This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Jewish Resistance to 'Romanianization', 1940-44

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Ionescu examines the process of economic Romanianization of Bucharest during the Antonescu regime that targeted the property, jobs, and businesses of local Jews and Roma/Gypsies and their legal resistance strategies to such an unjust policy.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Jewish Resistance to 'Romanianization', 1940-44 by S. Ionescu in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Teología y religión & Teología judía. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Teología y religiónSubtopic

Teología judía1

Introduction: World War II Bucharest and Its Jews

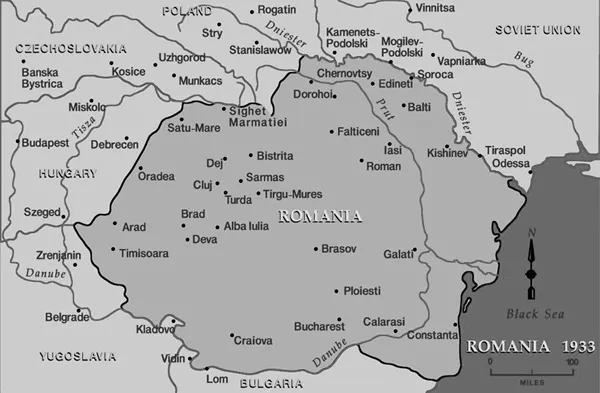

1. Europe 1933, Romania indicated, map – US Holocaust Memorial Museum.

2. Romania, 1933, map – US Holocaust Memorial Museum.

3. Romania, 1942, map – US Holocaust Memorial Museum.

One of the main beneficiaries of the Paris Peace Treaties at the end of World War I and a major French and British ally in Eastern Europe, Romania found itself increasingly isolated two decades later in the context of the growing power of Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, and the new communist state of the Soviet Union. Sensing that the spirit of the era favored nondemocratic regimes and wanting greater personal power, King Carol II transformed the country into a dictatorship in 1938. Fearing Romania’s neighbors, especially the Soviet Union, and hoping to gain German support and marginalize his main domestic competitor, the Iron-Guard fascist party, the dictator made economic concessions and adopted Nazi-influenced policies, including antisemitic legislation.1 Despite these measures, Carol II did not convince Hitler or Mussolini to lend support, and in the summer of 1940, Romania suffered several territorial losses (Bessarabia, Northern Bukovina, Northern Transylvania, and Southern Dobrogea) to the Soviet Union, Hungary, and Bulgaria, who had secured Germany’s approval and cooperation.

This disastrous foreign policy and his complete loss of domestic support led King Carol II to relinquish power in favor of General Ion Antonescu and the Iron Guard (also known as the Legion of the Archangel Michael, hence the name of its members, the Legionnaires). The new rulers came to power in September 1940, transforming Romania into a national-legion state and replacing the royal dictatorship with their own fascist-military regime. Continuing the previous foreign policy of rapprochement with Germany, which guaranteed Romania’s new borders, and hoping to recover its recently lost provinces, Romania joined the Axis in November 1940. Neither Antonescu nor the Iron Guard wanted to share power, however, and they soon engaged in serious disputes over governance methods and supremacy. These tensions broke into several days of urban clashes, known as the January (1941) Rebellion. Backed by the army, Antonescu won and ruled Romania until August 1944 with a government of military and civilian technocrats.2

During World War II, the Antonescu regime did not apply the same policy to all of Romania’s Jewish communities. Antonescu’s obsession with the communist peril was a decisive factor in his hostility toward Romanian Jewry, as he believed that Jews, especially those from Bessarabia and Bukovina, were communist agents.3 Romania’s loss of that territory in summer 1940, under Soviet and German pressure and without resistance, was perceived as a national humiliation and led to the widespread perception of its local Jews as domestic, procommunist traitors.4 Antonescu’s antisemitic policy varied according to the location of Romania’s Jews and their alleged loyalties: mass deportation and death for many of the Jews of Bessarabia and Bukovina and legal persecution, forced labor, and selective deportation for those living in the Old Kingdom, Southern Transylvania, and Banat.5

Antonescu joined the war against the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941 and took Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina back in a campaign that included a widespread massacre of local Jews. After a few months, the Romanian authorities deported most of the remaining Bessarabian and Bukovinian Jews – the city of Czernowitz was a partial exception – to Transnistria, a former Soviet area between the Dnister and Bug rivers. Occupied by Romania for two-and-a-half years, Transnistria became a mass cemetery for Jews who died by execution and of disease, starvation, and exposure. Only a minority of deportees survived. Jews who escaped deportation were subjected to requisitions, forced labor, and other forms of discrimination.

For reasons still debated by scholars but probably prompted by political opportunism, Antonescu changed his radical antisemitic policy in the summer–autumn months of 1942. He suspended deportations to Transnistria, abandoned the plan of sending Romanian Jews to the Belzec death camp, allowed humanitarian aid for deportees, repatriated the orphans, and permitted limited emigration to Palestine. Historians Raul Hilberg and Radu Ioanid have argued that it was not only political opportunism triggered by the Axis’s failure to win the war rapidly that caused Antonescu to change his radical antisemitic policy: another factor was the egos of Romanian officials who resented German interventions in Romania’s domestic (Jewish) affairs, which indicated a breach of sovereignty and the status of Romania diminished to a second-class Axis partner forced to adopt harsher antisemitic measures than Italy or Hungary. The interventions of Romanian democratic politicians, clergy, and the royal family in favor of local Jews also moderated the regime’s anti-Jewish policies.6

When Antonescu and the Iron Guard came to power in September 1940, the regime implemented “Romanianization,” an ideologically driven social-engineering policy designed to build and empower a self-sufficient, productive, and efficient ethnic-Romanian bourgeoisie as a core element of a developed nation state.7 Although proto-Romanianization measures had been adopted by earlier regimes, Romanianization became the government’s central domestic project under Antonescu.8 To create an ideal society based on ethnonationalism, the architects of Romanianization envisioned the exclusion of “foreigners” (ethnic minorities, especially Jews) from the economic sphere through property seizure and exclusion from employment and by returning control over the wealth and economic goods in the country to deserving citizens of “correct” ethnicity.9

The Antonescu regime implemented Romanianization in several stages, each with its own characteristics. Stage one of Romanianization, which developed between September 1940 and January 1941, was characterized by seizure of rural property, appointment of special and Romanianization commissars to Jewish- and foreign-owned companies, physical violence, and plunder of personal property and businesses. Antonescu and the Iron Guard shared power during this period, and many fascists played an important role in legal and, especially, illegal Romanianization. Their involvement in robbery and violence against local Jews and other domestic “enemies” resulted in tensions with the traditional establishment and, ultimately, with Antonescu himself. During this initial stage, the pro-Antonescu bureaucracy complained about the disorganized, anarchic, and violent measures taken by Iron Guard fascists to implement Romanianization, which resulted in substantial financial losses and threatened the state’s economic future.10 As we shall see in Chapter 3, “The Romanianization Bureaucracy,” after the Legion’s defeat in the rebellion of January 1941, most of the fascist party members were excluded from participating in Romanianization.11

Despite the conflict between Antonescu and the fascist rebels, the Romanianization process continued. Authorities did not abandon the policy of excluding Jews from Romanian economy and society but now envisioned this outcome in a more orderly, legal framework.12 The main principles remained the same: seizure of Jewish property and exclusion from employment and businesses. In addition to a new emphasis on respecting the “legality” of the process, the second stage of Romanianization was characterized primarily by confiscation of urban real estate, business restrictions, and exclusion from private employment. Chapter 4, “The Beneficiaries of Romanianization,” discusses how many of the urban properties expropriated by the state were distributed (rented in the first place) to “deserving” ethnic Romanians, such as refugees, civil servants, officers, veterans, and entrepreneurs. The exclusion of Jews from private employment, accompanied by targeted hiring of ethnic Romanian replacements, aimed to create a skilled cadre of dedicated industrial and commercial specialists to strengthen the nation’s labor potential. Dismissing Jewish employees created job openings for ethnic Romanian refugees and unemployed civil servants. The regime thus hoped to lessen unemployment and strengthen the precarious economic situation of ethnic Romanian refugees who flooded the country, and Bucharest in particular, after territorial losses in the summer of 1940.

The regime did not exclude all Jews from the business sector or seize all Jewish companies. The involvement of Romania in World War II, in June 1941, triggered the mobilization of the economy for war production and changed the government’s perspective on Romanianization: the need for a stable and productive war economy trumped rapid Romanianization of labor and capital and provided a strong argument in favor of a moderated and gradual Romanianization. Antonescu’s worries that radical Romanianization would paralyze the economy during the war effort and that the Axis might lose the war or negotiate peace (with unforeseen implications for Romania), as well as his belief in justice and the rule of law, moderated Romania’s antisemitic policy.13 In the context of a Romanian economy dominated by a backward agricultural sector and fragile industry and commerce, it appeared counterproductive to paralyze the society through rapid elimination of many of the available specialists – the Romanian Jews.14 Thus, breaches of the Romanianization of employment and businesses were likely to escape punishment.

Although it did not escape the influence of Axis partners, the Antonescu regime pursued its own brand of economic nationalization. Rooted in local tradition, Romanianization of the economy reeked only superficially of Nazi influence. Although Romania contributed substantially to Axis military efforts, it proved a much more reluctant economic partner and bargained for the concessions it made to German interests. Indeed, the government sought to minimize German involvement.

Antonescu’s Romanianization measures fell into two major categories: negative/destructive initiatives that harmed certain groups and positive/constructive plans to help others. Expropriation decrees, various interdictions, and exclusion from employment were the primary negative measures used to destroy, or at least undermine, minority businessmen and workers. Distributing confiscated assets and jobs to “deserving” citizens, awarding loans to ethnic Romanian entrepreneurs, and appointing Romanianization surveillance bureaucrats at numerous foreign-owned companies were social welfare measures that helped the hegemon population.15

Romanianization in the context of Romanian modern history and previous nationalization policies

Nationalization of real estate belonging to different categories of citizens and foreigners and subsequent distribution to needy and deserving citizens emerged from the very beginning of modern Romania (1859). The Romanian state targeted for expropriation the rural land of undesirable groups, such as religious institutions (1863), Ottoman Muslims (nineteenth century), wealthy boyars (1918–1921), and Hungarian “absentee” landlords (1919–1921).16 Usually, poor peasants were the main beneficiaries of these land reforms since they represented the absolute majority of ethnic Romanians (75.3 percent according to the 1930 census) and lived under difficult circumstances.17 Engaged in state and nation building from the mid-nineteenth century on, local elites considered ethnic Romanian peasants to be the core and the reservoir of the nation, the true keepers of pristine values and customs. Taking the long view, Antonescu’s Romanianization continued the tradition of nineteenth- and twentieth-century expropriations aiming to consolidate the national community and solve its social and economic problems.18

World-War-II Romanianization possessed some specific features, however. While the main beneficiaries of all previous expropriations had been poor peasants, the Antonescu regime sought to empower and develop the ethnic Romanian bourgeoisie in particular by distributing Jewish urban real estate, jobs, and businesses among them. In the Old Kingdom, the distribution of rural land to peasants represented only a secondary goal for Antonescu. Contrary to previous nationalizations, the value of land expropriated by the Antonescu regime (45,035 hectares evaluated at 5,063,364,350 lei) was insignificant compared to the value of urban properties (75,385 apartments evaluated at 59,000,603,573 lei).19 The mass expropriation of urban real estate and businesses was something new for Romanian domestic politics. The main target of Romanianization was the urban, domestic, foreign bourgeoisie, especially Jews, and not domestic or foreign land owners as in the past.

The second major aspect differentiating Romanianization fro...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Maps

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- 1 Introduction: World War II Bucharest and Its Jews

- 2 Romanianization Legislation: Concepts, (Mis)interpretations, and Conflicts

- 3 The Romanianization Bureaucracy

- 4 The Beneficiaries of Romanianization

- 5 Romanianization versus Germanization

- 6 Deportation and Robbery: The Roma Targets of Romanianization

- 7 Jewish Legal Resistance to Romanianization

- 8 Sabotaging the Process of Romanianization

- 9 Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index