eBook - ePub

Development Macroeconomics in Latin America and Mexico

Essays on Monetary, Exchange Rate, and Fiscal Policies

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Development Macroeconomics in Latin America and Mexico

Essays on Monetary, Exchange Rate, and Fiscal Policies

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Development Macroeconomics in Latin America and Mexico brings the attention of academics, practitioners, and policy makers to the neglected macroeconomic factors that can account for both the unsatisfactory average growth performance of Latin American and the diversity around this average.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Development Macroeconomics in Latin America and Mexico by J. Ros in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Institutional and Policy Convergence with Growth Divergence in Latin America*

This chapter compares the cross-country growth performance of Latin American countries during the postwar period of state-led industrialization and the economic liberalization period of the last three decades. The chapter describes the major overhaul in economic policies and institutions that Latin America experienced after the debt crisis of the 1980s. At the same time, we look at the growth performance over those two periods. When we compare the rankings in the growth tables for the periods 1950–1980 and 1990–2008, a “reversal of fortune” is apparent: countries, such as Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, that were in the bottom half in the growth table in the period 1950–1980, call them the “losers from ISI”, tend to be in the upper half of the growth table in 1990–2008. And vice versa, countries such as Brazil, Mexico, Ecuador, Guatemala, the “winners from ISI”, tend to be in the bottom half of the table for the same period. The chapter addresses the question of why this reversal of fortune has occurred despite (or perhaps because) the large degree of institutional and policy convergence across the region.

Economic and Political Reforms since the Debt Crisis: Institutional and Policy Convergence

In the first decades of the postwar period, Latin America embraced a paradigm that placed the developmental state at the center of the strategy, with industrialization, which was regarded at the time as critical to increase living standards, as the major objective. Over the past 30 years Latin America has experienced a major overhaul in economic policies and institutions as well as in political institutions. As a result, a “great transformation” has taken place, if we may appropriate Karl Polanyi’s expression for events of a different scale.

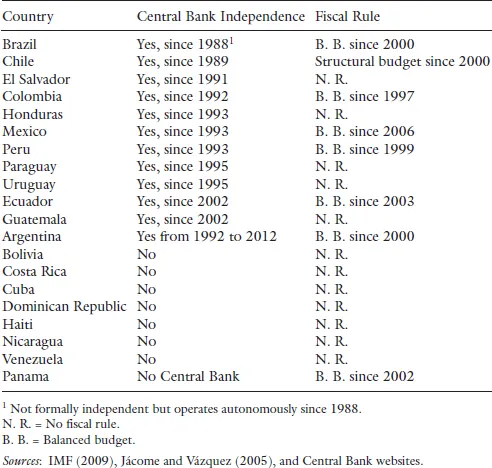

The major policy changes included far-reaching programs of economic reforms in different areas. These changes gave a larger role to the private sector in the allocation of resources and greater scope to market forces and international competition, all this with the goal of entering a phase of strong export-led economic expansion. It is worth recalling what has happened. During and after the adjustment process to the debt crisis of 1982, monetary and fiscal policies were radically transformed. In 1980, in a group of 20 Latin American countries,1 none had an independent central bank. By 2012, a majority of countries (11) had an independent central bank. In addition, in the largest countries (Brazil, Mexico, Chile, Colombia, and Peru) the central bank operated under an inflation-targeting regime with a floating exchange rate and price stability as its sole mandate.2 Fiscal policy went through a similar overhaul. In 1980 no country had a balanced budget rule. By 2012, eight countries had a balanced budget law, generally a strict commitment to balance the budget every year with the exception of Chile, which had a structural budget rule that allowed for fiscal deficits during recessions provided that these were compensated by budget surpluses in boom periods (see Table 1.1).

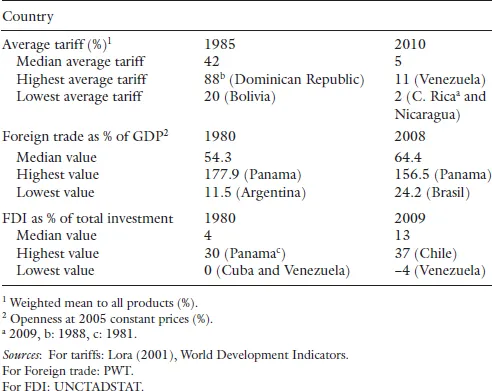

Regarding structural reforms in other areas, the early and prominent components of the reform agenda were trade liberalization and deeper integration into the world economy based on comparative advantages, as well as a broad opening to foreign direct investment (FDI). As shown in Table 1.2, tariffs were sharply reduced and the tariff structure radically simplified as nontariff barriers were largely eliminated. The median average tariff which in 1985 was 42% fell to 5% in 2010 and the highest average tariff went down from 88% to 11%. These changes were so far-reaching that, as argued in Ocampo and Ros (2011), the objective of setting low tariffs was achieved to a much greater extent than in the classical period of primary export-led growth in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Table 1.1 Central Bank Independence and Fiscal Rules (2012)

Table 1.2 Openness to International Trade and Foreign Investment

A wave of free trade agreements (FTAs) or custom unions took place with North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which came into effect in 1994), in the North and MERCOSUR (1991) in the South being the most important initiatives. Moreover, under the leadership of Mexico and Chile, a wave of bilateral or multilateral FTAs was launched. All this contributed to a sharp increase in the weight of international trade in the economy. As shown in Table 1.2, the share of exports and imports in gross domestic product (GDP) increased for the median country from 54.3% to 64.4%. Some spectacular increases were recorded by Argentina (from 11.5% to 45.1%), Mexico (from 28.4% to 58.8%), Costa Rica (from 56.9% to 100.8%), and Paraguay (from 47.4% to 105.9%) (see Table 1.A.1 in Appendix). In turn, the relaxation of FDI regulations led to a sharp increase in the share of FDI in gross capital formation. The median country increased this share from 4% to 13% (see Table 1.2) and for some countries this share rose to over 30% (see Table 1.A.2 in Appendix).

Trade and FDI liberalization were accompanied, in addition, by the elimination of exchange controls and domestic financial liberalization. The latter included the liberalization of interest rates, the elimination of most forms of directed credit, and the reduction and simplification of reserve requirements on bank deposits. Although it was also accepted that financial liberalization required regulation to avoid the accumulation of excessive risks in the financial system, the full acceptance of the need for regulation only came after a fair number of domestic financial crises (in particular the Tequila crisis of 1994–1995).

Another component in the agenda of structural reforms was the privatization of a large set of public enterprises together with the opening to private investment of public services and utilities sectors. The more general deregulation of private economic activities was also part of the agenda. The privatization process was more gradual than in the case of trade liberalization and a number of countries kept public sector banks and a number of other firms, notably in oil and infrastructure services (water and sewage more than electricity and telecommunications).

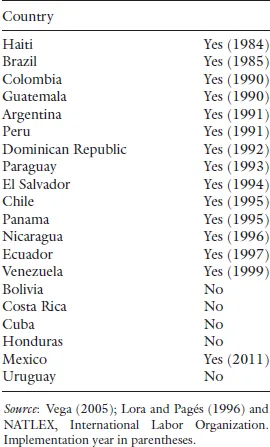

There was, finally, an agenda of at least partial liberalization of labor markets, but here political factors limited the scope of the reform proposals (Murillo et al., 2011). Even then, as many as 13 countries in our group of 20 undertook changes in labor market regulations with the aim of making the labor market more flexible (see Table 1.3).

Table 1.3 Labor Market Reforms

Changes in political regimes went hand in hand with economic liberalization. Following Przeworski (2004) criteria to classify a political regime as authoritarian or democratic, Table 1.A.3 in the Appendix shows that in 1980 there were only four countries (Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, and Venezuela) with democratic political regimes so that 85.1% of the population of the 20 Latin American countries lived under authoritarian regimes. In 2009, only one country (Cuba) continued to be authoritarian, representing 2% of the total population.

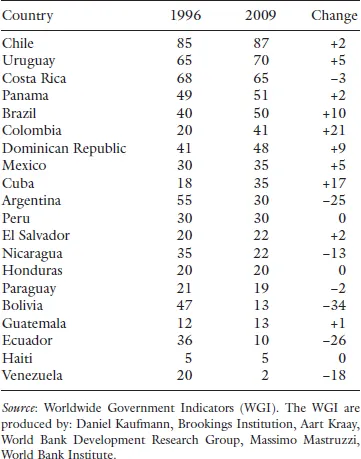

Moreover, perceptions about the rule of law in Latin America, available for 1996 to 2010 from Worldwide Government Indicators (WGI), show a steady improvement since 1996. The percentile rank of Latin American countries improved from 1996 to 2009 (see Table 1.4), with only six exceptions (Argentina, Bolivia, Ecuador, Nicaragua, Paraguay, and Venezuela) plus a minor fall for highly ranked Costa Rica.

Table 1.4 Percentile Rank for Rule of Law Indicator

An Initial Comparison with the Period of State-led Industrialization

The economic growth performance of Latin America since the 1980s is clearly weaker than that of the previous development phase. This is true even if we leave aside the “lost decade” of the 1980s. For the period 1990–2008, leaving aside also the recent crisis, the average of Latin America’s per capita GDP growth rate has been 1.8% per year, well below the growth rate of the period 1950–1980 (2.7%) and less than the average growth rate of the world economy. The growth performance of GDP per worker, a gross measure of productivity, is even worse: 0.7% per year for 1990–2008 vs. 2.7% in 1950–1980. This means that most of the increase in GDP per capita since 1990 has been the result of the demographic bonus resulting from the slowdown of population growth (from 2.7% to 1.5%) in the face of a still relatively fast growth of the labor force (2.6% per year, a rate similar to the 2.8% of 1950–1980) (see Ros, 2009).

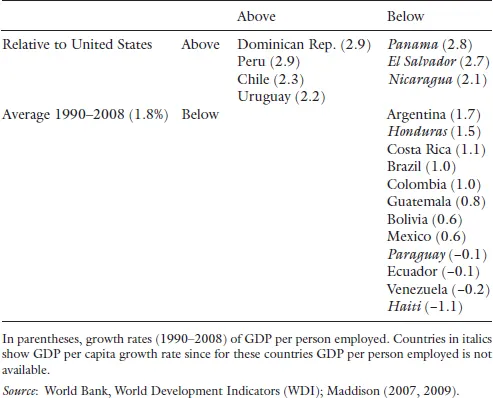

Table 1.5 indicates that only a few countries have experienced a dynamic growth of productivity at rates above 2% per year since 1990. Only four out of 19 countries (Dominican Republic, Peru, Chile, and Uruguay) had a better growth performance than in the period 1950–1980 while at the same time having an equal or faster growth than the United States for 1990–2008. Most countries recorded growth rates below that of the United States and a poorer growth performance in 1990–2008 than in 1950–1980. This poor overall productivity performance is not due to the absence of new dynamic and highly productive activities; it is rather the reflection of the rising share of low-productivity informal activities, as the dynamic highly productive sectors were unable to absorb a larger share of the labor force (Ros, 2011).

Table 1.5 Growth Performance 1990–2008 (Relative to 1950–1980)

It is worth noting that, when looking across countries, there is no apparent relationship between the degree and timing of market liberalization and growth performance. The countries in the northwest box with two of the best performances are Chile, an early reformer, and the Dominican Republic, a late reformer. These two countries have also two very different macroeconomic frameworks: while Chile has an independent central bank and a structural balanced budget rule, the Dominican Republic has none of this (see Table 1.1). Interestingly, all of the fast-growing economies under state-led industrialization, with thoroughly liberalized economies, have now underperformed in relation to the past and the United States, with the major exceptions of the Dominican Republic and Panama. It also worth noting that this economic performance was affected not only by the poor results of the market reforms but also by worldwide macroeconomic turbulence. The collapse of growth during the lost decade of the 1980s was followed by a recovery in 1990–1997, although at a slower pace than during the years of state-led industrialization, and then by the “lost half decade” of 1998–2003. As a result, the relative position of Latin America in the world economy went back in 2003 to the levels of 1900 (see Ocampo and Ros, 2011). The combination of a new surge in external financing, the emergence of China as a new major purchaser of raw materials, and the increase in commodity prices, which had been absent since the 1970s, generated a new boom in 2004–2007, at a pace that was then more similar to that of the 1970s. The global crisis in 2008–2009 suddenly interrupted the recovery after 2003, bringing about a deep recession in 2009, second only to that of Central and Eastern Europe among the emerging and developing countries.

Causes of Slow Growth: Bad Governments or Good Governments with Bad Policies?

The factors explaining why some Latin American countries benefited more than others from the policy and institutional changes are to a large extent idiosyncratic. I will return below to this question. There were nevertheless some common factors behind the generalized failure to accelerate growth in the region, compared to the historical performance in 1950–1980. One such factor was a wrong diagnosis of the debt crisis. The reform overhaul was rooted in many policymakers’ view that the 1982 debt crisis was the unavoidable consequence of the years of trade protectionism and heavy state intervention that had marked—and in their view distorted—Latin America’s development during the postwar period. Thus, this crisis, which started with the Mexican moratorium of August 1982, was taken to be a crisis of the whole postwar strategy of state-led industrialization. In fact, this was simply wrong. In countries with a large public external debt, such as Brazil and Mexico, the source of the problem was unsustainable macroeconomic ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 Institutional and Policy Convergence with Growth Divergence in Latin America

- 2 Productivity and Growth: Stylized Facts and Kaldor’s Laws in Latin America

- 3 The Real Exchange Rate, the Real Wage, and Growth: A Formal Analysis of the “Development Channel”

- 4 The Dutch Disease, the Staple Thesis, and the Recent Natural Resource Boom in South America

- 5 Close to the Epicenter: Mexico and Canada during the Great Recession

- 6 Why Does the Mexican Economy Grow Less Than That of Chile?

- 7 Mexico—Looking Ahead: Macroeconomic Policy and Development Strategy

- Notes

- References

- Index