![]()

Part I

The Malthus–Ricardo Debate

1

The Malthus–Ricardo Debate on General Glut and Secular Stagnation

Abstract: Adam Smith contends that a market economy gravitates to full employment and that its growth is limited only by the rate of capital accumulation and the cost of foodstuffs. JB Say asserts that demand is determined by supply; that people produce goods to obtain the means to make offerings to purchase the goods they desire. Thomas Malthus contends that capitalists do not produce goods in order to consume; they produce to accumulate wealth, which creates a deficiency in demand. Too high a rate of saving will render demand insufficient to support full employment. David Ricardo defends Adam Smith’s position in his debate with Malthus. He and Malthus agree that the attainment of full employment hinges on whether people produce more than they plan to spend.

Keywords: Adam Smith; aggregate demand; General Glut; Law of Markets; Malthus; Ricardo

Aronoff, Daniel. A Theory of Accumulation and Secular Stagnation: A Malthusian Approach to Understanding a Contemporary Malaise. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016. DOI: 10.1057/9781137562210.0005.

We have seen the powers of production, to whatever extent they may exist, are not alone sufficient to secure the creation of a proportionate degree of wealth. Something else seems to be necessary in order to call these powers fully into action. This is an effectual and unchecked demand for all that is produced . . . 1

It is unquestionably true that wealth produces wants; but it is a still more important truth that wants produce wealth.

—Thomas R. Malthus2

Virtue itself turns to vice being misapplied/And vice, sometimes by action dignified.

—William Shakespeare3

1Malthus’s addition to Adam Smith’s causes of the wealth of nations

In The Wealth of Nations (1776) Adam Smith enquires into the sources of economic prosperity and growth. He identifies two factors that fundamentally determine the prosperity and rate of growth of an economy. One factor is the degree to which the rule of law prevails—both the legal framework and obedience to it—which secures property rights and the sanctity of contracts necessary to promote the division of labor and the incentive to make capital investments. Smith describes a market economy as a self-regulating system governed by underlying forces generating supply and demand for each good. Participants in the market—whom I call “agents”—are led as if by “an invisible hand” to establish prices and a pattern of production that balance supply and demand for each good, and to effectuate a division of labor that expands output beyond what it would be if agents did not trade. Implicit in Smith’s conceptualization is that a market economy tends to operate at full employment, since he assumes that human wants are insatiable which implies there is a profit to be earned by delivering (or transforming) an idle resource to someone who values it.4 An economy in which planned (or notional) supply and demand for each good is balanced and all resources are utilized is in a state of “full employment equilibrium.”5 The other factor Smith identifies as contributing to prosperity and growth is the accumulation of capital—which requires that agents save and invest a portion of their income. Capital augments the productivity of labor, which expands potential output.6

According to Smith the rate of saving—for a given level of enforcement of property rights—is determined by the habit of parsimony, which is similar to what contemporary economists call the rate of time preference.7 Smith contends that all planned saving is invested in capital:

It follows that the more parsimonious citizens are, the greater will be the volume of capital accumulation and the rate of growth.

Smith believes that the habit of parsimony is, for the most part, a matter of innate character; and that the enterprises controlled by men of parsimonious habits are more likely to thrive and grow.11

The assumption that a market economy gravitates to full employment equilibrium implies that the level and the rate of growth of output is determined by the size of the labor force, the state of technology (which determines the output—of foodstuffs and manufactured goods—achievable from a given combination of labor and capital), and the rate of saving. Those are the forces that determine potential output, and the gravitational pull toward full employment ensures that the economy will tend to operate at its potential output. Therefore, though demand plays a role in determining prices and production for individual goods—and consequently the allocation of resources—demand does not affect the aggregate level of output in Smith’s system. This insight is more clearly articulated in the generation following Smith, by J. B. Say and James Mill, in the proposition that supply creates demand, since goods are required to be offered in exchange for goods and each individual produces only because of, and to the extent of, his demand for other goods.13

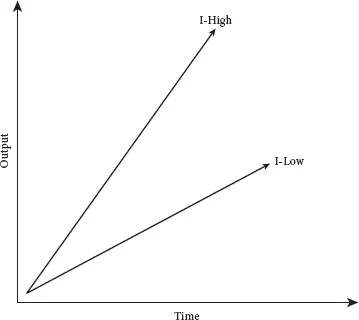

The growth of output of a market economy, as described by Adam Smith, is depicted in Figure 1.1. The horizontal axis represents time and the vertical axis represents the value of aggregate output at some base price index. Line I-high depicts the growth of output when saving (and investment) is “high,” and line I-low when saving is “low.” I-high lies above I-low because, as Smith explains, an economy becomes wealthier over time, the higher its rate of capital accumulation.

In Book II of the second edition of his Principles of Political Economy (1836), Malthus begins his enquiry into the determinants of the wealth of nations by asking why countries that are similar in respect of the two fundamental causal factors identified by Adam Smith nevertheless appear to differ in their levels of per capita output and rates of growth.

FIGURE 1.1 The relation between investment and output over time in Adam Smith’s model

Malthus does not question Smith’s view that capital investment is required to grow an economy. But he believes Smith fails to grasp that aggregate demand could exert an independent influence on employment, investment, and the growth of the economy over time.

In treating aggregate demand as an independent causal factor, Malthus attempts to augment the Smithian paradigm by incorporating an explanatory variable he believes to have been overlooked. But the implication of positing aggregate demand as a causal factor in determining the state of the economy constitutes a radical departure from Smith’s framework. It is difficult to convey just how upsetting Malthus’s approach must have been on several different levels. The very concept of aggregate demand influencing employment contradicts the assumption that a market economy tends to operate a full employment.17 It gives rise to the possibility that the invisible hand may leave resources or productive potential unused. It places the precepts of Christian morality in opposition to the necessities of material well-being. Many considered it blasphemy to assert that parsimony and thrift, by reducing aggregate demand, could force working men into unemployment, while prodigality and gluttony could restore their fortunes. This is the opposite of what Smith contended:

Malthus’s questioning of the benefits of parsimony and his belief in the importance of aggregate demand has antecedents. Bernard Mandeville, who was among the first social thinkers to realize the potential for divergence between individual motives and societal outcomes, wrote in the Fable of the Bees (1732) of how the reprobate traits of prodigality and avarice were sometimes beneficial to society, whereas frugality could bring on depression. Mandeville wrote of the unemploy...