eBook - ePub

Debt, Democracy and the Welfare State

Are Modern Democracies Living on Borrowed Time and Money?

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Debt, Democracy and the Welfare State

Are Modern Democracies Living on Borrowed Time and Money?

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Why is it that government debt in the developed world has risen to world war proportions in a time of peace? This can largely be attributed to governments maintaining welfare expenditures beyond what tax revenues allow. But will these governments refrain from doing what is necessary for economic growth for fear of losing their electorate?

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Debt, Democracy and the Welfare State by R. Hannesson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Économie & Politique économique. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ÉconomieSubtopic

Politique économique1

The Rising Tide of Debt

Abstract: In this chapter, the development of government debt in the traditional OECD member states since the Second World War is traced. Some countries were saddled with a large debt as a legacy of the war, but their debt as percent of GDP gradually fell until the mid-1970s. After the energy crisis of 1973 the debt began to rise in most countries. In many countries the debt has continued to rise ever since, almost without interruption, and in some countries it has reached world war proportions. Some countries have managed to reverse the debt accumulation, all of them relatively small.

Hannesson, Rögnvaldur. Debt, Democracy and the Welfare State: Are Modern Democracies Living on Borrowed Time and Money? Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. DOI: 10.1057/9781137532008.0003.

Not so long ago, government debt emerged as a topic of actuality. A generation ago it was hardly even mentioned in textbooks on economics or even public finance. There were, of course, the pathological cases of the German, Austrian and Hungarian hyperinflations that happened in the years after the First World War when governments borrowed money from their central bank to pay for their deficits, essentially printing money (even in a literary sense1). But for governments borrowing money from the capital markets, and perhaps a little bit from their central bank, the topic seemed hardly worthy of attention, and certainly not the question whether they could go on doing so and whether their lenders could be confident in getting their money back.

It was not always thus. European monarchs in times past were notorious for defaulting on their borrowings, in particular King Charles of Spain. Lenders had few recourses to get their money back from such borrowers and so became wary of lending to kings. Some historians think that the British Empire owed its emergence and its victory over Napoleon to its superior finances and a history of no defaults, even if that history was relatively recent (since the Glorious Revolution of 1688).2 Its indebtedness after the Napoleonic wars is supposed to have reached an all time high, in comparison to its national product, even if such a comparison for times well over a hundred years before anything like national accounting was invented seems courageous. But for someone growing up in the Western world after the Second World War, concerns about government debt seem a recent phenomenon.

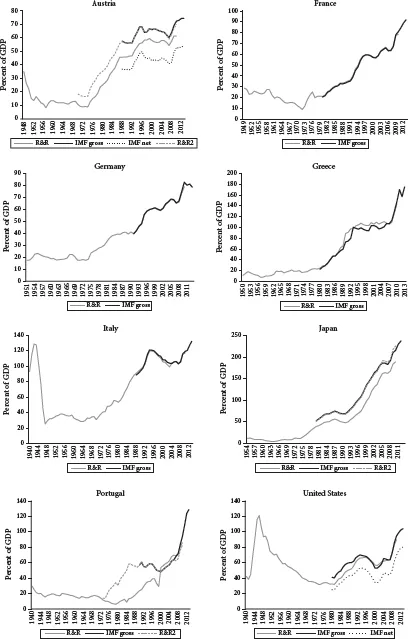

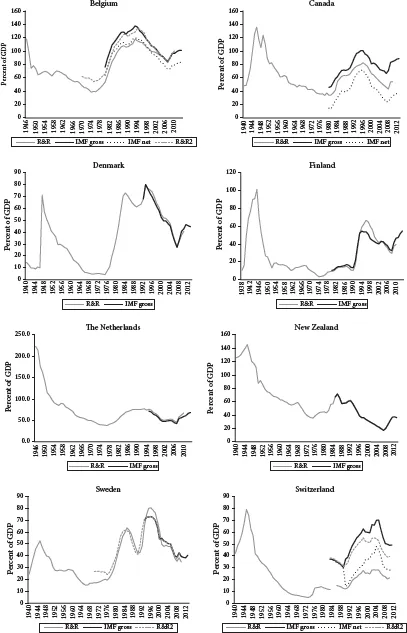

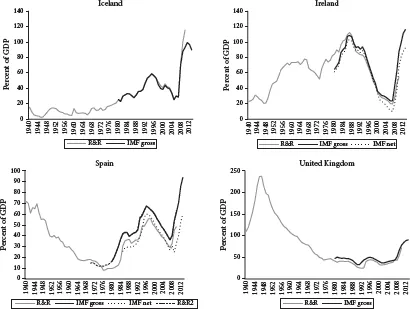

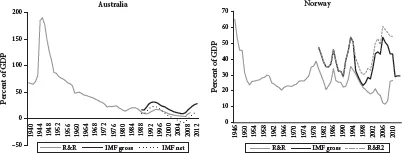

Figure 1.1 illustrates why. The figure shows government debt as percent of GDP (gross domestic product) for 22 OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) countries. It bears emphasizing that when we talk about a rising or falling level of debt we mean debt as a percentage of GDP and not its absolute level. This is, in our view, the most relevant comparison; the ability to pay surely is more closely related to debt in relation to income (GDP) than its absolute level alone, even if expressed in constant value of money. Also, it must be noted that the “debt” we are talking about in this book is government debt and not private debt. Excessive private debt financing creates its own problems,3 but is not a subject of this book.

The countries we are looking at are all “traditional” OECD members from before the end of the cold war and so do not include the countries of Eastern Europe and other relatively recent members such as Chile, South Korea, Israel and Mexico.4 These traditional OECD members comprise most of the richest countries in the world and those that have gone furthest in developing their welfare states, a point not without relevance, as is discussed later (a few rich countries, one of them being Singapore, are not members of the OECD). The series begin at somewhat different times, but for most countries they begin at the end of the Second World War or even a bit earlier. With few exceptions the series show a sharply rising trend from about the mid-1970s. In some countries the debt has now attained a level comparable to what it was at the end of the Second World War. An uninitiated observer might ask by what comparable calamity these countries have been hit in the years since the 1970s.

(a) the relentless borrowers

(b) the repentant borrowers

(c) victims of the financial crisis

(d) the debt avoiders

FIGURE 1.1 Government debt, in percent of GDP

Sources: Reinhart and Rogoff (2011), used with permission, and IMF’s World Economic Outlook database.

The countries for which the debt series take an upward, and in some cases an apparently irreversible turn around 1975, are Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Portugal, Spain, and Switzerland. For some others the debt began to rise a bit earlier or later. Italy and Sweden began to accumulate debt earlier than this; Italy already in the early 1960s and then more rapidly from 1970 on, Sweden from the late 1960s and then more rapidly from the mid-1970s. The United States began to accumulate debt from 1981, the year President Reagan came into office. So did Canada, although presumably without Reagan having anything to do with it. The United Kingdom and Australia are notable exceptions and saw little change in their government debt in the 1970s or 1980s, continuing to wind down their debt from the Second World War.

Some countries have continued to accumulate debt virtually without interruption. This is true of France and, surprisingly perhaps for those who follow the news, also Germany. It is largely true of Japan, the United States, Austria, Greece, Italy and Portugal as well, even if the buildup in Austria and Greece slowed down temporarily, and Italy managed to reverse it for a few years (1995–2003), as did the United States under President Clinton (1994–2001). We could call these eight the relentless borrowers. Yet other countries have managed to reverse the buildup of debt, even if some of those have resumed debt accumulation in the wake of the financial crisis of 2008; Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands (in 2013 almost back at the top reached in 1994), New Zealand, Sweden and Switzerland. Sweden, incidentally, is now among the European Union countries with the lowest debt to GDP ratio and largely avoided any “relapse” into debt accumulation in the wake of the financial crisis. We may note that all of those that have managed to reverse the accumulation of debt are relatively small countries. Perhaps we could call them repentant borrowers.

Then there are a few which experienced rapid buildup of debt in the wake of the financial crisis of 2008, from a moderate level to crisis or near-crisis proportions caused by a collapse or at least precariousness of their banks. These are Iceland, Ireland, Spain and the United Kingdom. Iceland’s and Ireland’s debt went from 25 percent of GDP to over 100 over just a few years, Spain’s from 35 to 85, the United Kingdom’s from 40 to 90. These could be labeled victims of the financial crisis. Finally, there are two countries, Australia and Norway, that are difficult to bundle with any other. In Australia there has been some accumulation of debt since the financial crisis, but to a level still moderate by comparison, about 30 percent of GDP. Norway is, of course, a highly special case because of its petroleum wealth, which has been transformed into a huge financial wealth of the Norwegian government, a process that is still ongoing (the Norwegian petroleum fund is the largest sovereign wealth fund in the world). Like Norway, Australia owes its good fortune in no small measure to its riches of mineral resources.

Why worry?

Observing the formidable buildup of government debt over such a long time in so many countries, and rich ones at that, begs three questions: (1) why has it happened; (2) is it a problem; and (3) if it is, what would be the “safe” or “sustainable” level of debt? We attempt to answer the first question in the following chapters, but first a few words about what the problem might be and what the sustainable level of debt would be. Accumulating debt may work quite smoothly for quite a while in “good” times. Tax revenues will rise in a growing economy even without increasing rates, and even if the debt is growing at a slow but steady rate it may not raise eyebrows among lenders. But if a country falls into a recession, especially a deep and protracted one, eyebrows will be raised. In a recession government revenues fall while expenditures increase; taxes decline while welfare expenditures for the unemployed rise and others remain as committed, and the borrowing requirement of governments increases fast. Then it may dawn on lenders that they might have been overconfident in lending to governments. Hence, at the same time that governments need to cover a hopefully temporary shortfall in their revenues, lenders may suddenly become unwilling to lend more. Governments may then find themselves in a situation similar to going to the pawnbroker; they will be able to sell new bonds (in addition to debt and the “rolling over” of existing debt) only with a huge discount, which in turn will make it still less likely that they will ever pay back their debt. The breakdown of confidence is likely to be sudden, causing panic in policy circles. We have seen a bit of that in recent years. For a time the return on government bonds in Southern Europe (Italy, Greece, Spain and Portugal) rose way above the return on German, French and British bonds. This essentially means that the bonds sold at a discount; the return on the bonds is a predetermined amount, but if the bonds can be sold only at a price lower than their nominal value, the effective return expressed as a percentage of the market price goes up.

But pinpointing a sustainable debt level, that is, debt as a percent of GDP, is easier said than done. Consider Japan and Greece. Japan has the highest government debt level of any country, almost 240 percent of GDP as of 2012, Greece “only” 175 as of 2013. Yet we hear nothing of bondholders losing confidence in the Japanese government to pay back its debt, while the case of Greece is too well known to need much elaboration. So what is the difference? The lenders to the Japanese government are mainly Japanese individuals and firms, and these have not, yet anyway, lost confidence in the Japanese government’s ability to pay them back. Besides, Japan has its own central bank to which it can resort in order to pay its debt, although central bank financing of debt is not without its own risk, as the post–First World War history of Germany, Austria and Hungary shows. Furthermore, the Japanese central bank holds enormous foreign assets in the form of US dollars. Greece borrows largely from foreign lenders and does not have any central bank of its own to fall back on if it becomes impossible to roll the debt forward (redeem old bonds with new ones) and finance an ongoing deficit. So the question of debt sustainability involves questions about who owns the debt and who controls the currency and what assets the government may have. There is no single magic number that fits all countries telling us how much debt a government can take on without running into difficulties.

Or consider Spain versus the United States. Government debt in the Unites States was more than 100 percent of GDP in 2013, while in Spain it was “only” a bit over 90. Yet it was Spain which experienced collapse in bondholders’ confidence and had problems in rolling forward its debt, while the United States could continue doing so at an almost symbolic rate of interest. The world’s bondholders are obviously willing to take on further American debt despite its relatively high level and with no end to its accumulation in sight, because the US dollar is still the world’s reserve currency. Clearly, the size of national economies and their dominance in the world economy has something to do with how much debt a country can take on. This gets us back to the earlier observation that those countries that have been able to reverse their debt accumulation are relatively small. “Had to” may be a better expression than “were able to.” It is not unlikely that the critical debt level at which bondholders in the world’s capital markets lose confidence in a country’s ability to pay is lower for small countries than for large countries. Another reason why small countries meet constraints on borrowing earlier than large countries is that governments of small countries more often borrow foreign currency, as a deficit on the government’s budget often is accompanied by a trade deficit as well. This increases their exposure to international capital markets.

This gets us to the point that there is less difference between government debt and the debt of private individuals than even reputed economists are prone to pronounce. A legacy of Keynesian macroeconomics is that government debt is something entirely different from debts of individuals and private firms. Hence the pronouncements that governments can “stimulate” their economies by raising expenditures without raising taxes, or perhaps lowering taxes as well. Could they do so endlessly? Hardly. As we have seen, governments can lose the confidence of their financiers. Banks lend only to individuals and firms they expect will be able to pay back, and financiers lend only to governments they expect to be able to pay back. It certainly takes more to lose confidence in a government’s ability to pay than it takes to lose confidence in an individual’s or even a corporation’s ability to pay, but it does not mean that a government will enjoy such confidence no matter what. It is unlikely that Keynes intended his prescriptions to mean a license for governments to borrow without limit, and in fact they cannot even if that limit varies from case to case. The governments of the rich countries of the world would have been in a better shape to tackle the financial crisis of 2008 in the “good old Keynesian way” if they had managed their finances in the preceding years more prudently.

But lenders are not the only ones whose confidence is likely to be lost as a result of unsustainable government debt. Modern democracies are best described as a rule by competing elites, as discussed in Chapter 5. Elites are voted into power, or kept in power, by a mostly uninformed electorate that votes for them in the expectation that they will govern well, which mostly means hi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 The Rising Tide of Debt

- 2 Why Has Government Debt Increased?

- 3 The Cost Disease of Public Services

- 4 The Welfare State: Insurance or Redistribution?

- 5 Democracy and Enlightened Authoritarianism

- 6 The European Union: A Viable Colossus?

- 7 How Sweden Got Out of the Debt Trap

- 8 Conclusion

- Appendix: Data Sources

- Literature

- Index