eBook - ePub

Economic Management in a Volatile Environment

Monetary and Financial Issues

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Economic Management in a Volatile Environment

Monetary and Financial Issues

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book discusses some of the challenges relating to macroeconomic and financial management in a volatile and uncertain world brought about by greater financial openness. It explores the implications of a key set of issues emanating from financial globalisation on emerging market economies in a rigorous but readable manner.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Economic Management in a Volatile Environment by Ramkishen S. Rajan,Sasidaran Gopalan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Macroeconomics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I

Exchange Rates, Reserves, and Controls

1

What Is the Extent of Monetary Sterilisation in China?

(With A. Ouyang and T.D. Willett)

1 Introduction

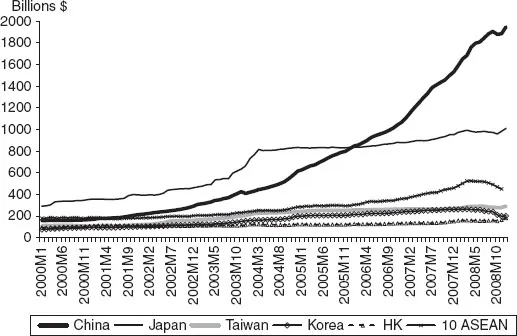

China is the world’s largest international holder, having amassed about US$ 2 trillion of international reserves by the end of 2008 (Figure 1.1), rising to US$ 3 trillion by 2010.1 The rapid accumulation of reserves by China has generated several controversies. One concern is whether this continuing balance of payments (BOP) surplus signals the need for a substantial revaluation or appreciation of the Chinese Yuan (CNY) to protect China both from the inflationary consequences of the liquidity buildup and a misallocation of resources2 as well as to help ease global imbalances. An alternative view, particularly associated with McKinnon and Schnabl (2003a,b; 2004), argues that a fixed exchange rate is an optimal policy for China and the larger Asian region both on the grounds of macroeconomic stability and rapid economic development. The global monetarist approach of McKinnon is based on the assumption of little or no sterilisation of reserve accumulation, so that any BOP imbalance is temporary. However, many other commentators have suggested that the Chinese government’s concern with inflation has led the People’s Bank of China (PBC) to heavily sterilise these reserve inflows.3

Contrary to the widespread concerns among many economists about the huge size of current global economic imbalances, Dooley et al. (2004) famously argued that mainstream economists have failed to recognise that we are now in a new informal version of the Bretton Woods system (BW2), and the global economy is therefore not in genuine disequilibrium. While there are clearly important analogies between the current international monetary system and Bretton Woods (BW1), the question is still open as to whether we are currently closer to the early or late days of BW1.4 In the later days of BW1, much attention was given to the concept of countries as reserve sinks into which reserves flowed. Instead of stimulating adjustments, as assumed in global monetarist models, the reserves effectively disappeared from the system (down the sink) and hence contributed to continuing disequilibrium. Germany was seen as the prototype of the reserves sink during the BW1 days. Today, China appears to be playing that role. Thus, investigating how China has reacted to its reserve increases is of international as well as national importance.5

Figure 1.1 Reserve growth in China and Japan and East Asia (billions of US$), Jan 2000–Dec 2008

Source: All the data are from International Financial Statistics (IFS), expect Taiwan. The data for Taiwan is from AREMOS Economic Statistical Databanks, which is published by Taiwan Economic Data Center (TEDC).

An intermediate view is that while China has sterilised most of its past reserve increases, continuing to do so is becoming increasingly difficult for China as its reserves continue to rise and capital controls become more porous (Prasad, 2005; Prasad and Wei, 2005; and Xie, 2006). One of the reasons why there is so much disagreement is because, as noted by Goodfriend and Prasad (2006), “(t)he fraction of reserves sterilised by the central bank has varied over the last few years and it is not straightforward to assess exactly how much sterilisation has taken place.”

This chapter estimates the degree of sterilisation in China, as well as the degree of capital mobility as measured by offset coefficients, that is, the fraction of an autonomous change in the domestic monetary base that is offset by international capital flows. In one sense, the level of sterilisation can be observed from the degree to which the central bank takes action to offset the effects of increases in international reserves on the domestic base or other monetary aggregates. However, this can offer a misleading picture of the effectiveness of sterilisation. If the central bank wants the base to increase anyway, then it would decide not to neutralise the reserve increases; this would not imply that it had lost control of the domestic monetary process. China’s large BOP surplus in 2003 was accompanied by rapid domestic money and credit expansion which is consistent with an inability to effectively sterilise. It appears, however, that the primary cause of the rapid expansion of money and credit was the Chinese government’s concern with maintaining rapid economic growth, not the inability of the PBC to control the domestic monetary base.6 Thus, the PBC did not try to fully neutralise the domestic monetary effects of the reserve increases under government direction.

To investigate the central bank’s ability to control domestic monetary aggregates, it is necessary to estimate the extent to which international flows undercut its control. This in turn requires the estimation of the counterfactual of the desired rate of monetary growth, that is, estimation of the central bank’s monetary reaction function. There is no one correct theoretical specification for central bank reaction function, but the literature has developed a standard set of variables to be considered within this function. This allows us – at least in principle – to break down the inter-relationship between international reserve changes and the monetary base into those relating to autonomous changes in the monetary base (the offset coefficient) and those relating to autonomous changes in international reserve flows (the sterilisation coefficient). We also make use of recursive estimation to investigate changes in offset coefficients and sterilisation over time. While we find no evidence of the inability of the government to sterilise a high proportion of reserve accumulation, we do find substantial increases over time in our estimates of the offset coefficients, suggesting that sterilisation is becoming increasingly difficult.

The next section briefly explores the evolution of the BOP flows in China since 1999– 2000, focussing on the magnitude and sources of reserve buildup as well as the monetary consequences of the buildup of reserves. It also briefly discusses the sterilisation policy measures used in China (de jure sterilisation). Section 3 offers a summary of the main empirical methodologies commonly used to estimate the de facto extent of sterilisation. As will be discussed, the estimation procedure used in this chapter is based on a set of simultaneous equations to estimate both the sterilisation coefficient (i.e., how much domestic money creation responds to a change in international reserves) and the offset coefficient (i.e., how much BOP changes in response to a change in domestic money creation). Since the foreign exchange and the domestic monetary markets are inter-related, ignoring such interrelationships can lead to biased results. Section 4 discusses the data and definitions of variables to be used in the empirics and presents the empirical results of the sterilisation and offset coefficients based on monthly data for the period from June 2000 to September 2008 (until the Global Financial Crisis (GFC)). This section also undertakes a number of robustness checks. The results remain remarkably stable to alternative estimation techniques used as well as to different proxies for exchange rate expectations and for valuation changes in international reserves. We also present a recursive estimation which suggests that the degree of sterilisation has fallen despite remaining substantial. The final section concludes with a brief discussion of the macroeconomic policy implications and tradeoffs facing China in the future.

2 Reserve growth and sterilisation policy measures in China since 1990

2.1 Evolution of China’s BOP7

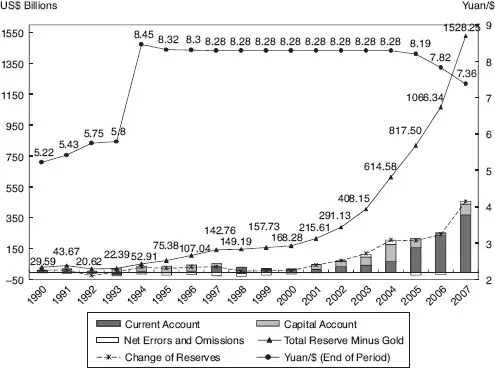

China has experienced large and growing surpluses on both the capital and current accounts since 2001. Even the errors and omissions balance (a broad proxy for capital flight by residents) turned positive (Figure 1.2). Thus, reserves increased markedly during this period. An interesting dynamic appears to have taken hold in China (as well as in many other Asian economies) during this period. Large reserves are viewed as a sign that the domestic currency will eventually appreciate. They also tend to be taken as an indication of “strong fundamentals”, hence leading to an upgrading of the country’s credit ratings. This expectation of future capital gains and lower risk perceptions motivated large-scale capital inflows and added to the country’s stock of reserves as central banks have mopped up excess US dollars.

From Figure 1.3, it is apparent that the swelling of China’s capital account surplus since 2003 was largely because of a surge in portfolio flows as well as “other investments” (i.e., short-term debt flows), most likely a reflection of mounting market expectations of an impending revaluation of the Chinese currency (i.e., speculation on the CNY as a one-way trade). As noted by Prasad and Wei (2005), “much of the recent increase in the pace of reserve accumulation is potentially related to ‘hot money’ rather than a rising trade surplus or capital flows such as FDI that are viewed as being driven by fundamentals” (p. 8).8 Goldstein and Lardy (2006) conclude, however, that even with hot money flows excluded, China faced a substantial BOP disequilibrium. IMF reports, in 2004, expressed doubts about whether the CNY was fundamentally undervalued and by 2006, the growing trade surplus had convinced most observers that the CNY was fundamentally undervalued. Estimates of the extent of undervaluation varied enormously, however.9

Figure 1.2 Trends in China’s BOP transactions (US$ billions), 1990–2007

Source: IFS, the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE)’s website and Taiwan Economic Journal (TEJ) Great China Database.

The Chinese government finally loosened its stric...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- I Exchange Rates, Reserves, and Controls

- II Financial Crises, Financial Liberalisation, and Foreign Bank Entry

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index