This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This study offers an analysis of the UK's current economic policy options and a plan for improving life for ordinary citizens via a sensible and realistic understanding of governments' limited ability to manage economic performance. It provides a manifesto which political parties could immediately adopt to make life better for all.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access National Policy in a Global Economy by I. Budge,S. Birch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & European Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

A British Economy? Boxing with Shadows

Abstract: This chapter argues that the notion of a ‘British economy’ is a myth in today’s globalized world. This has considerable implications for governments’ approaches to dealing with economic crisis. The underlying problems with the classic ‘austerity’ and Keynesian approaches will be elaborated. The focus will be mainly on Britain, though there will also be references to austerity measures implemented elsewhere.

Keywords: austerity politics; British economy; economic crisis; globalization; Keynesianism

Budge, Ian with Sarah Birch. National Policy in a Global Economy: How Government Can Improve Living Standards and Balance the Books. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. DOI: 10.1057/9781137473059.0003.

In the Non-Existent Knight, a moral tale by Italo Calvino, the Emperor Charlemagne is reviewing his knights, flicking up their visors to see what condition they are in after an exhausting campaign. One suit of armour has nobody inside. ‘Good God man, how do you keep going?’ cries the Emperor. ‘Persistence and faith in our holy cause.’

The same could be said of the British economy. It doesn’t really exist but economists persist in talking as if it does, and politicians share their faith in it. There are endless plans for its revitalization. In party pledges and programmes it takes the central part, with promises to generate more wealth from a recovery that will create jobs for everyone and pay for everything else – if only we will put up with cuts and austerity (or, alternatively, inflation) for some time yet. As another poet remarked, ‘I see the bridle and the spurs of course – but where’s the bloody horse?’

None of this is to deny that there are economic activities going on in Britain which provide most of the population with a living and generate the revenues which pay for government and for public goods and services. Of course there are. We would be flying in the face of reality to deny it. But do such activities cohere with each other and add up to an economy in the sense of a set of activities and enterprises which have more to do with each other than they do with ones located outside their boundaries? If they do not – as we will argue is clearly the case in Britain and most contemporary states – how can the British government claim to steer them and plan for their future as a coherent autonomous entity rather than a more or less random agglomeration which does not respond consistently to government signals? If the oil industry has more links with Norway or Arabia than with Midlands car manufacturing; if London banks make more money from speculating in America than in Europe – let alone Britain; if agriculture is shaped more by the Common Agricultural Policy of the European Union (EU) than by British regulation, where are the communalities that bind all these activities (and many more) together, other than the fact that they all happen to be located in Britain (but spread also over a lot of other places)? This lack of economic cohesion is not of course peculiar to Britain. It is true of most countries in the world. Only in a few large ones – the United States and perhaps India – could the economic enterprises located there be said to have more to do with each other than with the rest of the world. Even mighty exporters like China and Japan have by that very fact made themselves dependent on distribution chains and sales elsewhere and so rely on other countries’ efficiency and prosperity for their own economic health.

The major factor unifying so-called national economies is paradoxically a political one: they share the same overall government. This is usually the largest single economic actor within its own territory, and it makes some rules for the others. But even that role is being eroded by international agreements and treaties.

The most realistic definition of a so-called national economy is that it is the national governments’ potential tax base, from which it can draw the revenues to finance its other activities – wars and administration but also some public services (all themselves, of course, ‘economic activities’ of some kind). All this might seem academic. What does it matter to ordinary folk how you define an economy? What does matter is that there are decent jobs and wages and reasonable living conditions. So long as the enterprises and firms in a country provide these, who cares whether they have more to do with each other than with other parts of a corporation located abroad?

We shall argue that it does matter – that it makes a big difference to our personal well-being if national policy-makers think they can make economic plans untrammelled by external developments and events and demand national sacrifices for doing so. The idea of an autonomous national economy which they can shape at will clearly encourages reckless government behaviour. Dashes for growth and grandiose plans for expansion are too often succeeded by austerity and service cuts to ‘rebalance the books’ – itself a somewhat dubious concept highly shaped by arbitrary and obscure accounting conventions (Sikka, 2010). Our sad experience of so many development plans which came unstuck has alas made few dents in governments’ endless optimism. In this they are encouraged by their economic gurus, neo-liberal or Keynesian, who generally claim to have an economic panacea which will – eventually – work within the national context.

Unfortunately these ambitious economic plans usually come at the cost of neglecting the other things governments could do to improve life nationally. In particular, health, education, culture, sports and environment often take a beating as they are viewed in purely economic terms or as unnecessary fripperies in the context of the latest wheeze for national economic growth. ‘Paradise postponed’ should be the notice on most chancellors’ doors.

We should move away from government-led economic development. In a country like Britain economic development has already arrived and will take care of itself. In any case governments have demonstrated quite clearly that they cannot deliver it – though they rarely fail to claim the credit for any surge in activity due, for example, to the discovery of oil, or the irresponsible actions of banks, while blaming others for downturns.

What national governments should be doing instead is what does lie within their power to improve things – charge efficiently for their business services and then spend adequately on the general quality of life for their citizens. They do have control over their own territory. But they often neglect service improvements in the here and now to pursue some economic vision for the distant future.

In the following chapters we will provide arguments and evidence to support our thesis, ending with a practical plan of action which focuses much of the political debate which has taken place since the world economic collapse of 2008. We start by expanding on what we have said here, beginning with a diagnosis of the thinking of professional economists which has encouraged national governments to go up the blind alley of seeking to promote economic growth.

Defining economies politically: a basic flaw in macroeconomic analysis

How would we react if lawyers insisted on studying ‘Iberian’ law, ignoring the division of the peninsula into Spain and Portugal, with separate Parliaments, law codes and courts? Or if they claimed that Russian law operated differently in the European area and in Siberia, ignoring the fact that the Russian Federation covers both? We would clearly feel there was something wrong if lawyers took natural geographic features as defining their basic unit of analysis, rather than as an area under one sovereign legislative authority.

Why therefore should we accept economists taking politically defined entities – states – as their basic unit rather than one which makes sense in economic terms? As we have suggested, taking an economically rather than a politically defined unit for analysis would lead to a macro-economic focus on clusters of economic activities which actually belonged together, in the sense that their interactions were more focused on each other than on outside activity. Economies defined in this way would indeed be largely autonomous entities whose dynamics – their growth and contraction – would be driven largely by internal developments rather than by events elsewhere. Such internal developments might of course include government interventions and fiscal policy, which could have a considerable effect if the economy were largely self-contained.

Few economies of course are like Robinson Crusoe on his island, totally self-contained. However clusters with more transactions taking place internally would approximate this favoured example. The ‘national’ economies usually referred to actually lack any clear economic boundary, so that in practice their economic activity is just a local manifestation of a larger economy whose dynamics are determined by wider forces than those operating locally.

Most, if not all, national economies are now edging closer to the latter than to the former situation, that is, their expansions and contractions are driven to a great extent by external forces. True, so-called gravity and border effects do mean that most trade takes place within states or with close neighbours (Anderson and Wincoop, 2004; Helliwell, 1998). Yet there is evidence that this effect has declined over time (Parsley and Wei, 2001). Certainly most goods and services bought and sold by UK economic actors involve domestic trade only – two-thirds in fact. However this also implies that one-third does not. In 2012, 34 per cent of all goods and services consumed within the United Kingdom came from abroad, and 32 per cent of all the goods and services produced in the United Kingdom were exported.1 These are the more dynamic flows more directly affecting internal economic developments, for example, supermarkets searching for ever cheaper food from abroad. Only in the movement of labour do cross-border restrictions and cultural impediments significantly limit cross-border flows. Even these factors have diminished considerably in recent years within the European Union.

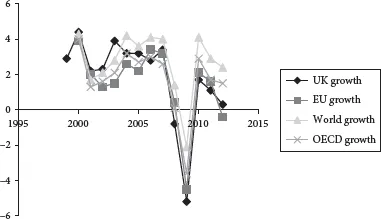

The ‘new institutionalist’ political economy, which became popular in the 1990s, does put emphasis on the role of domestic institutions in structuring economic activity (e.g., Coase, 1998; North, 1990; Ostrom, 2005). However evidence suggests that the relevance of national institutions is overplayed. Figure 1.1 demonstrates the extent to which economic growth in the United Kingdom tracks developments elsewhere in the world, and particularly among comparators such as the OECD and EU member states.

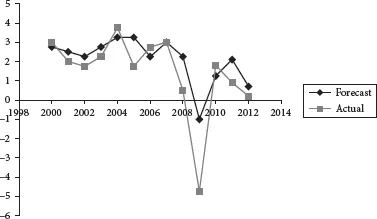

It is telling that growth rates in other parts of the world are better predictors of what happens in the UK economy than are official predictions made by UK state agencies whose task it is to forecast economic developments. Figure 1.2 demonstrates the frequent discrepancy between economic forecasts and resulting change over recent years. The forecast is almost always higher than the reality, possibly owing to political pressures.

FIGURE 1.1 UK growth is global growth

Note: The data in this table are based on the ‘GDP growth (annual %)’ indicator from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators dataset at www.worldbank.org. This measure reflects the ‘annual percentage growth rate of GDP at market prices based on constant local currency. Aggregates are based on constant 2005 U.S. dollars’.

FIGURE 1.2 Forecast and actual growth in the United Kingdom, 2000–12

Note: These data were obtained from the following sources: forecasts are those made by the Treasury and reported in pre-Budget Reports/Autumn Statements (http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20100407010852/http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/prebud_pbr05_index.htm); actual growth rates are those reported by the Treasury and the Office for Budget Responsibility (http://budgetresponsibility.org.uk/category/topics/economic-forecasts/).

It is clear from these figures that the efforts of domestic policy-makers to steer economic development in the United Kingdom are often unsuccessful. Actual growth rates are determined largely by what happens outside the borders of the United Kingdom. The pattern of correlation coefficients between these sets of figures backs up this claim. There is a coefficient of .93 between UK and EU growth rates over this period and a coefficient of .94 between UK growth and OECD growth.2 The correlation between UK growth and world growth is .89. The correlation coefficient between Treasury predictions for the next year and actual growth for that year is, at .86, lower than all of these. In other words we would do better basing ourselves on world growth to anticipate what is going to happen in the United Kingdom than on government actions and aspirations. This provides strong evidence that the efforts of UK leaders to steer British economic activity have less influence on economic outcomes than do global economic forces, and especially economic forces from the United Kingdom’s closest trading partners.

This new reality has two implications: (a) simulations and predictions of the way the country will develop economically have to have accurate information about the impact that wider forces have on internal activities – not just on those in closely linked sectors but in each of the diverse sectors represented in a given territory. We do not simply need to know about how Chinese imports will impact generally on Britain but what impact they will have, for example, on pharmaceuticals or sales of toys, heavy machinery or furniture-making. The cruder and less sensitive this type of information is, the less accurate will be our predictions of what is going to happen in the relevant area. Quite apart from prediction, we may not even be able to see what is happening now, in the necessary detail. (b) This in turn means that governments have too little information about what is actually happening on the ground, economically speaking, in their own territory. They have little basis for informed action, therefore, other than crude general ideas, for example, that pumping out more money will encourage sales. As seen so often in Britain, however, these will often be sales of foreign imports and so do little to stimulate home employment, outside the distributor companies. So the intended effects – stimulating growth and jobs – tend to materialize only in a muted way, if at all. Medium-term effects can be perverse, resulting in an overall loss of jobs in small firms making these products in Britain.

The wider problem, however, is that by talking in terms of a national economy (by implication one with a largely internal, autonomous dynamic) many economists encourage governments to think they can produce intended and significant effects. The reality is of course that they rarely can do so. They may be the big fish in the national pond – though even there they are not typically the most dynamic or adept economic actors. But they are small fish indeed in Europe or in the world.

Why do most economists not base themselves on a more realistic unit of analysis to which their theories would apply – that is, an economy driven by its own internal dynamics in a relatively predictable way rather than one shaken by the external forces which predominate in its workings? In the presence of globalization this might imply working at the world level, given that every area is now so interdependent with others. But if this is the only way to generate a realistic macro-model, whose predictions can then be applied to different countries depending on the particular mix of economic activities going on there – why not?

The answer may lie in a certain professional inertia. National governments are the major bodies collecting statistics on economic activities, with international bodies like the OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) drawing on them. OECD countries have certain common standards but many outside countries do not. Non-comparable standards in classifying trade-flows and revenues contribute to notorious problems, like the ‘black hole’ between world imports and exports. Figures for those should logically equal each other. But often they do not, leading one to doubt the accuracy of the whole set of statistics on which they are based (Economist, 2013a).

National statistics, particularly for developed countries, are thus the most accurate and convenient to use. So they are used. But they relate to a territorially defined, politically delineated entity not to one which necessarily makes sense in terms of economics. What can be measured is studied (and therefore is assumed to exist). What cannot be measured is not studied and by extension does not exist – at any rate in the minds of most economists and politicians.

What emerges from this situation is a vicious circle. Governments keep records, for the most part, for administrative purposes. Imports, exports, incomes, profits are all crucial information about their tax base and what they can expect in the way of the revenues which they can extract as taxes from economi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 A British Economy? Boxing with Shadows

- 2 Globalization and Its Effects

- 3 What National Governments Can and Cant Do Well

- 4 Providing Citizen Support

- 5 Paying for Support

- 6 Focusing on Action: A Model Manifesto

- 7 Putting Policies into Practice

- Bibliography

- Index