This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Oswald Mosley has been reviled as a fascist and lamented as the lost leader of both Conservative and Labour Parties. Concerned to articulate the demands of the war generation and to pursue an agenda for economic and political modernization his ultimate rejection of existing institutions and practices led him to fascism.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Mosley and British Politics 1918-32 by D. Howell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Apprenticeships

Mosley contested the December 1918 election as the Conservative candidate for Harrow. He had been selected the previous July. His military service and his facility in answering questions with detailed arguments had impressed party activists. In retrospect, Mosley would trivialise his attachment to the Conservative Party. ‘I knew little of Conservative sentiment and cared even less. I was going into the House of Commons as one of the representatives of the war generation… I had joined the Conservative Party because it seemed to me on its record in the war to be the party of patriotism.’1 The 1918 election was fought on novel terrain between combatants whose identities were often ambiguous. The electorate had been transformed. At the previous election, in December 1910, about 60 per cent of adult males had had the vote; post–war, the male exclusions were minimal. Most women over 30 now had the vote for the first time. Franchise expansion was complemented by a radical redistribution of constituencies, the first since 1885. Population shifts meant a notable increase in the number of suburban seats. This expansion was particularly significant in London and the south-east; its impact shaped the social geography of Mosley’s first electoral contest.2

The political regime, unlike many across Europe, had survived the war and could appear vindicated by victory. In contrast with this continuity, post-war political alignments were opaque and as yet indeterminate. The armistice was followed quickly by the announcement of an election. Most Conservative candidates and 150 Liberals sheltered under the umbrella of the Lloyd George Coalition. They benefited from the formal backing of Lloyd George and the Conservative leader Bonar Law; the so-called ‘coupon’ confirmed them as the accredited candidates of the ‘Man Who Won the War’. Many Liberals remained outside the Coalition Pale and often faced Conservatives who were armed with the coupon.

Arthur Henderson had been Labour’s representative in the War Cabinet until his acrimonious departure in August 1917. Thoroughly supportive of the war effort, Henderson had regarded himself as the custodian of Labour’s interests at the highest level of government. He reverted to his responsibilities as party secretary and led the party’s preparations for what he and many colleagues hoped would be an enhanced position in any post-war party system. The party’s structure was reformed; organisational change was complemented by a comprehensive programme, Labour and the New Social Order. Henderson’s actions in what proved to be the last year of the war perhaps revealed his sensitivity towards nuanced but potentially significant political shifts within the labour movement. Institutional reforms, an ambitious programme and an unprecedented number of candidates expressed the party’s heightened expectations. These were fed by franchise expansion, the unrealised expectation of electoral reform and rising trade union membership. Yet Henderson’s exit from office and the subsequent reforms had not definitively transformed Labour’s position with respect to the Coalition. Some Labour MPs had continued as ministers. The armistice posed a strategic choice for Labour. A special conference decided that the party should fight any election independent of the Coalition. Several Members responded reluctantly to the decisions by the party conference and their own trade unions that they should fight the election as an independent force. A handful refused and contested the election as couponed supporters of the Coalition.3

Labour independence involved the suppression of an alternative future that extended far beyond continuing Labour membership of the Coalition. Some Labour politicians and trade union leaders had expressed their support for the war through jingoistic and xenophobic rhetoric. Several were highly respectable union officials who were prepared to limit trade union demands and to suspend workplace practices in pursuit of military victory. They coupled such concessions with support for military conscription and lurid denunciations of German infamy and pacifist cowardice. The highly respectable were accompanied by more colourful characters. Ben Tillett had been a volatile pre-war critic of Labour moderation; as a super-patriot he won a Salford by-election in 1917 with the slogan ‘Bomb the Boche’. Such sentiments inspired some on the Radical right to dream of an alliance that could challenge liberal pieties. Alfred, Lord Milner, once the personification of social imperialism in South Africa, had been marginalised by the pre-war Liberal Government. His influence grew after the outbreak of war; as a leading figure in the Lloyd George Coalition he personified the wartime challenge to liberal politics. For him, war offered the prospect of a radical remaking of political alignments; Milner envisaged an alliance between a modernising elite and robustly patriotic Labour in pursuit of a collectivist agenda. From May 1916 several Labour super-patriots endorsed such a programme through the British Workers’ League. In 1918 they were forced to choose between Labour Party independence and a cross-class mobilisation for national efficiency that would be implemented by an interventionist state. The BWL became the National Democratic and Labour Party in mid-1918. Almost all supportive Labour MPs reverted to their old allegiance; the NDP became entangled in largely unproductive negotiations with the Conservatives; they sought Tory support in selected constituencies in a post-war election. A few would enjoy the benefit of the coupon. Milner’s agenda became no more than an electoral footnote, yet this suppressed alternative would have affinities with Mosley’s later response to economic crisis.4

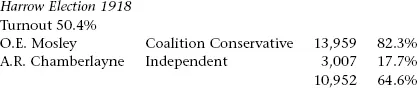

The Labour challenge did not extend to Harrow. The pre- war constituency had been a Conservative stronghold. Between 1885 and December 1910 only four out of eight general elections had been contested. The Liberals had been successful only in 1906 when defence of free trade had brought some Conservative votes temporarily into the Liberal column. The recent redistribution had made Harrow even safer for the Conservatives. Kilburn and Willesden, with their Liberal inclinations, had been removed. The new constituency was restricted to Harrow, Wealdstone, Wembley, Alperton and Sudbury. This slice of Home Counties suburbia had begun to expand pre-1914; between the wars it would grow rapidly, stimulated by the profusion of electric train services to central London. In 1918, neither a limited and uncertain local Liberalism nor a barely formed Harrow Labour Party could contemplate an intervention. Mosley’s only opposition came from within the Conservative ranks. A.R. Chamberlayne had been a three-times pre-war Unionist candidate. He stood as the candidate of the Harrow Electors’ League; he insisted that Mosley had been imposed on the constituency by the national party and was using his wealth to buy the seat. Against such complaints Mosley had a trump card. He was the official Coalition candidate and displayed Lloyd George’s imprimatur.5

Mosley’s first election address included proposals which would be significant elements in his later political agendas. Peace must be preserved abroad as a precondition for effective modernisation at home. The latter would be sustained by full employment at high wages based on buoyant levels of production. Educational opportunities would be extended and there would be provision of decent housing for all. He espoused meritocracy. The House of Lords must be reformed. ‘The hereditary principle in legislation was ridiculous.’ Mosley emphasised imperial preference as the basis for a cohesive empire that would be able to play an effective role in the League of Nations. His vision of modernity was underpinned by an insistence that the primary purpose of the British state should be the welfare of the British people. ‘Aliens’ were targeted. In 1918 these were predictably German but Mosley’s indictment retailed stereotypes familiar from earlier anti-Irish and anti-Semitic agitations. ‘They had brought disease amongst them, reduced Englishmen’s wages, undersold English goods and ruined social life.’6

His rhetoric wove together idealism, patriotism and the commendation of a state that would act with dignity and effectiveness.

At this moment when the deeds of their race had surprised the world with their glory, he asked them to regard the future with a world-wide vision. Whoever they sent to Parliament, send him with a national mandate not a parochial one… They had a colossal task before them. This country was seething with unrest, and they must see to it that the Government was a strong one and that the country was behind it, that it had a mandate from the country to reconstruct and build up our empire anew.

Discontent must be canalised, the disaffected must be integrated. Hence the Coalition’s programme ‘was Radical – some said Socialistic – in its advocacy of social reform’. Mosley used this challenge to justify the continuation of the Coalition. He belittled those outside the couponed ranks, ‘a small following of Mr Asquith, a minority (sic) of the Labour Party’; within the peculiarities of Harrow his target was Chamberlayne.

He had heard of some people who called themselves Independent whatever they might be. Men in the stone age were independent. An Independent in the House of Commons was like a lost soul… Surely a man who could find no place in the Coalition Party – composed of all shades of political thought – must be outside all things.

Although, or perhaps because, the candidates had few substantive differences on policy, the contest became personalised; Chamberlayne insisted that it was ‘an insult to the electorate to place before them a boy, the son of a baronet, wealthy and able to keep up the party organisation’.7

One observer claimed ‘a card with Lieutenant Mosley’s portrait was to be seen in most windows’. Yet as supposed evidence of overwhelming support the claim was an exaggeration. The same observer noted a lack of polling day excitement and attributed this to the relative absence of ‘the party element’.8 Such assessments were frequent in 1918. In Harrow the turnout was just over 50 per cent. Amongst those who voted, Mosley’s victory was emphatic.

Mosley went from Harrow to become the youngest Member of a parliament that offered a kaleidoscope of political identities. The Coalition administration, headed by a Liberal, included other Liberals in senior positions. The distribution of the coupon meant that the vast Coalition majority was preponderantly Conservative; the Government, whatever its Liberal notables, depended on Conservative votes in the lobbies. Many Conservative Members wished to defend their party’s pre-war identity and independence, but they might reflect that the party had not won a parliamentary majority fighting as an independent force since 1900. Others believed that new and urgent challenges meant that a return to pre-war alignments was a fantasy. Instead the Coalition, a product of wartime crisis, could be the basis for a new politics. The Prime Minister and at least some of his Liberal colleagues thought similarly.9

The 1918 election had reduced the un-couponed Liberals to a pitiful remnant; senior figures, most spectacularly Asquith, had been defeated. Whatever the wartime record of individual candidates, their lack of the coupon was fatal. Conservative backing for the war had been unambiguous. Unlike some Liberals, they had had no qualms in supporting illiberal policies as necessary for military success. Labour interventions further eroded Liberal support. However the growth in Labour candidacies in response to the extended franchise and the expansion of trade union membership had produced only a small increase in Labour Members compared with December 1910. Prominent figures associated with the anti-war Independent Labour Party, most notably Ramsay MacDonald, had been heavily defeated.10 The new Parliamentary Labour Party was even more thoroughly trade unionist than its predecessor. To its critics including many within the labour movement, the post-war PLP seemed sectional and unimaginative.

The pre-war Progressive alliance of reforming Liberals and Labour had been shattered. Some Liberal reformers, most notably Lloyd George, insisted that their Progressive credentials survived, despite sharing office with the Conservatives. Other Liberals, including prominent intellectuals and journalists, were antipathetic to Lloyd George. They resented the removal of Asquith from the premiership and damned his successor as unprincipled and unscrupulous. They hoped for an Asquithian revival; any reunification of the Liberal Party would have to be very much on their terms, with Lloyd George as a penitent supplicant. The place of Labour in such Liberal agendas remained unresolved. Some Liberals hoped for a return to pre-war collaboration; many others were more sceptical. Labour ambitions were far greater than before the war; any Progressive Alliance would reflect changed expectations and resources. Moreover, Labour’s relationship with increasingly ambitious trade unions made the party unattractive to many Liberals.11

Labour’s achievement in the 1918 election might have been modest in terms of seats won. However, the potential for Labour growth both politically and industrially preoccupied politicians. Despite the limited parliamentary advance, Labour’s vote had shown a significant if uneven expansion. Expectations that in a more favourable environment Labour would increase its parliamentary strength seemed justified by electoral successes during 1919. Parliamentary by-election and municipal victories suggested that this was indeed the forward march of labour. Labour’s immediate challenge went far beyond the routines of electoral politics. Trade unionists ,encouraged by economic buoyancy and fuelled by members’ heightened expectations, sought initially to advance beyond wartime gains; as the economic climate deteriorated from the winter of 1920–21 they sought to defend their recently achievements against employers’ counter-attacks. The challenge of ‘Direct Action’ was evident in the ‘Hands off Russia’ campaign, with many within the labour movement proclaiming their willingness to block the shipment of munitions to Soviet Russia’s Polish adversary. The prospect of coordinated industrial action by the Triple Alliance of miners, railwaymen and transport workers brooded over unrest in the coal industry. The rhetoric of ‘Direct Action’ decorated strikes that in reality were focused on wage increases and reduced hours. Advocates could claim legitimacy through a dismissal of the 1918 election as a fraudulent exploitation of patriotic sentiment that had produced an inflated and unrepresentative majority. The ethos of ‘Direct Action’ had affinities with the verbal and sometimes actual violence of pre-war conflicts; the fact of the Soviet Union and the fear that Red Petrograd might be replicated further west ensured that the containment of Labour, both industrial and political, became a dominant preoccupation. From the beginning of 1919 to the summer of 1921, Conservative, Liberal and many Labour politicians felt compelled to offer an alternative to the rhetoric and sometimes the reality of ‘Direct Action’.12

The remaking of political alignments became a critical element within any response. One possibility was that the Coalition offered the basis for a Centre Party that would unite all who favoured a strategy that combined resistance to the demands of ‘extreme’ labour with a programme of ‘realistic’ economic and social improvement that would offer an attractive synthesis for the expanded electorate. Forty Coalitionists, both Conservatives and Liberals, came together in a New Members’ Parliamentary Committee. Mosley was involved as joint secretary along with the Coalition Liberal, Colin Coote. He joined with other ex-combatants to express the hope that the priorities of former soldiers, not least their alleged belief in the need for a new politics, could be expressed through a Centre Party.13 Such aspirations, shared by some ministers, were suffocated by visceral partisanships. Many Coalition Liberals feared absorption by the Conservatives and preferred the, as yet, illusory objective of Liberal reunion. Many Conservatives from the beginning looked on the post-war Coalition and Lloyd George as temporary expedients. They remained unsure about Conservative prospects within the expanded electorate. Lloyd George might have explored the prospect for a cross-party coalition at the height of the constitutional crisis in 1910, but he was remembered amongst Conservatives as the most partisan of pre-war Liberal ministers. He was not only the man who had won the war; he had been the architect of the Peoples’ Budget and the scourge of the House of Lords. For many Conservatives his pre-war Liberalism had been indistinguishable from socialism; his oratory had been a demagogic exhibition of class enmity. As the prospects for a Centre Party withered in 1920, Mosley’s disenchantment with the Conservative Party and with significant government policies grew. The Foreign Secretary’s son in law was becoming ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- Overture: Guilty Men

- 1 Apprenticeships

- 2 Renegade

- 3 Elect

- 4 Networker

- 5 Minister

- 6 Critic

- 7 Explorer

- 8 Rejections

- 9 Options

- Notes

- Select Bibliography

- Index