![]()

Part I

Fire at the Cape from Prehistory to 1900

![]()

1

Fire at the Cape: From Prehistory to 1795

Fire … is very common in the dry season, when the Hottentots usually set fire to the dry herbage and grass everywhere . … [I]t is very difficult to keep the fire from the ripe grain or to extinguish it.

Journal of Jan van Riebeeck, August 16591

The ground is, indeed, by [burning] stripped quite bare; but merely in order that it may shortly afterwards appear in a much more beautiful dress, being, in this case, decked with many kinds of annual grasses, herbs, and superb lilies.

Anders Sparrman, mid-1770s2

Night comes in; and the city, the road, and the whole neighbourhood, enjoy a spectacle so much the more magnificent, as they are not ignorant of the cause of it [bush fire] … for the extent and height of this conflagration give [Table] mountain a more dreadful appearance than the lava does to Vesuvius.

François le Vaillant, Cape Town, early 1780s3

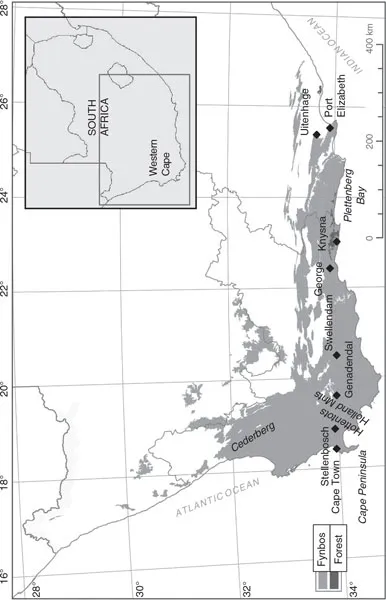

Hominids have inhabited what is now South Africa for around three million years, and humans have occupied the southwestern Cape for nearly half of that time. This region falls within the fynbos biome which occupies the mountains and coastal strip of southern South Africa, within the winter- and ‘all-year-round’ rainfall regions. (A biome is a unit defined by climate, major disturbances like fire and corresponding life-form patterns.) The fynbos biome is actually made up of three main vegetation types: fynbos, renosterveld and strandveld (and – relatively – small patches of forest). Because of its fragmented nature, Takhtajan’s idea of a Cape Floristic Region is often used to enable researchers and managers to think coherently about conserving and managing the region.

The plants of the three major vegetation-types of the Cape Floristic Region are adapted to local fire regimes, meaning patterns of burning. The fire historian Steve Pyne compares fires and fire regimes to storms and climate: within a climatic region, different kinds of storms occur in a seasonal and annual pattern recurring over time. Fire regimes are an amalgam of the following aspects of fires in landscapes over time: fire spread patterns, fire intensity, the size and distribution of fire patches, fire frequency and seasonality. Major shifts in fire regimes (e.g. more frequent, or more intense, fires) can kill these plants (they are not adapted to fire per se). Weather events and climatic variations, or changes in human burning practices (including fire exclusion), can change the structure and species composition of plant communities. For instance, wet winters followed by long, hot summers encourages vegetation growth and then creates ideal conditions for fires to spread – lightning or falling rocks providing natural ignition sources. Frequent fires encouraged by climatic cycles and good fire weather, or human veld (bush) burning, favour grasses over some of the larger shrubs in renosterveld and fynbos.4

The first human explorers of the region were hunter-gatherers, using fire for warmth, cooking and hunting. They encountered numerous antelope – including eland, mountain zebra, quagga (extinct by 1883), red hartebeest and grey rhebuck – as well as large browsers like rhinoceros. The grazing animals and their predators prospered on the more nutritious renosterveld rather than the nutrient-poor fynbos, but within these broad constraints, veld burning would have encouraged grassy species more palatable to grazers. Based on observations of hunter-gatherers in the wider region dating back to the seventeenth century CE, it seems likely that the region’s first human inhabitants burned away old vegetation to attract game to the resulting young herbage. Deacon suggests that fire-stick farming has been practised in the southwestern Cape for at least 100,000 years. Here, hunter-gatherers burned seasonally to find or maintain populations of fire-adapted food plants including carbohydrate-rich geophytes like watsonias and gladioli (which propagate from underground corms or bulbs). Evidence from rock shelters indicates that hunter-gatherers moved seasonally between the coast, which they occupied during the wetter winters, and the mountains with their dependable water sources during spring and summer.

The arrival of Khoikhoi pastoralists around 2000 years ago changed this pattern of life. By 1800 years ago pastoralists and their herds were forcing hunter-gatherers, and probably wild animals, into the more mountainous and marginal environments of the fynbos biome. These hunter-gatherers introduced more frequent burning (than caused by lightning or falling rocks) to the mountainous areas. They may have remained there, with their fires, for most or all of the year. On the plains, the Khoikhoi burned the vegetation seasonally to provide fresh grazing for their sheep and cattle. Sheep were present in significant numbers from around 1600 years ago, with cattle appearing in the archaeological record around 1300 years ago.5

Map 1.1 Western Cape, South Africa, showing fynbos biome and indigenous forests

Source: Base map from M.C. Rutherford, L. Mucina, L.W. Powrie, 2006, ‘Biomes and Bioregions of Southern Africa’ in L. Mucina, M.C. Rutherford (eds), The vegetation of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland, Strelitzia 19 (Pretoria: South African National Biodiversity Institute), pp. 30–51.

Smith has reconstructed the Khoikhoi peoples’ seasonal movements of livestock from one grazing area to another (transhumance patterns) from historical records dating back to the mid-seventeenth century. The Goringhaiqua (called ‘Caepmen’ by seventeenth-century Dutch settlers) and Gorachoqua (called the ‘Tobacco Thieves’ by the Dutch) shared the southern pastures of the Western Cape. They appear to have used the pastures around the Cape Peninsula in early summer, before firing the vegetation and moving east onto the coastal renosterveld towards the Hottentots Holland Mountains, and thence anti-clockwise to return the coast along the course of the Diep River. This seasonal movement allowed the pasture to recover from heavy grazing and prevented the trace-element deficiency and related livestock illnesses that would result from year-round use of nutrient-poor vegetation types.6

Not much is known about the vegetation before the Khoikhoi arrived, but there is little evidence that the 1500 years of Khoikhoi pastoralism before Europeans arrived degraded the environment of the region. This lack of evidence is partly because the Khoikhoi concentrated their grazing and burning on the more nutritious lowland renosterveld, more than 90 per cent of which is now under crops. Signs of land degradation in colonial times were first noted in the late 1720s, and a shift to a shrubbier state in the Renosterveld was commented on by Sparrman in the 1770s, associated with the effects of overgrazing and selective grazing on European settler farms. There were about 50,000 Khoikhoi in the region at the time the Dutch arrived in 1652, owning hundreds of thousands of sheep and cattle. It is possible that their grazing herds and burning of the veld maintained the renosterveld in a grassier rather than a shrubbier state.7

VOC (Dutch East India Company) rule, c.1652–1795

European settlement and environmental impacts

In April 1652, a 35-year-old Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, or VOC) merchant, Jan van Riebeeck, sailed into Table Bay with his young family and a motley assortment of VOC hirelings to set up a refreshment station for the fleets sailing between Amsterdam and Batavia in the Far East. The journey from Europe to Batavia took five-and-a-half to seven months and scurvy was a major problem. Van Riebeeck had been disciplined and dismissed for private trading on a company ship and volunteered to lead the Cape mission in order to redeem his reputation (he was to be stuck at the Cape until 1662).8

The Dutch established a small settlement and fort on the small renosterveld-clad coastal plain between Table Bay and the sheer cliffs of Table Mountain. They found clans of Khoikhoi pastoralists (whom Europeans had named Hottentots, which is probably a rendering of a Khoi greeting) making use of the Cape Peninsula for seasonal grazing, and strandlopers (beach walkers) who lived off gathering and scavenging along the coastline. On expeditions inland and further north, they came across small bands of hunter-gatherers they called bushmen.9

There were tensions over access to grazing on the Peninsula from early 1655. Once the Dutch established their own herd, and in 1657 granted nine soldiers the right to set up as independent farmers (‘free burghers’) on land the peninsular Khoikhoi were accustome 6 to graze their herds on, conflict was inevitable. VOC officials and the free burghers feared the tens of thousands of livestock the Khoikhoi brought would damage their crops and exhaust the Peninsula’s grazing resources. Open conflict broke out in May 1659, but a year later peace had been restored, the Khoikhoi retaining the livestock they had captured, but fatefully acknowledging the VOC’s sovereignty over the lands settled by the free burghers.10

By 1700 many Western Cape Khoikhoi depended on the colony for their livelihoods, working for free burghers or the company in Cape Town and new settlements like Stellenbosch (settled in 1679) and Drakenstein (1687), or on settler farms. As a result of political fragmentation, settler expansion and a series of smallpox epidemics, by 1800 European settlers dominated all the regions of the southwestern Cape suitable for agriculture or pastoral farming. In terms of their original plan to set up a refreshment station at the Cape, the Dutch failed to establish intensive mixed agriculture. Economic conditions, largely determined by the VOC’s low salaries and strict price control, meant that the free burghers at the Cape were driven to reduce their investment of labour and capital to a minimum. They focused on crops that gave a fast return, and many turned to purely livestock farming.11

The impact of Dutch settlement on the indigenous vegetation, and fire regimes, was threefold. First, sedentary livestock farming and regular, uniform veld burning resulted in overgrazing and selective grazing and, it has been argued, a transformation of grassy renosterveld to a shrubland state of this vegetation type. Second, the extermination of large indigenous browsers like black rhino and eland also contributed to a shift to a more shrubby vegetation state. In 1655, Van Riebeeck’s men killed a rhinoceros stuck in a salt pan near Table Bay. A century and a half later, the leopards which had eaten Van Riebeeck’s geese, the lions which had attacked his oxen and the hippos after which Zeekoevlei (‘Hippo Lake’) on the Peninsula was named, were long gone, along with all the other megafauna. By 1700 there was no game within 200km of Cape Town, hunters having wiped out the animals for food or sport. Third, the conversion, particularly of the more fertile renosterveld areas, to cereal crops and vineyards replaced the indigenous vegetation and disrupted natural fire regimes. Both wine and wheat production were well established by 1700.12

Fire policies and management under VOC rule

Dutch officialdom was opposed to veld burning from the outset. In December 1652 their daily journal noted that ‘to-day the Saldanhars set fire to the grass, and as the fire came rather close to our pasture grounds we requested them not to come so near with their fire’. During the conflicts of 1658 and 1659 they feared the Khoikhoi might use fire as a weapon to burn down buildings or set ripe crops alight. In 1659, Van Riebeeck planted a strip of sweet potatoes ‘2 roods wide outside his grain-fields and vineyard’ to

protect the ripe corn from fire, which is very common in the dry season, when the Hottentots usually set fire to the dry herbage and grass everywhere. Without a crop of low growing vegetables or an open belt in between, it is very difficult to keep the fire from the ripe grain or to extinguish it.

In fact there are no records of runaway grass fires started by Khoikhoi seriously damaging the settlement or its fields and pastures, and the first arson fire is recorded in 1715, when Khoikhoi torched the house of one Pieter Rossouw.13

The authorities experienced considerably more problems over burning from their employees, the free burghers and imported slaves. The structures of the settlement were mostly thatched and there were numerous fires in the early years, most caused by smokers and by sparks flying out of chimneys.14 In February 1691 Commander (later Governor) Simon van der Stel instigated a resolution aimed at fire prevention, and in April a fire brigade was established.15 Between 1691 and the end of Dutch colonial control in 1795, there are 14 subsequent resolutions of council pertaining directly to firefighting and the fire brigade.16 This chapter focuses on fires in vegetation rather than structures, though as we shall see, in Cape Town fires frequently crossed the so-called wildland–urban interface. Living in a town of mostly reed-thatched houses bordering on a mountain covered in inflammable vegetation was a constant worry for the VOC authorities. This was exacerbated by the lack of control they felt they exercised over the mountains’ unregulated open spaces.

On the night of 11 March 1736, a group of fugitive slaves set Cape Town on fire with the (alleged) aim of robbing and murdering in the ensuing confusion. When a strong southeasterly wind sprang up, they started a fire at the southeastern corner of the town. Only desperate firefighting managed to confine it to burning five houses to the ground, including the house of Lieutenant Siegfried Allemann, commander of the colony’s military forces. Otto Mentzel (1710–1801), a Prussian who lived at the Cape from 1733 to 1741, described the terrible punishments exacted on the incendiaries. Three of the captured perpetrators managed to cut their own throats before punishment – with a razor tossed into their cell by an accomplice. Five were impaled, four broken on the wheel, four hanged and two women were strangled slowly while a burning bundle of reeds was waved in their faces. The Council also assembled a commando to rid the mountain of vagabonds, ‘be it Europeans or blacks’, who might have willingly or otherwise started such a fire. The commando were authorised to use hand grenades to drive ‘vagabonds’ out of holes and cracks in the mountain. This was the beginning of a long tradition of blaming mountain fires on vagrants, though fighting fire with fire was perhaps never again so brutally implemented.17

Mentzel described a ‘massive fire station’ on the corner of the square between the castle and the town, and was of the opinion that the firefighting ‘organisation is so perfect that many European cities might profitably take a lesson from the Cape’. All slaves, whether privately or Company-owned, were obliged to assist in firefighting. Slaves carried the hoses, worked the pressure engine and fetched water. Soldiers did not assist with firefighting, retreating rather to the castle where they locked the gates and stood by in readiness to cope with any rioting by slaves.18 This provides a vivid picture of the tenuous nature of colonial control as perceived by the Dutch authorities.

Mentzel also provides one of the first descriptions of a major bush fire on Table Mountain. Referring to Peter Kolb’s book about the Cape (of 1719), he confirms that he too saw Kolbe’s ‘carbuncle’ and ‘crowned serpent’ on Table Mountain at night. He explains that these are descriptions of bush fires, which he attributes to the spontaneous combustion of dry bushes by solar rays concentrated on Table Mountain through reflection off Devil’s Peak and Lion’s Head. The burning bushes resemble Kolbe’s ‘carbuncle’, and where a fire spreads upwards from bush to bush, a ‘crowned serpent’ appears. Mentzel writes:

Upon one occasion during my stay at the Cape the whole of Table Mountain was illuminated in this fashion; it happened after several days of torrid heat without a breath of wind, and formed a magnificent spectacle at midnight. A singular feature about these bushes is that though they are of soft wood and appear to be little more than an inch in diameter they burn very slowly. In my opinion they either contain a fire-resisting substance like phlogiston or the slowness of the combustion is accounted for by the ignition taking place at the top, the tips of the branches catch fire, which then pushes its way down the stem to the roots. Each bush usually contains some moisture from the evening dews, and this hampers the spread of the flames. Even if the fire spreads to the roots the bushes spring up anew the following year.19

In 1742, making fires on the beaches at night (usually from old kelp), or in the nearby veld, was prohibited to prevent ships coming to grief in Table Bay through mistaking these fires for the watch fire on Robben Island. Other resolutions of council condemned torch-carrying drunks and smokers and forbade shooting in the streets at night, particularly on New Years’ Night.20

Lessons from the Khoikhoi

From the outset the Dutch had noted the Khoikhoi’s practice of firing the veld before moving on to fresh grazing grounds. In the 1650s, the sight of smoke rising over the flat plains to the north had usually been a welcome one because it meant Khoikhoi were approaching the Peninsula, heralding an opportunity to trade copper and tobacco for livestock. When some free burghers took up livestock farming, letting their cattle and sheep range widely on the veld, they copied Khoikhoi practices including veld burning. Fo...