equity, on the other. Significantly, these institutions tend to have an investment philosophy that allows them to be less concerned with short-term market volatility than many other investors (such as hedge funds) and, as a result, they are more tolerant of the illiquidity associated with private equity.

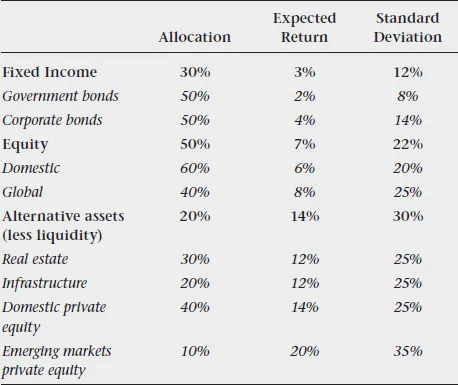

Placing Private Equity within an Asset Allocation Bucket—an Illustrative Portfolio

The term “asset class” conveniently distinguishes between different financial assets based on assumptions about their risk, return, and liquidity characteristics. Although there is no universally accepted classification system, institutional investors managing large pools of capital tend to make allocations across a diversified spectrum of financial assets with similar characteristics according to their risk/return preferences. For example, a US university endowment might make investments on the basis of the following allocation:

According to convention, therefore, private equity is categorized as a distinct asset class because it is perceived by investors to offer higher returns, but also higher risks and volatility (based on standard deviation calculations). But this book contends that an additional distinction should be made by investors: emerging markets private equity should be viewed as a distinct asset class, endowed with a set of risk/return characteristics different from that of private equity in developed countries.

These institutions are attracted to the LLP structure because of their preference to rely on specialized intermediaries or GPs, especially in the complex and opaque world of private equity. As one pension fund manager acknowledged, direct investing in individual companies [for us] is time consuming and “inherently awkward.” Investing in a private equity fund, therefore, is far more efficient in terms of time allocation, not to mention the higher probability of generating attractive financial results by relying on the expertise of specialized professionals. As an alternative to investing directly in GPs, LPs also have the option of committing their capital to a “fund of funds,” which makes investments in a number of different GPs. Some LPs prefer this approach as it offers the opportunity to diversify their investment risk across a broader spectrum of GPs in terms of geography, strategy, track record, and sector-specific skills. On the flip side, a handful of LPs are bolstering their teams in order to do direct private equity investing, thus bypassing the GP and investing directly in private businesses. However, by and large, these institutional investors have been committing capital to the asset class for decades and believe they have built up the required skill sets to implement such a strategy.

The ILPA Private Equity Principles—a Guide for the LP-GP Relationship

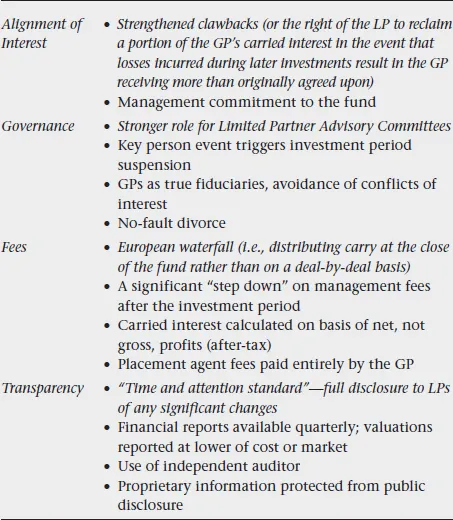

The Institutional Limited Partners Association (ILPA)—a trade association representing the interests of institutional limited partners invested in or considering investing in private equity—established the Private Equity Principles in September 2009 (updated in 2011) to assist LPs and GPs in clarifying the terms of their relationship. The Principles reflect the LP point of view on the terms and conditions that should constitute best practices, with particular attention to promoting enhanced GP governance and transparency, as well as fee structures that better reflect LP financial interests. While not intended to be a “one size fits all” approach, the Principles provide LPs a set of specific guidelines for their negotiations with GPs.

A sampling of key topics addressed in the Principles includes:

Compensation structures represent one of the most distinctive features of private equity compared to other financial intermediaries. The GP receives two primary forms of remuneration: an annual “management fee,” calculated as a fixed percentage of the total amount of capital in the fund (usually between 1 percent and 2.5 percent, depending on the total fund size), and “carried interest,” which is performance compensation based on the net capital gain generated at the time of exit in excess of a minimal “hurdle rate of return” paid to the LPs (typically 6 to 8 percent). The standard practice in the industry is to pay 80 percent of the carried interest to the LPs and 20 percent to the GP, often referred to as an 80/20 split. Thus, the largest portion of compensation for private equity investors is received only at the end of the process, usually many years after the original cap...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 A Private Equity Primer

- 2 Private Equity Ecosystems: A Stark Contrast between Developed and Developing Countries

- 3 The Private Equity Advantage: Operational Value Creation

- 4 Private Equity Performance before the Global Financial Crisis

- 5 A Post-crisis Assessment: New Challenges and Opportunities

- 6 China: Private Equity with Chinese Characteristics

- 7 Brazil: The Country of the Future

- 8 Kenya: Challenges and Opportunities in a Frontier Market

- 9 Looking through a Hazy Crystal Ball

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index