This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The book shows the fundaments of the shadow banking system and its entities, operations and risks. Focusing on the regulatory aspects, it provides an original view that is able to demonstrate that the lack of supervision is a market failure.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Shadow Banking System by Valerio Lemma in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Corporate Finance. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

General Observations

Under a regulatory approach, this chapter will address the questions about the definition of the shadow banking system and its basic elements.

First the boundaries of this system will be defined; then I focus my attention on the definitions provided by international bodies: the Financial Stability Board (FSB), the International Money Fund (IMF), the World Bank—and national authorities: the Federal Reserve System (FED), the Bank of England, the Bank of India, the Bank of China, the Bank of Italy—from both a monetary and supervisory point of view.

The chapter will go on to explain the differences between the shadow banking operations and the illegal practices (i.e. money laundering, tax evasion, etc.) in order to understand the benefits of this market-based form of credit intermediation.

1.1 The identification of the phenomenon

In countries with a high rate of financialization, the legal systems do not provide for a “fundamental rule” that defines the concept of the shadow banking system. The shadow banking system is, therefore, not considered as a whole.1 Specifically, it will be observed that the European and national regulations are considering this phenomenon with regard to its empirical manifestation, arising from the choice of private individuals to let their capital circulate outside of a regulated financial market or without the involvement of a credit institution (as the banking system is defined by art. 3 of Directive 2013/36/EU).

Consequently, it is necessary to identify the elements that lay at the foundation of this choice, but without researching—within the shadow banking system—an “exchange center” towards which the open market operations converge. Here I move away from the assumption that the present situation does not reflect the known concepts of “regulated market,” “multilateral trading facilities” (MTF), and “organized trading facility” (OTF), used by Directive 2014/65/EU, to identify “trading venues” that must comply with the requirements of European law (and, therefore, the provisions of the European financial supervision system).2

Moreover, the financial transactions that are not referable to a single country and, therefore, to a specific system of supervision will be taken into account. These transactions are not included even in the perimeter of the new surveillance mechanisms that go beyond national boundaries (in the forms, first, of the Sevif and, then, of the European Banking Union). Neither of these mechanisms seems sufficient to encompass the phenomenon in its entirety. It is, therefore, penalizing the absence of a “global supervision” that extends its scope to the global financial network that crosses the planet (and, therefore, exceeds the obvious territorial limitations of the sovereign authorities).

Therefore, the financial markets demonstrate the existence of a network of legal relations and the absence of an authoritative system of regulation and control (dedicated to them). These conditions are sufficient to identify the core foundation of the shadow banking system. This is why specific elements are identified to support a legal reflection about future actions—useful or necessary—in order to ensure that the freedom of the shadow system should not damage the public welfare.

It appears, however, necessary to keep in mind that regulatory actions could achieve inefficient results if the cost of the supervision is more onerous of its benefits. In other cases, the shadow operations could avoid general interests and, then, certain specific prohibitions are required (even if they are not efficient).

That said, it is useful to bear in mind that, in economic terms, there is a functional definition of the shadow banking system, which is able to allow a measurement of its quantitative importance. And, indeed, any operation executed out of any supervised trading venues can be accounted to the shadow banking system. This is, therefore, part of the financial global system, which, to date, allows the movement of capital across the world, through the channels of an integrated global network, dynamic and innovative, formed by interactive components consisting of: intermediaries, securities (products/instruments), markets, derivatives, regulation and supervision, payment, clearing, and settlement systems.3

In addition, the relationship between the economic importance of the phenomenon under observation and its multilateral nature is especially relevant; because it is based on a systematic meeting of interests (which are referable to several subjects, some of them in surplus and others in deficit of capital). This is, in fact, a characteristic trait, which excludes from the scope of our investigation operations that are carried out on a bilateral basis (in reciprocal and symmetrical modes).

Both of these elements are implicitly implied by the term itself— “shadow system”—where the assumption is clear that the systematic character of the operations shall be realized in terms of opacity. The word “banking,” then, suggests the selection of only those operations that allow the collection of resources for the start of any credit business. That said, it is necessary to dwell on the meaning attributed to the banking qualification for such a shadow system.

The use of the term banking, in fact, reflects the specificity of the interests that are part of the system under consideration. This also highlights the nature of the goals of price stability, savings protection, and credit control, which conform to the legal requirements of countries with advanced economies. Moreover, as a result of the recent financial crisis, these goals influence the evolutionary process of European law, which, as we shall see, is now characterized by new common forms of supervision (and prudential vigilance) on the banking and financial sector—that is, the European System of Financial Supervision (ESFS) and the European Banking Union (EBU).4

In light of the foregoing, we can understand that the banking qualification of this intermediation process of capital can be considered both as a constitutive element of the system and a peculiar configuration of its operations—which lets subjects with surplus resources enter into a relationship with others that, to meet their needs, are willing to remunerate the temporary transfer). This applies, in particular, to the various operations that are able to overcome the barriers to the meeting—in traditional ways—of demand and supply of capital (referring to the asynchrony of the deadlines, the asymmetry of the risk profiles, or other impediments, including ones of geopolitical nature.

In this context, a complete definition of the shadow banking system must take into account the subjects not included in the scope of government supervision and the operations aimed at achieving a (regular, synthetic, or derivative) circulation of capital outside of any regulated market, without the involvement of supervised intermediaries.

In brief, it can be said that we are not considering the operations based on organic relations (and, therefore, those made within a single subjective entity) or intra-group (or rather, within the same socio-economic unit). The same can be said with regard to other activities that do not comply with an intermediary logic, but pursue speculative goals. In particular, we cannot include in the shadow banking system any operation or action if it takes resources from the economic system, instead of intermediating them (and then does not multiply them through rapid circulation). There is no doubt, in fact, that these operations and activities—while they should not be regarded as degenerative—are predatory towards the goals of social utility that lie at the root of every balanced and democratic system.

The aforementioned considerations lead to the reconnection of shadow banking to the effects of financial liberalization, which do not prevent economic operators (i.e. companies and investors) from negotiating with subjects that intermediate capital without applying the safeguards provided by supervision.

Addressing the analysis of the phenomenon from this perspective, it appears possible to highlight the importance of the operations of securitization and the wholesale funding, as well as other methods aimed at increasing the raising of capital:

•asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP) conduits;

•structured investment vehicles (SIVs);

•credit hedge funds;

•money market mutual funds;

•securities lenders;

•limited-purpose finance companies (LPFCs); and

•government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs).

The same has to be said for the relevance of the:

•government-sponsored shadow banking subsystem;

•internal shadow banking subsystem; and

•external shadow banking subsystem.

Therefore, this is a complex phenomenon in which—as shall be shown in the following chapters—there are several structures and subsystems. These denote original profiles, which influence the individuals’ mutual business relations. Nonetheless, this is a system that is composed by multiple exchange relationships—bilateral and multilateral—all interconnected (and, therefore, included in the definition of shadow banking system).

The consequence is an independence of the shadow banking system from the traditional economic structure. This is exactly the foundation for a rising trend and, then, for a new system of private relations (where the abovementioned structures do exist only if the individual chooses to link the credit intermediation process with them). Hence the power of the structure of the single transaction over the whole system, since the latter can be considered as the result of free market relations.

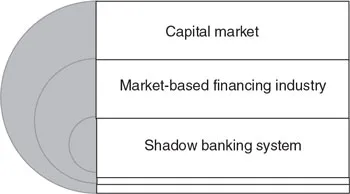

Table 1.1 The phenomenon in the capital market

This suggests that shadow banking can be also a discontinuous set of heterogeneous processes, employed by several individuals; resulting in an informal coordination of financial structures (see Table 1.1).

There is, in other words, an accumulation of “entities and operations,” which tend to constitute a system. This corresponds to the intensity of the relationship between the subjects engaged in it, determining a sort of cohesion that may cause significant systemic effects.

This leads to the conclusion that: in the shadow banking system, prima facie, it is possible to relate the opacity of its qualification (i.e. the term shadow) to the collateral position that it occupies (in relation to the regulated markets subject to government supervision). It is, at least in part, determined as a result of a specific choice made by the operators (and, that is, by the exclusion of certain operations from the burden of the legal rules and safeguards of public supervision). However, it can be also a consequence of certain dysfunctions and delays in the regulatory process, with obvious implications—in terms of accountability—for the authorities who fail to renew their (economically obsolete) practices and standards.

1.2 The traditional definitions of the shadow banking system: the guidelines of the FSB and the statement of the G20

Priority must be given to the economic analyses that, in monitoring the shadow banking system, have identified its essence in the “credit intermediation involving entities and activities outside the regular banking system.”5 These analyses allow the interpreter to identify a particular form of market-based financing, which accounts, in quantitative terms, for the growing economic importance of the transactions that develop through it and, in terms of quality, for its foreignness to the paradigms of prudential supervision and capital adequacy.

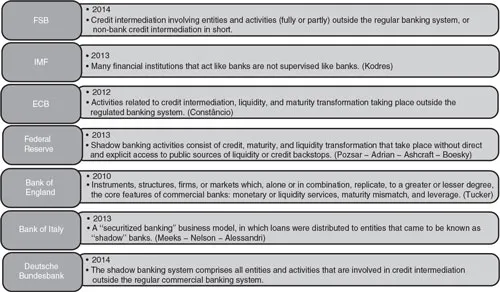

The FSB formulated the abovementioned definition in residual terms—in comparison to the boundaries of the traditional banking system.6 This means that the FSB did not highlight the constitutive elements of the phenomenon. And indeed, it does not address the benefits brought—to the real economy—by this alternative credit intermediation (i.e. placed outside of the banking channels), nor does it indicate explicitly that this form of intermediation can also have risk– reward parameters that are not compatible with the system of prudential supervision (see Table 1.2).

Hence, the analysis starts from the lack of clarification about the possibility that—within the shadow banking system—it will generate (and will proliferate) systemic risks arising from: (i) the transformation of the maturity, (ii) the exploitation of leverage, (iii) the frequency of the relationship between the industry operators, and (iv) the inefficiency of the risk transfer mechanisms.

Table 1.2 Definitions

In 2014, the FSB presented new results—in its fourth annual monitoring exercise using end-2013 data—showing the danger that excessive competition may turn the terms of credit intermediation against certain operators. Moreover, the FSB highlighted that its new exercise will influence future monitoring reports, understanding that the “narrowing down approach” shall leverage on the new information sharing standards introduced by EU rules (on markets, financial firms, and credit institutions that operates with shadow banking entities).

This exercise may be criticized for the apparent indifference to the new data requirements introduced, at European level, by Emir Regulation (no. 648 of 2012). However, there is an awareness that the realism of the FSB’s Workstream on Other Shadow Banking Entities (WS3) is much preferable to the confused “first-run data accounting” of the new “trade-repositories” (which centrally collect and maintain the records of derivatives, under the direct supervision of ESMA).7

Consequently, it is easy to understand the need for a more accurate monitoring intervention (b...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables

- Introduction

- 1. General Observations

- 2. The Shadow Banking System as an Alternative Source of Liquidity

- 3. Shadow Banking Entities

- 4. Shadow Business of Banks, Insurance Companies, and Pension Funds

- 5. Shadow Banking Operations

- 6. Non-Standard Operations in the Shadow Banking System

- 7. Shadow Banking Risks and Key Vulnerabilities

- 8. The Shadow Banking System and the Need for Supervision

- Conclusions

- Notes

- Index