eBook - ePub

Holocaust in Rovno: The Massacre at Sosenki Forest, November 1941

The Massacre at Sosenki Forest, November 1941

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Holocaust in Rovno: The Massacre at Sosenki Forest, November 1941

The Massacre at Sosenki Forest, November 1941

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In November 1941, near the city of Rovno, Ukraine, German death squads murdered over 23, 000 Jews in what has been described as "the second Babi Yar." This meticulous and methodologically innovative study reconstructs the events at Rovno, and in the process exemplifies efforts to form a genuinely transnational history of the Holocaust.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Holocaust in Rovno: The Massacre at Sosenki Forest, November 1941 by J. Burds in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Russian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Holocaust East versus West: The Political Economy of Genocide

Abstract: Three main elements distinguished the Holocaust in the East from the Holocaust in Western and Central Europe. First, the Holocaust in the East was presented to the public as a war of liberation from Stalinism, from Soviet “Jewish-Bolshevism.” Second, the Holocaust in the East was by and large carried out openly, in the presence of non-Jewish locals. In the West, most Jewish victims of the Holocaust were rounded up and forcibly transported in sealed trains to concentration camps in Central and Eastern Europe. This distance generated considerable space for deniability: sustaining the myth that Jews had been the victims of deportation and forced labor, not of mass annihilation. In contrast, a much smaller proportion of Soviet and East European Jews were exterminated in camps. While most Western and Central European Jews perished in the “industrial efficiency” of the camps, most Jews in the Soviet and Eastern European zones were shot, and the overwhelming majority were massacred at designated killing sites in or near their own homes by predominantly local ethnic nationalist militias who played the central role in their executions. Third, the Holocaust in the East mobilized a considerable proportion of the local population as co-perpetrators.

Burds, Jeffrey. Holocaust in Rovno: The Massacre at Sosenki Forest, November 1941. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. DOI: 10.1057/9781137388407.0007.

In early 1945, U.S. Military Intelligence—the Office of Strategic Services (OSS)—infiltrated several of its German-speaking secret agents into Prisoner of War (POW, or P.W.) camps of captured German soldiers. Although these agents did not unearth much valuable intelligence this way, the raw reports leave us with a fascinating snapshot of the popular culture of Wehrmacht soldiers near the brink of defeat, particularly

The influence of . . . Nazi propaganda which, apparently, has concentrated on the anti-Bolshevik line and, doubtless, has been very successful. If the P.W.s have grotesque ideas about the U.S.A., what they think about the U.S.S.R. is simply fantastic. A normal human brain ought to eliminate automatically this kind of fantasies, but Nazi propaganda has succeeded in transforming normal ways of thinking into morbid phantoms.1

U.S. Intelligence officials noted with dismay that “the influence of anti-semitisme [sic] is simply devastating.”2 As one German POW remarked to a secret informant: “The Poles will thank us for having exterminated their Jews.”3

World War II left a powerful imprint everywhere there had been a German occupation. Sixty years after the war ended, we have not begun to comprehend the nature and contours of that imprint, the depth and repercussions of occupation. In essence, what I am describing is a popular hate culture of the Żydokomuna, the alleged “Jewish-Communist conspiracy” that was used to justify genocide against Jews as part of the German-Ukrainian war of resistance against Soviet power.

Nazi propaganda against the Żydokomuna

Three main elements distinguished the Holocaust in the East from the Holocaust in Western and Central Europe. First, the Holocaust in the East was presented to the public as a war of liberation from Stalinism, from Soviet “Jewish-Bolshevism,” from the Żydokomuna. From the very first days of the German occupation in the East, witnesses noted the sudden appearance of ubiquitous leaflets and posters calling for a people’s war of liberation from “Stalinist oppression” and “Jewish-Bolshevism.” To legitimize German authority and recruit local support for German occupation policies, the “Jewish- Communist” element was anathematized in posters, leaflets, and hundreds of occupation newspapers that translated German messages of hate into the local vernaculars of the Soviet Union’s multiethnic communities.4 Leonard Dubinskyi, in Rovno, noted that after the Germans came, “there were posters everywhere.”5 A priest, Mikhail Nosal’, recalled that throughout Volhynia “people read these posters, they whispered about them, and gazed at all this ‘literary’ rubbish with disbelief.”6 In his memoir about wartime Brzezany, Shimon Redlich recalled that “both German and Ukrainian nationalist propaganda widely used the theme of Judeo-Bolshevism and alleged Jewish participation in the Soviet terror machine.”7 German and local nationalist leaflets alike scapegoated “Jewish-communists” for Soviet atrocities, real or imagined: “People [of Ukraine]! Know that Moscow, Poland, Magyars, the Jews—they are your enemies! Annihilate them!” This was a typical OUN-Bandera Ukrainian nationalist leaflet distributed widely during 1941 that openly advocated violence against Jews, ethnic Poles, and other ethnic groups. Other OUN-B leaflets advocated the same extremist views: “Exterminate the Poles, Jews, communists without mercy! Do not pity the enemies of the Ukrainian National Revolution.”8 Władislaw and Ewa Siemaszko found evidence that Ukrainian nationalists in Rovno (as elsewhere) had displayed their own posters calling for Ukrainian collaboration with the German liberators, and the liquidation of so-called foreign nationalities who had settled on Ukrainian soil as “pests” who ate Ukrainian bread. Twenty “foreign” nationalities were listed as enemies of Ukraine: Jews were first, Poles were second.9

Besides posters and public printed decrees, there were also occupation newspapers. In his own study of the Ukrainian occupation press, Mykhailo Koval found 190 German-sponsored Ukrainian language newspapers with a combined circulation of more than a million copies, plus 16 radio stations, local movie production facilities, and traveling exhibitions. The war against “Jewish-Bolshevism” was a central story in 576 of 700 issues of the occupation-era Ukrainian newspaper in Kiev, New Ukrainian Word (Novoe Ukrainskoe Slovo).10 Typical was this message from editor Ulas Samchuk in the newspaper Volyn, published in Rovno, on September 1, 1941: “The element that settled our cities, whether it is Jews or Poles who were brought here from outside Ukraine, must disappear completely from our cities. The Jewish problem is already in the process of being solved.”11 Occupation newspapers in the East regularly advocated the total annihilation of the alleged “Judeo-Communist” threat.

In his comprehensive survey of occupation-era newspapers, Sergei Kudryashov found nearly 200 Russian-language newspapers regularly published in German-occupied zones in Russia and eastern Ukraine. In his own study of the Ukrainian occupation press, John-Paul Himka found 160 German-sponsored Ukrainian-language newspapers and magazines. And hundreds of other Polish, Lithuanian, Estonian, Latvian, and Belorussian newspapers of the German occupation have likewise received attention from scholars. Circulation data from Poland show print runs of 10,000 to 200,000 copies of each newspaper, and millions of leaflets: the point is that a serious effort was made by the Germans to win the hearts and minds of civilians living in occupied zones of the Soviet Union.12

To take just one of hundreds of examples: in Latvia, attacks against local Jews were justified by media reports showcasing Soviet abuses. In the main Latvian-language newspaper of the German occupation, Teviia, throughout July 1941 there appeared numerous photographs of mutilated Latvian corpses from Riga’s main Soviet People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs (NKVD) prison, ostensibly innocent victims of “Jewish-Bolshevik” torture. A September 6, 1941 article in Teviia, entitled “Horrific Evidence from Excavated Graves,” presented forensic evidence to describe Soviet tortures in excruciating detail. In Rēzekne, according to the article, the Soviet NKVD tortured Latvian physician Dr. Paul Struve, removing the skin from his hands in boiling water, cutting out his tongue, and pounding nails into his heels. Hildegard Krikova had been beaten, tortured, and her breasts had been cut off. And the son of a local man, Yakov Terent’ev, had been found with the skin literally ripped from his back.13

Such detailed accounts were used to legitimize the German attack as a “liberation from Jewish-Bolshevism,” and appealed to all Latvians to support the regime by scapegoating all “Jewish-Communists” for such horrors. By vividly recounting the sufferings of local martyrs—these “victims of Soviet repression”—the accounts transformed the larger German war into every Latvian’s personal war against a monstrous enemy. Here and throughout the Soviet western borderlands, we find a curious ritualized vilification of Jews as communists, a vilification echoed in anti-“Jewish-Communist” posters and leaflets in shop windows and newspapers. The rituals themselves displayed the Jewish alliance with communism, and in this way justified and legitimized actions against Jews. In 1941 alone, approximately 72,000 of Latvia’s 80,000 Jews were massacred.

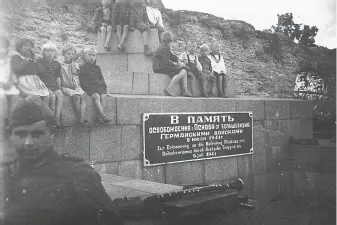

FIGURE 1.1 The Wehrmacht as an army of liberation from the Jewish-Communist threat. On the base of a destroyed Lenin statue in northwest Russia, the German occupying authority constructed a new monument with this plaque (in Russian and German): “In Commemoration of the Liberation of Pskov by the Germany Army, July 9, 1941”

FIGURE 1.2 On the base of a destroyed Stalin statue in eastern Ukraine, written in German and Russian, “The Bolshevik Terror Has Been Broken.”

Source: YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, Nusya Roth Collection, RG1871.

In ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction: The Intimacy of Violence

- 1 Holocaust, East versus West: The Political Economy of Genocide

- 2 Aktion: The Holocaust in Rovno

- 3 Aftermath: The Legacies of the Rovno Massacre

- Bibliography

- Index