What Is Peacebuilding?

Peacebuilding as a concept is attributed to Boutros-Ghali in his 1992

Agenda for Peace paper (although Galtung first used the term in

1975). In this definition, Boutros-Ghali delineates between the United Nations Security Council’s different roles as follows:

- (a)

To seek to identify at the earliest possible stage situations that could produce conflict, and to try, through diplomacy, to remove the sources of danger before violence resulted;

- (b)

Where conflict had erupted, to engage in peace-making aimed at resolving the issues that had led to conflict; through peacekeeping, to work to preserve peace where fighting had been halted, and to assist in implementing agreements achieved by the peacemakers; and,

- (c)

To stand ready to assist in peacebuilding in its differing contexts; and to address the deepest causes of conflict: economic despair, social injustice and political oppression.

- (d)

(Boutros-Ghali 1992: 823; authors’ emphasis)

Post-conflict peacebuilding, he argued, ‘was action to identify and support structures which would tend to strengthen and solidify peace in order to avoid a relapse into conflict’ (Boutros-Ghali 1992: 823). Beyond this period a liberal peacebuilding hypothesis emerged which argued that the establishment of liberal institutions such as democracy, human rights, free markets and the rule of law were prerequisites for sustainable peace in countries which had suffered conflict. In other words, peacebuilding became synonymous with state-building or ‘the creation of democratic liberal economies is seen as a guarantor for peace’ (Paffenholz 2013: 348). As Ryan (2013: 32) points out: ‘none of these ideals seem inappropriate or contemptible in themselves and yet the liberal approach to peacebuilding has become the target of a number of critical studies’, but Ryan also cites grounds for scepticism: the approach is insensitive on the grounds of gender and class divisions and is blind to ethnic and national identity (Mac Ginty 2011; Richmond 2011).

Francis (2012) argues that there are two contrasting but linked definitions of peacebuilding—a narrow and a broad definition. In the former, peacebuilding involves interventions aimed at capacity-building, state reconstruction, reconciliation and societal transformation. In the latter, peacebuilding comprises security, political, economic, social and developmental interventions which attempt to strengthen political settlements and address the cause of conflict. Francis (2012: 5) concludes: ‘in effect, though peacebuilding has a normative orientation i.e. reconstructing a secure, peaceful and developed society, it is a largely value-laden project that apportions disproportionate powers to those who prescribe, fund and implement peacebuilding programmes’. The overall goals of peacebuilding will be achieved, according to Jeong (2005: 13), by ‘reconstruction and reconciliation that are geared not only toward changing behaviour and perceptions but also toward social and institutional structures that can be mobilised to prevent future conflict’. Hamber and Kelly (2005: 38) see reconciliation as a core component of peacebuilding, which they define as the ‘process of addressing conflictual and fractured relationships and this includes a range of activities. It is a voluntary act that cannot be imposed’.

Critics, on the other hand, see significant limitations in placing reconciliation at the heart of peacebuilding in Northern Ireland. Such an approach, they argue, is concerned with relationship-building over the challenge function, ignores power differentials between those being reconciled and neglects the role of the state in creating or maintaining divisions (McVeigh 2002; Lamb 2010). McEvoy et al. (2006: 82), for example, argue that a successful peace process in Northern Ireland has been achieved ‘which effectively side-lined a significant reconciliation industry’ because reconciliation became synonymous with healing relations between two religious blocs (the ‘two tribes’ approach) without acknowledging the role of the British state in the conflict. Hence the term ‘reconciliation’ was seen as a ‘dirty word’ which was used and abused, which was ‘anti-ex-combatant, weak in rights’ protection, and geared towards creating an imagined middle ground’ (McEvoy et al. 2006: 98).

Models of Peacebuilding

Several scholars have offered models of peacebuilding which allow us to conceptualise how different approaches might provide a better understanding of various policy and practice interventions. We discuss these in no particular order. Lederach: Lederach (1997) makes three broad observations about peacebuilding in deeply divided societies. First, he argues, there is an over-emphasis on short-term tasks which are often separated from the longer-ranging goals of social change necessary to sustain any macro-political achievements made. Each political crisis or incident becomes the focus of attention rather than a strategic vision of where the divided society is going. Examples here could include problems which arose over decommissioning paramilitary arms in Northern Ireland, the political and legal ramifications of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s findings in South Africa and prisoner releases in Israel (Knox and Quirk 2000).

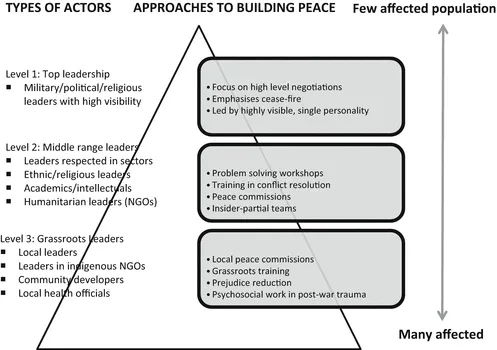

Second, Lederach argues there is a hierarchical approach to peacebuilding instead of an organic approach. He presents this as a three-level pyramid (see Fig.

1.1). At the top level, politicians, the military/police and appointed officials/advisors engage in high-level negotiations with the aim of reaching some kind of political ‘solution’ or compromise. At the middle level there is input from sectoral leaders, e.g. the business community, trade unions, religious leaders, academics and think tanks. At grass-roots level, NGOs, the voluntary and community sectors and local activists are involved. Lederach makes two observations about the pyramid population. First, the grass-roots level is the tier at which many of the symptoms of conflict are manifest—social and economic insecurity, political and cultural discrimination and human rights violation—but the lines of ethno-national conflict are drawn vertically rather than horizontally through the pyramid. In other words, the three levels in the model are not pitted against one another; conflict is cross-cutting. Second, there are two inverse relationships in a conflict setting. Those at the top of the pyramid have the greatest capacity to influence the wider peacebuilding process but are least likely to be affected by its consequences on a day-to-day basis. Those located at the bottom of the pyramid, on the other hand, will be directly influenced by the outcomes of macro-developments but will have limited access to the decision-making process and a narrower view of the wider agenda, which may demand bargaining and compromise (Lederach

1997: 43). Lederach argues: ‘my basic thesis would be that no one level is capable of delivering and sustaining peace on its own. We need to recognise the interdependence of people and activities across all levels of this pyramid’ (Lederach

1996: 45). In short, much of the activity is focused on top-level leaders and the macro-level political activities in which they are engaged.

This has significant consequences in terms of the pace of change experienced across the three levels. The peace process can be seen as moving simultaneously too slowly or rapidly. It will be too slow for those whose expectations have been raised by the possibility of peace, according to Lederach, and too rapid for those who feel they have conceded too much and received too little. An example here could be unionists in the Northern Ireland peace process, who now claim to have experienced a significant loss of their culture, rights and socio-economic status. Lederach concludes that the top-level official process is incapable of delivering on its own and that there is a need for an organic approach which treats peacebuilding as a web of interdependent activities and people across all three levels, rather than a hierarchical model.

The third component of the model poses the question: how do divided societies move from transition to transformation and ultimately reconciliation? Here Lederach argues that there are important political changes which are integral to the process of transition in divided societies, referred to as ‘the technical or task oriented’ components of any negotiated settlement. While these political changes are necessary if reconciliation is to be achieved, moving beyond transition to transformation requires a more comprehensive approach involving social, economic, socio-psychological and spiritual changes. Only then can new relationships be built based upon a willingness to acknowledge truth and past injustices and an openness to both offer and accept forgiveness. Lederach concludes:

Peacebuilding requires a vision of relationship. Stated bluntly, if there is no capacity to imagine the canvas of mutual relationships and situate oneself as part of that historic and ever-evolving web, peacebuilding collapses. The centrality of relationship provides the context and potential for breaking violence, for it brings people into the pregnant moments of the moral imagination: the space of recognition that ultimately the quality of our life is dependent on the quality of life of others. (Lederach 2005: 35)

Galtung (

1969,

1996): is widely recognised as having made a seminal contribution to the field of peacebuilding. He makes the distinction between three forms of violence: direct violence, structural or indirect violence and cultural violence. He defines direct violence as taking a verbal and physical form, and as causing harm to the body, mind and spirit. Structural violence takes various forms: political, repressive, economic and exploitative. Cultural violence involves religion, law and ideology, language, art and so on. Galtung delineates between ‘negative’ and ‘positive’ peace. The former is the absence of violence, whereas the latter requires peacebuilders to address the multiple manifestations of structural and cultural violence. Demmers (

2012: 57) explains structural violence further, as the processes and mechanisms that prevent people from achieving their potential: ‘the silent violence of poverty, low education, poor health and, in general, low life expectancy inherent in the way societies are organised’. This has a particular resonance in the 1960s civil rights movement within Northern Ireland, which highlighted the hegemony of unionism, inequalities suffered by Catholics in securing jobs, housing and economic prosperity and precipitated ‘the troubles’ (McGarry and O’Leary

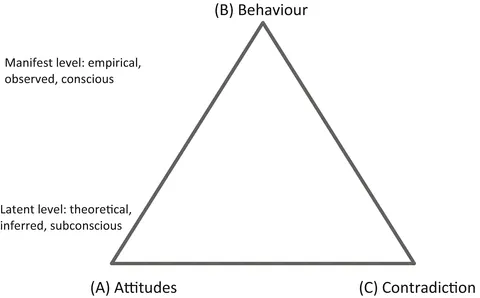

1995). Galtung described conflict in the form of a triangle comprising attitudes (A), behaviour (B) and (C) contradiction (see Fig.

1.2). All three are required for fully fledged conflict. The manifest, observable or conscious aspects of conflict are identified by B for behaviour (violence and discrimination); and, the latent, theoretical, inferred or subconscious elements are identified by A for attitudes/assumptions (fear, prejudice) and C for contradiction. Galtung (

1996: 70) describes the latter thus: ‘deep inside every conflict lies a contradiction, something standing in the way of something else, a problem in other words’.

Demmers (2012: 75) explains the intercon...