This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Industrial Clusters, Migrant Workers, and Labour Markets in India

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book analyzes three points: employment conditions for migrant workers, the impact of industrialization as part of industrial clusters upon surrounding and outlying villages, and the labour market in industrial clusters. This book examines the cases of two newly developed industrial clusters: Ludhiana in Punjab and Tiruppur in Tamil Nadu.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Industrial Clusters, Migrant Workers, and Labour Markets in India by S. Uchikawa in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Labour Economics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: Development of Industrial Clusters and the Labour Force

Shuji Uchikawa

1.1 Introduction

As an industrial cluster develops, demand for a labour force in the cluster may increase. There are two sources of labour forces in developing countries. First, surplus labour from surrounding villages joins the manufacturing sector. If employment in agriculture is unstable and offers low income, the manufacturing sector may provide better employment opportunities for surplus labour. Therefore, the labour force may shift from agriculture to industry. Many factories outsource labour-intensive processes to households in surrounding villages, a practice that may improve household incomes. Second, the expansion of labour demand in an industrial cluster induces inflows of migrant workers from remote villages. They move to an industrial cluster for employment opportunities and the ability to send remittances to their families back in their home villages. Migrants compare incomes in their home villages with expected incomes from factories in industrial clusters. As the labour force in industrial clusters depends on migrant workers, their inflow affects the cluster’s labour market. If wage and employment conditions are not attractive, the labour force does not shift from agriculture to industry.

This book analyses three points: employment conditions for migrant workers, the impact of industrialization as part of industrial clusters upon surrounding and outlying villages, and the labour market in industrial clusters. This book examines the cases of two newly developed industrial clusters: Ludhiana in Punjab and Tiruppur in Tamil Nadu. Both have grown rapidly since the 1990s as clusters of the apparel industry and depend on migrant workers as their labour force. Surveys were conducted to collect individual and/or household information, which is not available from official statistics. The background of current industrial workers is crucial for the survey as it is theorized that landless and marginal and small farmers are more likely to become industrial workers. Because they lack good educational background and skills, they have difficulty finding high-income non-farm employment.

If their incomes improve after joining the manufacturing sector, income distributions might reflect this shift. Chapters 2 and 3 analyse the survey results. Chapters 4, 5, and 6 examine the results of the survey conducted in surrounding villages. Chapters 7 and 8 investigate labour markets in the industrial clusters.

The shift in the labour force from agriculture to the manufacturing sector has not been smooth in India. Although the manufacturing sector has seen an increase in employment, the share of the manufacturing sector in total employment has not changed. Rural areas have enduring unemployment and underemployment problems. A mismatch between supply and demand in the labour force in industrial clusters seems evident. This book uses the two case studies mentioned above to look for the reasons that prevent labour force in rural areas from joining the manufacturing sector.

1.2 Underemployment in rural areas

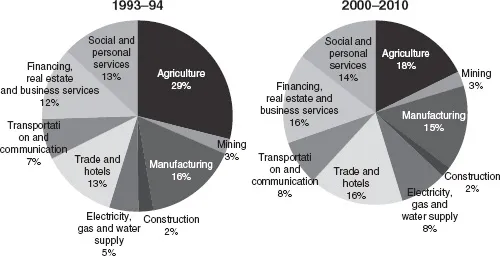

Some industrial clusters face labour shortages. However, this is not a common phenomenon in India. Stable economic growth over the past two decades could not solve persistent unemployment and underemployment problems. The average gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate from 1993–94 to 2009–10 was 6.6 per cent. The structure of GDP changed dramatically during the period. While the GDP share of tertiary industry rose from 50.2 per cent to 63 per cent during the period, agriculture’s share declined sharply from 28.9 per cent to 17.7 per cent (Figure 1.1). Service industries such as transport and communications, as well as finance and business services, contributed to the rapid economic growth. These industries have maintained average growth rates higher than 8 per cent since 1991. However, the GDP share of manufacturing has not changed.

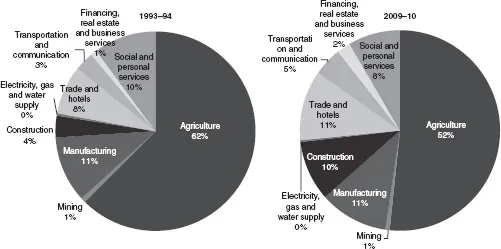

Changes in employment composition do not correspond to those in GDP. National Sample Survey (NSS) provides estimates of employment and unemployment using three different approaches.1 To examine structural changes of employment, usual principal status is selected. While the share of workers engaged in agriculture declined from 62.5 per cent to 51.7 per cent between 1993–94 and 2009–10, the share in tertiary industry rose by only 4.3 percentage points (Figure 1.2). In addition, the share employed in manufacturing did not show significant change. Although agriculture’s share in GDP was only 17.7 per cent in 2009–10, in terms of employment, its share is more than 50 per cent. Existence of surplus labour in rural areas is reflected in the composition of employment. Binswanger-Mkhize (2013) points out that although rural non-farm employment grew between 1999 and 2007, these opportunities primarily went to young males with some education.

Figure 1.1 Composition of GDP (current prices)

Source: CSO, National Account Statistics, Back Series 2007, http://mospi.nic.in/Mospi_New/upload/back_srs_nas.htm, p. 27. CSO, National Account Statistics, 2012, http://mospi.nic.in/Mospi_New/upload/NAS12.htm, p. 12.

Figure 1.2 Composition of employment (according to usual principal status)

Source: NSSO (1997), Table 34 and NSSO (2011), Table 29.

India’s population grew from 846 million in 1991 to 1,210 million in 2011. Naturally, the estimated number of workers2 according to usual principal status increased from 292 million in 1993–94 to 372 million in 2009–10. Worker population ratios (WPR) according to usual principal status slightly decreased from 37.5 per cent to 36.5 per cent during this period (NSSO 2011). This suggests employment growth is not sufficient to absorb the surplus labour force.

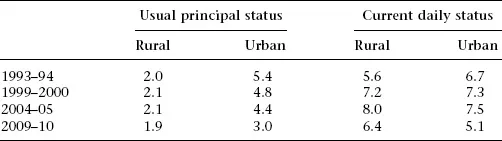

Table 1.1 shows unemployment ratios of males in rural and urban areas from 1993–94 to 2009–10. Two distinct features emerge. First, unemployment rates according to current daily status were higher than those according to usual principal status because current daily status accurately captures underemployment as unemployment. Second, unemployment rates clearly reduced in both urban and rural areas after 2004–05 according to both usual principal status and current daily status.

Rangarajan et al. (2011) and Kannan and Raveendran (2012) estimate employment levels and the labour force in 2004–05 and 2009–10, using the NSS data. Both found that while male employment increased, female employment decreased during the period. Women withdrew from the rural labour force. Rangarajan et al. ascribe this withdrawal from the labour force to additional enrolment in education and the requirements of domestic duties under the guise of income improvement. However, Kannan and Raveendran point out that 72 per cent of women who dropped out of the labour force were 25 years old or older. They suggest that as men lost their self-employment activities, a great number of women also lost their status as unpaid family labour to assist these men. Hirway (2012) argues that women who drop out of the labour force move to low-productivity informal work and/or subsistence work. Himanshu et al. (2011) ascribe the noticeable acceleration of non-farm employment between 1999–2000 and 2004–05 to high levels of entry into this sector by women, children, and the elderly because of acute distress in the agriculture sector. They see the slower non-farm employment growth between 2004 and 2007 as mainly a return to the more usual labour force participation rates, especially for women. The decline of unemployment shows a mixed picture. Although the Indian economy still has unemployment and underemployment problems, employers in Ludhiana and Tiruppur indicate labour shortages.

Table 1.1 Unemployment rates of male according to usual principal status and current daily status (%)

Source: NSSO (2011), p. 155.

1.3 Cluster development, migration, and the labour market

This section reviews literature on migration in India, labour markets in the organized manufacturing sector, the informalization of labour markets in the manufacturing sector, and the impact of industrialization on villages surrounding Ludhiana and Tiruppur.

1.3.1 Migration in India

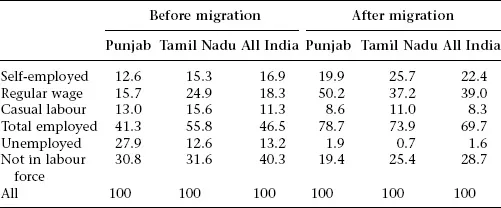

As an economy develops, mobility of the labour force increases. Migration from rural areas to industrial clusters is important to examine how mismatches occur between labour force supply and demand. People migrate for various reasons. The 64th round of the NSS conducted in 2007–08 (NSSO 2010) enquired into these reasons from households that had migrated during the last 365 days. Around 60.8 per cent of responses mentioned employment as the main reason, and 23.8 per cent cited studying as their reason. Table 1.2 shows these two phenomena. First, persons not in the labour force obtained employment after migration. Second, regular wage employees accounted for the highest share of usual principal activity status after migration. In the NSS, regular wage employees include not only persons receiving time wages but also persons receiving piece wages or salaries as well as paid apprentices, both full time and part time. However, regular wage employees do not always have a stable job.

The relationship between poverty and migration has been highly debated. Keshri and Bhagat (2012) analyse the relationship between poverty and short-term migration, utilizing unit level data from the 64th round of the NSS.3 Monthly per capita consumer expenditure (MPCE) is used as a poverty measurement. They classify the number of short-term migrant per 1,000 persons according to MPCE quintiles. The migration rates (the share of migrants in a particular category in populations in that category) in the lowest and second lowest MPCE quintile in rural areas were 44.8 per cent and 32.1 per cent, respectively. The migration rate decreases with increases in MPCE quintiles. Binary logistic models are fitted to assess the effects of socio-economic characteristics on a person’s likelihood of being a seasonal migrant. They find a statistically significant negative relationship between short-term migration in rural areas and household income, land possession, and educational attainment. They conclude that “temporary mobility is higher among the poorer sections of Indian society irrespective of the level of economic development of the states concerned” (p. 87).

Table 1.2 Usual principal activity status of urban male before and after migration (%)

Source: NSSO (2010), p. 84.

On the other hand, Kundu and Sarangi (2007) reveal that the bottom 40 per cent of the urban population accounted for only 29 per cent of total short-term migrants, using data from the 55th round of the NSS. Not only were the rural poor struggling for survival but also better-off households were short-term migrants. They estimate the impact of factors including the level of education, migration status, occupation, nature of employment, and city size on the probability of a person falling below the poverty line. Effective and negative coefficients were found between long-term rural to urban migration and the probability of living in poverty. They deny the hypothesis that urban poverty is a spillover of rural poverty because rural migrants into urban area have a lower probability of being poor than the local population. It is estimated that the relatively better-off rural residents can migrate to urban centres because moving to cities requires initial self-supporting capacity and a certain skill level. They concluded that migration emerges as a clear instrument for the adult population to improve their economic well-being and escape poverty. Because an effective correlation was not found between short-term migration and the probability of living in poverty, they suggest that short-term migration is not restricted to the rural poor struggling for survival but is common among better-off households.

Deshingkar et al. (2006) conducted surveys in six districts in Bihar and found that although the poorest of the poor cannot migrate, schedule castes and other backward castes with low education as well as landless or nearly landless are engaged in both short- and long-distance migration, but usually in the lowest paid jobs. Migration has many costs and risks associated with it. A lack of proper housing and sanitation as well as a lack of sustained access to food through public distribution systems are among the most acute problems that migrants face. In addition, women and children who are left behind suffer from loneliness. Agricultural labouring work, casual labouring work in construction, work in brick kilns, and rickshaw pulling are the four most important categories of work for these migrants. As their remittances improved their households’ incomes, practices such as borrowing foodgrains from the rich to tide over the lean season and borrowing at very high interest rates for survival have virtually disappeared in several places in Bihar. Deshingkar et al. point out that roughly 5–10 per cent of migrating households have been able to accumulate assets as a result of migration. These migrants are in more remunerative work, especially factory work. Deshingkar et al. found that 1500 individuals migrated from Hariharpur village (original population: 4000) to a particular location of Ludhiana, following a migration stream that has existed for the last 10–12 years. Around 70 per cent of migrants are unskilled and will take up any available manual wage work. In the village, 80 per cent of the backward caste, schedule caste, and Muslim families have between one and four migrants from the ages of 17–45 years. These trends can be summarized as follows: “in general, poor and marginal farmers migrated seasonably or commuted and the rich migrated permanently” (p. 11).

Four points can be extracted from the above arguments. First, the short-term migration rate is high in low-income groups. Short-term migration is an instrument of escaping poverty. A factor that should not be underestimated is how migration may reduce dependence on moneylenders. Second, factory work is a relatively remunerative job for migrants from Bihar. Some of them can invest their wages in farming, share cropping and leasing land, or a small business. Third, not only the poor but also better-off households engage in short-term migration to improve their incomes. Fourth, long-term rural to urban migration requires initial self-supporting capacity and a certain skill level.

This book investigates workers’ ties with their home villages. An important point to consider is whether workers in industrial clusters engage in agriculture when they return to their home villages. Employment in the manufacturing sector may be an alternative to farm employment. Kumar (1988) argues that apparel factories employ semi-industrial workers who travel to the cities during the slack agricultural period and return to their villages for sowing, harvesting, and festival seasons. The AEPC report (2009) points out “in the event of good monsoon, the cluster faces labour shortage as villagers opt for cultivation” (p. 200). The seasonality of apparel manufacturing means the industry requires semi-industrial workers able to adapt to the production season.

1.3.2 ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Contributors

- 1 Introduction: Development of Industrial Clusters and the Labour Force

- 2 Migrant Workers in Ludhiana

- 3 Knitted Together: The Life of Migrants in Tiruppur Garment Cluster

- 4 Pattern of Rural Livelihoods in Punjab: The Role of Industrial and Urban Linkages

- 5 Impact of Non-Farm Employment on Landholding Structures in Punjab: Comparison of Three Villages

- 6 Industrial Growth and Indian Agriculture: Insights from Two Villages Near Tiruppur, Tamil Nadu

- 7 Tiruppur’s Labour Market on the Move: An Examination of Its Industrial Relations with Special Focus on the Institutional Actors in the Apparel Industry

- 8 Structure of the Steel Industry and Firm Level Labour Management in Mandi Gobindgarh and Ludhiana

- Index