This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Hart Crane's Queer Modernist Aesthetic

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Hart Crane's Queer Modernist Aesthetic argues that the aspects of experience which modernists sought to interrogate – time, space, and material things – were challenged further by Crane's queer poetics. Reading Crane alongside contemporary queer theory shows how he creates an alternative form of modernism.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Hart Crane's Queer Modernist Aesthetic by N. Munro in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Modern Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

American Decadence and the Creation of a Queer Modernist Aesthetic

Not very many people writing in 1916 would have been so bold as to link the disgraced Oscar Wilde, who had located himself so snugly within English society, to an “American Renaissance.” But in his late summer letter of that year to Joseph Kling, editor of the Pagan magazine, Hart Crane did precisely that.

I am interested in your magazine as a new and distinctive chord in the present American Renaissance of literature and art. Let me praise your September cover; it has some suggestion of the exoticism and richness of Wilde’s poems (qtd. in Unterecker 46).

This letter, which Kling subsequently published in the October issue, links together two of the key ideas that the following two chapters explore: the extent to which Decadent writing affected Crane’s work, and how far and why visual art shaped his queer aesthetic. In this chapter I suggest that, rather than being a youthful dalliance, as many critics have assumed, Decadence was a crucial influence upon not just Crane’s early work, but upon poetry that might be considered typically modernist. By examining the juvenilia seriously, a number of important concerns can be discerned that reappear later in Crane’s career, such as an affirmation of Otherness and the place of the queer subject in the world.

Although it is clear from the letter to Kling that Crane appreciated Wilde’s example, it is also true, I suggest, that he was critical of Wilde’s submission to normative authority, and he offered a critique of Wilde’s actions in his poem “C33” (1916/1916). At this point in his writing career, critics generally assume that Crane shook off the languor of Decadence, but it continued to be a prominent shaper of Crane’s style and content, and he sought to blend together the kind of masculine language that he was absorbing from Ezra Pound and Imagism with a style of Impressionism drawn from Wilde’s poetry. In addition, Crane developed a number of unfashionable links with a sexually ambiguous Hellenism through his extensive reading of Walter Pater, and his poem “For the Marriage of Faustus and Helen,” seen, together with The Bridge, as a rejoinder to Eliot’s The Waste Land, which contains a significant number of Paterian moments. The positive response to the poem proved to Crane that he could write an alternative modernism and be accepted.

(American) Decadence

As Cassandra Laity observed in a special issue of Modernism/modernity (427–30), Charles Baudelaire was identified as the crucial figure of Decadence by T. S. Eliot and Walter Benjamin. This emphasis, Laity explains, together with the association of Baudelaire with perceptions of the urban environment and its inhabitants, particularly the flâneur and flâneuse, has meant that other forms and expressions of Decadence have been neglected. Laity argues that “British Decadence and/or Aestheticism is still understood by many modernists as a ‘Baudelairian’ derivative or dismissed as blandly ‘effeminate,’ socially irrelevant, and elitist” (427). Since he was influenced by British decadents such as Oscar Wilde and Lionel Johnson, criticism of Crane’s juvenilia has generally followed much the same path, only more so, since Crane’s sexuality is considered to be another reason for his attraction to writers perceived at the time to be perverted.1 Critics such as Thomas E. Yingling, Langdon Hammer, and more recently and in more detail, Brian M. Reed, have granted greater significance to Crane’s ties with Decadence, but each provide reasons for Crane’s later dismissal of these links. What these critics neglect, and what I want to draw attention to here, are the elements of Decadent thought that continue to appear in Crane’s work throughout the 1920s.

Crane discovered many of the little magazines to which he was later to submit work, including the Pagan, Bruno’s Weekly, and the Little Review, in Richard Laukhuff’s bookstore in Cleveland which, until Crane moved to New York and sought out the publishers of these periodicals in Greenwich Village, proved an invaluable source of the latest work of authors from America and Europe. Many of the issues of these publications from the 1910s featured Decadent European authors.2 It was from Europe that the definitions of decadence originally came: first in the 1830s through an ongoing debate in French literature and criticism featuring Désiré Nisard, Théophile Gautier, and Paul Bourget, and then in the work of Arthur Symons. Initially, Symons’s work appeared in England, but in 1893 he contributed an article entitled “The Decadent Movement in Literature” to Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in New York. In this he explained that “both Impressionism and Symbolism convey some notion of that new kind of literature which is perhaps more broadly characterized by the word Decadence” (866). Symons claimed that this movement “has all the qualities that mark the end of great periods, the qualities that we find in the Greek, the Latin, decadence: an intense self-consciousness, a restless curiosity in research, an over-subtilizing refinement upon refinement, a spiritual and moral perversity […] this representative literature of to-day, interesting, beautiful as it is, is really a new and beautiful and interesting disease” (858). Such a description reflects the over-wrought, over-sophisticated, paradoxical state of modern society as many critics saw it, particularly in the cities, but it also suggests Symons’s ambiguous attitude to this “new and beautiful and interesting disease.” Its “representative” nature and place at “the end of [a] great period” suggests a literature that – whether critics appreciate it or not – is worth their study. If anything he admires certain of its beauties and what he referred to as its “classic qualities” (859). However, by the time he published The Symbolist Movement in Literature in 1899, Symons had changed his opinion. Whilst essentially discussing the same authors, he re-branded the movement “Symbolism” and disowned “Decadence.” He claimed now that Decadence was no more than an “interlude, half a mock-interlude,” which “diverted the attention of the critics while something more serious was in preparation” (4). That “something” was the Symbolist Movement, and Symons proves keen to distinguish Symbolism from Decadence, asserting that Decadence can only be used “when applied to style; to that ingenious deformation of the language, in Mallarmé, for instance” (4).3 He also observes that “[n]o doubt perversity of form and perversity of matter are often found together, and, among the lesser men especially, experiment was carried far, not only in the direction of style” (4, emphasis added). In suggesting that “perversity” went beyond the page, Symons also hints at the need to distance himself from notions of Decadence, for since 1895 the label had been associated with Oscar Wilde, who had been tried and convicted in that year for “acts of gross indecency with other male persons.”4 In the four years between Symons’s article on “Decadence” and the publication of his book on “Symbolism,” the subsequent public and literary exclamations against Wilde and everything for which he was assumed to have stood, make it clear that we can read “experiment […] not only in the direction of style” as an attack on those, like Wilde, who carried on queer relations, and that style and sexuality were thus intimately connected.5 Such attacks were sustained both in Britain and beyond: Neil Miller relates how “in America, some 900 sermons were said to have been preached against Wilde from 1895 to 1900” (48).

So, as David Weir has noted, a rise in decadent culture in the 1910s might have seemed “incompatible with the Puritan, progressive, capitalist values of America,” but this might indeed have been what attracted Crane to Decadent work in the first place (Decadent Culture 1). It was a reaction against the business culture of his father (Crane would later concur with Waldo Frank’s analysis that “American Industrialism is the new Puritanism, the true Puritanism of our day” (Frank, Our America 98)), and the limited horizons of an Ohio situation that he always disparaged (“in this town, poetry’s a/Bedroom occupation,” he wrote in “Porphyro in Akron” (1920–1921/1921)) (CP 152). Decadence was an extreme alternative, an Otherness. In The Mauve Decade: American Life at the End of the Nineteenth Century, published in 1926, Thomas Beer dates the Decadent revival in American culture to 1916, just as Crane was discovering the little magazines (148). Yet Crane would also have had a general sense of a “decay” within American literature: the Little Review’s September number from 1916 contained twelve blank pages, the issue acting as “a Want Ad” for good work. If Crane took this as an indication of a lack of good American literature, he would have felt quite justified in looking abroad to Europe and England for inspiration. In doing so, Crane absorbed the content, style, and form of writers like Oscar Wilde, Lionel Johnson, and Arthur Symons, and faithfully reproduced it in his juvenilia.

Crane’s Decadence: The outsider and aesthetics

So faithful were Crane’s poems to these writers, that reading them can be like compiling an inventory of typical Decadent features. Matei Calinescu provides a concise summary of such features when he suggests that Decadent art was concerned with “such notions as decline, twilight, autumn, senescence, and exhaustion, and, in its more advanced stages, organic decay and putrescence – along with their automatic antonyms: rise, dawn, spring, youth, germination” (155–56). This kind of imagery is easily located in Crane’s early work from 1916–1917: the poem “October-November” (1916/1916) begins with an “Indian-summer-sun” (CP 136), “Fear” (1917/1917) describes how “on the window licks the night” (CP 138), and “Annunications” (1917/1917) opens by telling of “[t]he anxious milk-blood in the veins of the earth,/That strives long and quiet to sever the girth/Of greenery,” and closes with the sounds of “things […] all heard before dawn” (CP 139). Examining two of Crane’s earliest poems in detail gives a sense of the kind of decadent influences he was absorbing during this period, and also suggests ways in which that work shows the beginnings of his fascination with modes of perception.

The opening stanza of the early unpublished poem “The Moth That God Made Blind” (c.1915–1917/unpublished), illustrates the kind of exoticism that was prevalent amongst decadent writings in the 1890s and in the revival of the 1910s, with its references to “cocoa-nut palms,” “Arabian moons,” and “mosaic date-vases” (CP 167).6 The poem describes how one moth, who is born with his eyes covered with a “honey-thick glaze,” is led to explore the power of his exceptional wings. The moth flies so high and close to the sun that the glaze on his eyes is burned off, and he can see “what his whole race had shunned” (CP 168): the extent and beauty of the world below. In that same moment, though, he is blinded and his wings “atom-withered,” (CP 169) and he falls back down into the desert.

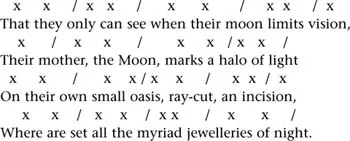

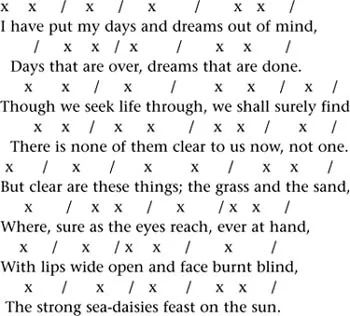

Integrating decadent concerns, the poem often describes the beauty of the natural world as if it were artifice (“mosaic date-vases”), and it does so in the well-structured form of decadent poetry. Crane’s poem is made up of thirteen quatrains, regularly rhymed with a few variations to emphasize key and dramatic moments of the story. Crane also seeks to use a complicated meter, combining a mixture of mostly anapaests and iambs in a way that suggests to R.W.B. Lewis “Swinburnian trappings” (18):

Lewis’s comparison is apt, both in terms of Crane’s use of such a complex meter (it is unlikely that he would have chosen it if he had not had Swinburne as a model), and in terms of the poem’s content, which in its depiction of bitter loss and deep introspection recalls Swinburne’s “The Triumph of Time”:

The diction used and the sentiments expressed in the second half of this stanza suggest that Crane had this poem in mind when he wrote “The Moth That God Made Blind,” since – as shown in the stanza below – it shares images of “sand,” the “hand,” blindness, and the sun, and an attempt to hopelessly seek solace in the knowledge that has been gained from experience.7 The fourth line in Swinburne’s stanza offers a model for the way in which Crane sought to match style to content: the stunting of the line’s anapaests with an iamb to reflect the disillusionment at failed dreams and the understanding of them, is similar to the technique Crane uses in the first and third lines of the stanza quoted above. The addition of an unstressed syllable there to break up the anapaest pattern serves to match the limited nature of the vision described and then suggest the limited space of the moths’ existence on the “small oasis.” In attempting his own versions of such intricacies of form, Crane showed that he had paid extremely close attention to the structures of late Victorian poetry. Brian Reed has argued that Crane’s fascination with Swinburne was still evident as late as 1929, citing a letter that mentioned the English poet’s work, and he shows similarities between Swinburne’s style and Crane’s later work in The Bridge. However, he also claims that even though Crane “never cite[d] Swinburne by name as a source or model for The Bridge [...] his reticence on this point proves little. Pilloried during his first New York period for his fin de siècle leanings, Crane thereafter had reason to be circumspect” (33). If Crane was “pilloried” during his first New York trip, he continued to meet with people like Joseph Kling, who made Crane an associate editor of the Pagan in 1918, and Crane continued to publish work there until 1919. Furthermore, the poem he published in the Little Review in 1918, “In Shadow” (1917/1917), contained many similar traits of style and content to those of his earlier pieces. Yet Crane’s interest in Victorian poetry and Decadence was certainly not restricted to Swinburne. In fact, the works of Decadent writers such as Wilde, Johnson, and Symons were much more significant for him.8

In “The Moth That God Made Blind,” Crane presents an image of the outsider who, like Icarus, is also an over-reacher – a description that would have fitted Oscar Wilde, whose use of paradoxes Crane keenly observed and later criticized in “Joyce and Ethics,” saying that “after [Wilde’s] bundle of paradoxes has been sorted and conned, – very little evidence of intellect remains” (CPSL 199). This technique, however, is critical to the meaning of the poem. The moths can only see “when their moon limits vision,” and at the very moment of revelation, when the moth gains his sight and understands the great potential of the world, he loses both his sight and his life. The very nature of the paradox as a form suggests a struggle, and a struggle against logical – or normative – behavior. In this sense the poem is allegorical, urging that such a struggle is undertaken against the mainstream or dominant. That mes...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations and Notes on Sources

- Introduction: Relationality

- 1 American Decadence and the Creation of a Queer Modernist Aesthetic

- 2 Abstraction and Intersubjectivity in White Buildings

- 3 Spatiality, Movement, and the Logic of Metaphor

- 4 Temporality, Futurity, and the Body

- 5 Empiricism, Mysticism, and a Queer Form of Knowledge

- 6 Queer Technology, Failure, and a Return to the Hand

- Conclusion: Towards a Queer Community

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index