This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Investigative Journalism, Environmental Problems and Modernisation in China

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book examines how the news media in general, and investigative journalism in particular, interprets environmental problems and how those interpretations contribute to the shaping of a discourse of risk that can compete against the omnipresent and hegemonic discourse of modernisation in Chinese society.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Investigative Journalism, Environmental Problems and Modernisation in China by J. Tong in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sciences biologiques & Science environnementale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Sciences biologiquesSubtopic

Science environnementale1

Modernisation, Environmental Problems and Chinese Society

This chapter maps the relationship between the emergence of environmental problems and China’s modernisation. It also discusses the responses of various parties – the state, transnational and national businesses, society – to these issues. It suggests that the importance of the emergence of environmental issues should be understood in the light of their relationship to society, taking into account the potency of social dynamics, especially the interaction between global capitalism and domestic power relations, the development of civil participation, social class differentiation, as well as consumer culture and lifestyles, and of the social logic regarding the relationship between development and the environment.

In its ongoing process of modernisation since 1949, China has transformed itself from an agricultural into an industrial society. Parallelling this domestic process, Western capital has continually sought expansion in the global arena. Developments in transportation and information technologies have provided the material infrastructure for such an expansion. With its enormous natural resources and cheap labour, China offers an ideal opportunity for the expansion and ambitions of global capital. The corollary of increased globalisation has been China becoming pivotal to global production chains, assuming the role of the world’s factory.

Capitalism’s pursuit of capital accumulation and maximal profits by its very nature places it in opposition to the preservation of the environment. Its impacts on the environment are also exacerbated by the Chinese leadership’s ignorance of sustainable development and its belief in Man’s capability and right to conquer nature. As a result, the environment is threatened by a proliferation of economic activities encouraged in the modernisation process. Concurrently, Chinese society has experienced a series of dramatic social and political changes, such as the Cultural Revolution and the reforms aimed at opening up the country and accelerating growth, which have given rise to social tensions. As part of that process, environmental problems per se are related to power struggles among a variety of parties with particular interests, especially the state, enterprises and society generally. The news media are a principal site in which these power struggles are negotiated. Chinese media have hitherto played an uncertain role, although many media outlets have given enduring and extensive attention to environmental issues. The genesis of this uncertainty can be ascribed to the unique relationship between the news media and various social actors emerging in the authoritarian context of contemporary China.

The chapter starts with an overview of the features of modernisation and then turns to a discussion of the advent of environmental problems as a consequence of modernisation. After that it looks into the way the state, enterprises and society have responded to the worsening environmental situation. A discussion of their responses reveals the mutual influence between social dynamics and environmental problems and how that influence leads to the ways in which environmental problems are seen at the present time. An overview of the attention paid by the news media to environmental problems and issues follows. The chapter concludes by raising two questions: How do the Chinese news media – and in particular investigative journalists – mediate the respective interests of different parties and opposing viewpoints on environmental issues, and what does such a mediating role mean to China’s modernisation?

1.1 Modernisation: a utopian dream of “better lives”

As elsewhere in the world, China’s environmental problems are highly associated with its modernisation (here I mainly refer to economic modernisation) and industrialisation which are driven by a longing for a better quality of life. Such a desire for a better life was initiated by the leadership from the outset of the establishment of the People’s Republic, and quickly embraced by ordinary people. The goal of modernisation, a sweet dream the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has woven, has come to be accepted wholeheartedly by the people. Replacing the obvious ideologies promulgated during times of war, (economic) modernisation has become a hegemonic force that has cemented an unwritten agreement with the public and reinforced the leadership of the CCP. The hidden meaning behind modernisation is that to unite around the CCP is the best and only way to live a good life. Modernisation encompasses a utopian ideal that narrows social inequalities and eliminates poverty. At that time China had just emerged from international and civil wars. It urgently needed to put the economy back on its feet. People who had suffered war and poverty over a long period were easily convinced that the national priority should be given to economic growth in order to make the country stronger and improve people’s lives. Thus it was not a surprise to see the modernisation wave sweeping across the country from the 1950s. Industrialisation, the renaissance of agriculture and relevant scientific and technological innovations were officially promoted with the aim of bringing the economy forward and achieving national development.

Chinese modernisation can be divided into three phases. The first phase lasted from 1949 to the outbreak of the Cultural Revolution in 1966. As a close political ally of the Soviet Union, China took the same socialist road of modernisation, characterised by a planned economy and heavy-industry–oriented industrialisation. This phase witnessed a shift in the relationship between China and the Soviet Union in which China first relied on the Soviet Union to provide aid and later depended on itself for progress. China started to follow a separate path from the Soviet Union and even wanted to surpass it to become the leader of the socialist countries from the late 1950s. The Great Leap Forward was launched in 1958 for such a purpose but proved to be a failure in terms of both industrial and agricultural development (Rozman 1981). For example, one major purpose of this program was to promote collective mechanised agriculture and increase grain production within a short period of time in order to meet the needs of rapid industrialisation. A tragic result of this program, however, was a nationwide famine due to a sharp decline in crop production. An interesting study by Li and Yang drawing on empirical data collected from 1952 to 1977 has revealed that problems with central planning during the period from 1958 to 1961 were responsible for 61% of the decline in grain output (Li and Yang 2005). The launching of the Cultural Revolution campaign signalled the beginning of the second phase of China’s modernisation in which the economy was devastated and modernisation was almost halted because of the political trauma.

Modernisation restarted in the 1980s, entering its third phase, and witnessed a shift from a planned to a market economy. The 1980s was a crucial time in which the need by international capital for global expansion coincided with the concurrent requirement for domestic economic growth. The Fordist mode of production encountered a deep crisis of capitalism in Western domestic markets. Western capitalism urgently needed to transform its production mode and required global markets and resources (Castells 1996; Harvey 1990). Domestically, Deng Xiaoping and his allies launched extensive economic reforms to open up and boost the economy, though leaving political reform behind. The Eastern and Southern regions were the first to join the economic reform program, followed by the Western and Midland regions. While industrialisation and rapid and steady economic growth were the main objectives of the reforms, attracting foreign investment became one of the main means to increase the vitality of industries and boost GDP. Entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 further integrated China into the global economy.

The discussion above reveals one prominent feature of modernisation: for most of the time modernisation has meant economic development and industrialisation for China (Ho 2006). Despite the centrality of economic growth, modernisation is closely linked to or even defined by the dominant ideology in China (Wang and Karl 1998; Schwartz 1965). An authoritarian attitude by the ruling party towards modernisation and its determination to transform the lives of the people underpins modernisation, which not only means that giving its people a better life becomes an objective of the Party, but also suggests that this task has to be fulfilled by the Party itself (Schwartz 1965). More than half a century after Schwartz made that comment, the principle of the CCP’s authoritarian rule remains unchanged at the present time and the Party continues to assert that it supports socialism and has the aim of establishing social equality among people. Nevertheless, modernisation, that is, the central planning of social life by the Chinese government, is influenced and even limited by market principles and the logic of capitalism. Because of that, the relationship between the state (especially governments at all levels) and capital has become very intimate (Wang and Karl 1998). When modernisation penetrates into the everyday life of the people, the intimate connection between modernisation and the governing ideology means that modernisation underpins the foundations for the rule of the Party. The decades-long priority for modernisation has made it a hegemonic paradigm that legitimates the authoritarian regime. Core values of the state and later the principles of the market are conveyed to the people in order to be accepted by them. Therefore underlying the need for modernisation is the state’s hegemonic interest.

Underlying this is an ambivalent social attitude towards nature, promoted by the top leadership. On the one hand, resources are thought of as finite. Elite individuals and institutions, such as governments, should therefore take responsibility for managing finite resources. This attitude is best embodied in the national policy for controlling the growth in population which embodies fears over resource scarcity. Mao once expressed trust in the power of human resources with his famous saying “stronger with more people” (renduo liliang da). However, the population explosion from the 1950s to the 1990s caused the leadership to fear overpopulation and worry about resources and economic growth and resulted in the 1979 launch of the notorious “one child policy” that has been in force in recent decades. The Chinese population increased by 57% from 1949 to 1971 (Jing 2013). Such a fear is, in Dryzek’s terms, a kind of survivalist discourse of environmentalism (Dryzek 2005). Nonetheless, this survivalist discourse serves the development discourse of modernisation as, after all, the population is being controlled for the sake of development (Shapiro 2001).

On the other hand, there is an absolute confidence in humans’ capacity to conquer nature and handle environmental problems as well as in technology that is seen as supreme. The central leadership followed Marx’s and later Mao Zedong’s view of nature: seeing nature as an object to be conquered and used for production and progress purposes. Marx’s writings are thought to have embodied a Promethean attitude towards nature (Giddens 1981), although, also having paid attention to ecological issues such as the metabolic rift (Foster 1999a; Hannigan 2006: 8–9), Marx’s critique of the political economy of capitalism suggests the nature of capitalism is unsustainable and incompatible with nature (Foster 2010). Although Marx criticises capital’s exploitation of nature, his Promethean discourse expresses confidence in humans’ capability to overcome environmental problems and can be used to justify the national priority of economic growth (Dryzek 2005). The Maoist ideology for conquering nature further justifies and catalyses the exploitation of natural resources in the name of developing the national economy. This is well demonstrated in his famous sayings such as “men can conquer nature like the foolish man can move mountains” (yugong yishan rending shentian) and “it is endless fun fighting nature” (yutiandouqilewuqiong). During the pre-1980s years, this Promethean belief underpinned the planned economy as well as economic campaigns such as the Great Leap Forward and the Four Pests Movement in 1960s that were initiated by Mao and other political leaders (Shapiro 2001). This belief has remained intact over the past decades.

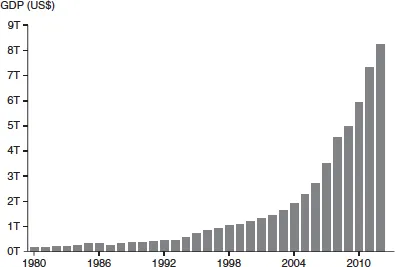

Indeed, spurred by the overall national priority for economic growth, China’s annual GDP has seen a steady increase (see Figure 1.1). From 2010, China has boasted of possessing the world’s second-biggest economy.1 While China is increasing its weight in the global economy, its economic achievements are mainly based on industrialisation. For example, more than half of the economic growth in 2011 came from “machinery, buildings and infrastructure”.2 Since the late 1980s, a massive amount of foreign investment has poured into China. Foreign-owned factories have been launched, enjoying beneficial policies and cheap resources and labour. Giant transnational corporations, such as Sony and Unilever, have moved their production centres to China. As a result of this China has become one of the world’s largest manufacturing centres. While the West has been transformed from an industrial to an information and knowledge economy in the post-Fordism era, China continues to produce hardware such as smartphones and computer accessories for the information and knowledge economy in the West.

After the 1980s, the Promethean belief and the Maoist attitude towards nature continued to function as the dominant principles that guided governments at all levels to develop local economies. The correlation between economic growth and political achievement further stimulated the enthusiasm of local governments in pursuing the growth of GDP. Local governments thus became obsessed with developing local economies and attracting foreign investment with little concern for environmental protection.

Figure 1.1 China’s GDP from 1980–2012, according to the World Bank DataBank3

Of course, against such a backdrop the lives of ordinary Chinese people have been highly improved. They are living a richer life nowadays than in the 1970s, especially those who live in cities. People’s lifestyles have changed alongside an increase in their income and the fact that consumption is no longer suppressed as it was under Maoist rule (Ngai 2008; Tse, Belk et al. 1989). People are no longer proud of being proletarian and living a poverty-stricken life. Rather they are longing for a bourgeois lifestyle that encourages a desire for commodities and a pursuit of consumption. Consumption of middle-class products, such as cars and houses, and activities such as tourism, can now be afforded by ordinary people. That affordability symbolises a widespread consumerism in Chinese society (Ngai 2008) which, however, is not environmentally friendly.

1.2 The emergence of environmental problems and issues

All the developments discussed above have been accompanied by the deterioration of the environment (Zhang, Mol et al. 2007; Guo and Kassiola 2010; MacBean 2007) which puts “a better life” in question. While China becomes a factory for the world and more inclined to consumerism, its need for resources increases and the exploitation of nature is deepened. As an inevitable result, its environment is suffering from local resource scarcity and environmental pollution. The seven major environmental problems identified by Ma and Ortolano (Ma and Ortolano 2000: 2) in the early 21st century can be classified into these two types. While the scarcity of resource results from an unsustainable use of resources, intensive production without effective environmental protection leads to the pollution of the environment. Some environmental problems can be seen by the naked eye. Obvious river and air pollution and desertification, for example, can be sensed by humans. However, many other environmental problems, such as resource scarcity, underwater pollution and species extinction, are only brought to the attention of the public by being reported.

Global capital poured into China for a number of reasons. Cheap labour and extensive natural resources are attractive to global capital, eager as it is to accumulate profits. It was predicted that as a result of becoming a new resource provider for global capital, China would witness a new age of resource scarcity by the end of the 1990s (Walker 1996). In the mid-1990s China ran short of energy and grain, which had to be imported from abroad. Walker argued such a shortage resulted in an increase in food and energy prices as well as a shifting price mechanism, meanwhile posing a threat to China’s dream of prosperity. Walker was far from being over-pessimistic. To take the energy shortage, for example, the situation in the new millennium is much worse than it was when his article was written. It has become widely accepted that the shortage of energy has become a crucial constraint on China’s economic growth and even stability. The Economist revealed China was facing a severe problem in this respect in 2007 and it took over from the United States as the world’s biggest energy consumer in 2011.4 In the same year it was reported that China was suffering the worst energy shortage in years.5

In recent years it has been widely reported that cities that once enjoyed resource-based economic growth have now turned into “ghost cities” due to exhausting those resources. The state made a list of 44 such cities in 2008 and 2009. The economies of these cities were developed quickly in the 1990s, thanks to the exploitation of enormous natural resources such as coal, copper, oil and forests that were formed over millions of years as a gift of nature. Natural resources nevertheless declined quickly within a mere dozen years as a result of overuse (Wang and Guo 2011). Most of these cities are in the western regions, such as Datong in Shanxi, Baiying in Gansu, Panzhihua in Sichuan, E’er dou si in Inner Mongolia. They once had massive underground natural resources, such as coal and copper. Encouraged by the “Western Great Development” (xibu dakaifa) policies, these cities attracted a wide range of capital because of their massive local resources. This capital met with local officials eager to become rich. The economies in cities such as Datong and E’er dou si indeed grew very fast. However, after only a few years their natural resource...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 Modernisation, Environmental Problems and Chinese Society

- 2 Twenty Years of Environmental Investigative Reporting: Agendas, Social Interests and Voices

- 3 The Discourse of Risk: Environmental Problems and Environmentalism in Chinese Press Investigative Reports

- 4 Environmental Investigative Journalists and Their Work

- 5 Offline Investigative Journalism and Online Environmental Crusades

- 6 Hegemony and Counter-Hegemony: Investigative Journalism between Modernisation and Environmental Problems

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index