eBook - ePub

Cybersecurity in the European Union

Resilience and Adaptability in Governance Policy

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Cybercrime affects over 1 million people worldwide a day, and cyber attacks on public institutions and businesses are increasing. This book interrogates the European Union's evolving cybersecurity policies and strategy and argues that while progress is being made, much remains to be done to ensure a secure and resilient cyberspace in the future.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Cybersecurity in the European Union by George Christou in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & European Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

The salience of cybersecurity in the European Union

Information and communications technologies (ICTs), in particular the Internet, have been an increasingly important aspect of global social, political and economic life for two decades, and are the backbone of the global information society today. Their evolution and development have brought many benefits for individuals, as well as a plethora of public and private institutions and actors; witness the positive impact of social networks on the uprisings in the Arab Spring in 2011, or the increased use of e-commerce across business and individuals. ICTs have also, however, brought the threat of serious cyber-attacks demonstrated in recent years through acts of cyber espionage and cybercrime within the virtual, networked ecosystem that we live in.

These have included, to name but a few high-profile cases, attacks on Estonia’s public and private institutions in 2007, Russian-sourced attacks on Georgian systems in 2008, the Stuxnet worm attack on the Iranian nuclear programme in 2009, the re-routing by a Chinese Internet service provider (ISP) of sensitive US government e-mail traffic to China, the WikiLeaks affair in 2010, not to mention attacks on several EU institutions in 2011 (the European Commission, the European Parliament). Beyond such high-profile attacks, reports of attacks on companies have also proliferated in the last few years (Net Losses Report 2014). Such events have underlined the vulnerability of ICTs and brought to the fore important policy issues that permeate the information security agenda. They have also highlighted the global and multi-dimensional nature of the information assurance problem – with recognition that security governance developed to combat the cyber threat must engage the many levels, actors, institutions and individuals involved within the cyber ecosystem.

In this context, the European Union (EU) over the past ten years has been developing its policies towards cyber threats, even though this has often been quite fragmented. The EU’s Internal Security Strategy (ISS, November 2010) and the Digital Agenda for Europe (2010) have provided the main broad guidance for its activities in this area in more recent times. However, the EU also produced more specific proposals through the European Strategy for Internet Security (ESIS 2011) and the Cybersecurity Strategy for the European Union (EUCSS 2013).

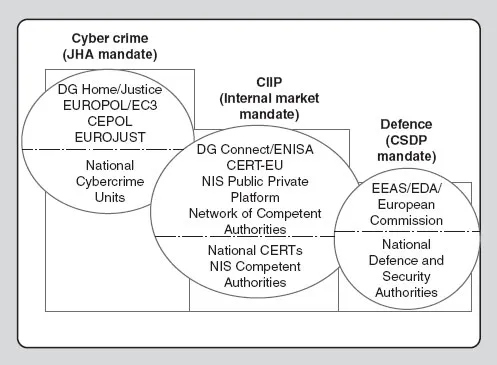

Institutionally, the European External Action Service (EEAS) plays the role of central coordinative node in agreeing on and projecting EU cybersecurity policy externally, whilst the EU Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT) fulfils the technical aspects of such a role internally. The Directorate Generals Connect (DG Connect) and Home (DG HOME) take the lead in developing policy in relation to Network and Information Security (NIS) and cybercrime, respectively, with the European Parliament also playing a key role within the policy process with regard to relevant Regulations and Directives. Beyond this, there are key EU agencies, including the European Defence Agency (EDA) which works on developing EU cyber defence, the European Network and Information Security Agency (ENISA) which works with relevant stakeholders to develop advice and recommendations on good practice in information security (including cybercrime), and with EU member states in implementing relevant EU legislation to improve the resilience of Europe’s critical information infrastructure and networks. Finally, Europol, and specifically the European Cybercrime Centre (EC3), focuses on the operational and strategic aspects of cybercrime (see Figure 1.1).

Cybersecurity is certainly one of the most salient problems on the EU’s political agenda, made even more pressing after cyber-attacks on the European Parliament, and the EU Commission and the EU’s Emissions Trading Scheme in March 2011, the latter at an approximate cost of €30 million in stolen emissions allowances (Leyden 2011). The estimated cost of cybercrime to the EU is €85 billion annually (EU prepares to launch first cybercrime centre, 2012) and certain analysts further estimate that within Europe up to 150,000 jobs could be lost to cybercrime over the next few years, in addition to the damage done to trade, competitiveness, innovation and economic growth (Net Losses Report 2014).

Such problems are not easily resolvable given their complex, often ambiguous and cross-jurisdictional nature, and the EU, although certainly making progress in the evolution of its policies in these areas, still has a long way to go before it can claim to have a unified, effective and resilient ecosystem for governing cyber threats. Indeed, whilst creating a comprehensive approach to cybersecurity within the EU has become a political priority with a renewed sense of urgency around the issue, there is still a lack of clarity on how cyber threats can be regulated and coordinated in governance terms in order to build sustainable and resilient platforms and systems. In short, whilst the EU certainly possesses many tools and mechanisms for addressing the cybersecurity issue, how it uses them needs to be developed, and the consistency and coherence across the institutions and actors involved improved, in what can only be described as an evolutionary security governance ecosystem.

Figure 1.1 The central pillars of the EU Cybersecurity Strategy (2013)

Source: Compiled from data within the Cybersecurity Strategy of the EU (2013, p.17).

Central questions and objectives of the book

It is the purpose of this book, therefore, to explain the evolution of the EU governance system for cybersecurity and provide a deeper understanding of how the EU can construct an effective security as resilience (see Chapter 2) with regard to questions of cyber threat. Moreover, it will facilitate provision of the answer to the central questions that this book seeks to ask:

• How can we characterise and understand the EU’s evolving ecosystem of cybersecurity governance?

• To what extent has the EU been able to construct a comprehensive approach to cybersecurity within the evolving ecosystem, and embed the necessary conditions for effective security as resilience?

• What is the nature of the resilient ecosystem emerging in the EU?

What is at stake within the EU space is significant. If the EU cannot facilitate the construction of the necessary conditions for security as resilience in cyberspace in the near and long term, then there is a danger that trust and confidence in the Internet will be eroded, and that the EU will remain vulnerable to cyber-attack and, importantly, unable to react and recover in an effective way. Improving the way in which the EU does cybersecurity is essential for the continued social, economic, financial and cultural benefits that citizens and businesses derive from the Internet and, more broadly, evolving ICTs. Moreover, it is critical if it is to achieve the objectives it has set for itself in the Digital Agenda for Europe (2010), and equally as significant, the driving force of such an agenda, the Europe 2020 strategy. Fostering trust and security in cyberspace then is not an option for the EU; it is a requirement and prerequisite for realising its own ambitions, promoting its values and (re)defining its identity in a dynamic global order that is increasingly reliant on digital interoperability and connectivity.

Theoretically and conceptually, work has been sparse in relation to analysing the EUCSS and emerging cybersecurity ecosystem. Broader research on cybersecurity has progressively increased from different perspectives (see Chapter 1), and certain authors have offered some insight into the EU approach through deploying the concepts of cyber power (Klimburg and Tirmaa-Klaar 2011; Sliwinski 2014) and resilience (Miriam Dunn Cavelty 2013). However, such works have not been comprehensive in their coverage or conceptual reflection on the emergent ecosystem of resilience within the EU and Europe. I am not arguing here that such approaches do not have anything to offer, in fact quite the opposite. Such works need further application and development if we are to reach a deeper understanding of how far the EU has travelled towards achieving effective security as resilience within its evolving ecosystem. The argument in this book is that an adaptable and flexible type of resilience should drive the EU’s approach to cybersecurity – that is, the EU should focus on developing the conditions for effective cybersecurity as resilience, through appropriate governance modes and mechanisms, for it to become an influential actor in cyberspace and a leader with regard to good practice in cybersecurity and its many different dimensions (see Chapters 2 and 6).

Given the above context, the objectives of the book are threefold:

• To provide a conceptually driven and comprehensive analysis of the EU’s emerging ecosystem for cybersecurity

• To employ a novel conceptual framework to the issue of EU cybersecurity through a fusion of resilience and security governance literatures

• To produce a deeper understanding of progress in the development of the EU’s approach and strategy to cybersecurity and the implications this has for effective cybersecurity as resilience in Europe and beyond

It is the contention of the author that such an undertaking is both timely and necessary, in particular given the hitherto lack of attention to the EU’s evolving practice in cybersecurity in an era of both internal institutional change and transition following ratification of the Lisbon Treaty (2009), and increasing security challenges in cyberspace, whereby citizens, governments, business and other actors are increasingly threatened (perceived or real) – culturally, financially, economically, politically and strategically. Whilst there are certainly many ideas ‘out there’ evolving through deliberation and discussion on what works best for effective cybersecurity, and the European Commission and other EU agencies such as ENISA are proactive in developing common definitions of problems (what is cybersecurity) and solutions (what is meant by resilience, types of public–private partnerships in cybersecurity), this book aims to assess how the main pillars of the EUCSS – cybercrime, network and information security (critical information infrastructure protection) and cyber defence (Chapters 5 and 6) – are working and pulling together to construct a more resilient and common understanding and practice related to cybersecurity. In addition, it seeks to place this in the context of the global more broadly (Chapter 2), and transatlantic cooperation more specifically (Chapter 7). Furthermore, it explores national resilience through offering an in-depth analysis of what is considered an advanced EU member state – the UK – in the area of cybersecurity (Chapter 4).

Certain clarifications need to be added and parameters made clear before outlining the structure of the book. The first relates to what sort of role the EU can realistically play in cybersecurity given that it touches upon many issues of national sensitivity and security. The EUCSS recognises that ‘it is predominantly the task of member states to deal with security challenges in cyberspace’ (EUCSS 2013, p.4), but also that the EU has a key role to play as an actor in itself. To this end, it is clear that the EU can be a facilitator and platform across the different realms of cybersecurity creating the necessary conditions for an effective culture of cybersecurity to emerge within member states – and critically, working with member states – weak and strong – in order to construct the minimal standards and skills – legal, technical, political, economic, strategic and operational – required for the EU to develop as a resilient actor and ecosystem in relation to cybersecurity. Not only this, the EU can act as an effective regional node for the exchange of good practice across the member states – and internationally, through the evolution, promotion and projection of principles and norms for Internet governance, including critical issues of cybersecurity. Indeed, given the borderless and transnational nature of cybersecurity and the external reach and influence of the EU, it has a critical role to play in creating a culture of resilience and cybersecurity not only in Europe, but also globally.

The second relates to the ongoing debate about how to define cybersecurity and its various dimensions – cybersecurity, cybercrime, cyber espionage, cyber terrorism, cyber hacktivism and so on. Whilst this has become a topic in and of itself for some scholars (see, for example, Di Camillo and Miranda 2011), and many regional and international organisations and agencies provide varied definitions, I do not intend to engage in the debate explicitly within this book. This is not to say that definitions are not important, but rather that any such discussion will be embedded within the relevant analysis and discussion in the themes visited in each chapter. Indeed a central part of the analysis will focus on the emergence (or not) of common definitions and understandings across the different dimensions of cybersecurity, with the starting point being definitions adopted by the EU (including relevant EU agencies) and its member states. Cybersecurity, in this instance, is defined by the EU in broad terms, with the definition of cybercrime much more focused in nature (see Box 1.1). Cyber defence is not defined within the EU documents given the sensitivity among member states on this issue, and the reluctance of certain member states to participate given their own cyber defence strategies (see Chapter 6). This is also why cyber defence, unlike cybercrime and NIS, falls under the intergovernmental Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) mandate and not within the EU’s exclusive or shared competence.

Box 1.1 European Union definitions of cybersecurity and cybercrime

Cybersecurity: ‘the safeguards and actions that can be used to protect the cyber domain, both in the civilian and military fields, from those threats that are associated with or that may harm its interdependent networks and information infrastructure. Cyber-security strives to preserve the availability and integrity of the networks and infrastructure and the confidentiality of the information contained therein’

Cybercrime: ‘a broad range of different criminal activities where computers and information systems are involved either as a primary tool or as a primary target. Cybercrime comprises traditional offences (for example, fraud, forgery, and identity theft), content-related offences (for example, on-line distribution of child pornography or incitement to racial hatred) and offences unique to computers and information systems (for example, attacks against information systems, denial of service and malware)’

Source: EU Cybersecurity Strategy (2013, p.3).

Third, whilst the author acknowledges and accepts that the analysis of cybersecurity within any domain must be interdisciplinary for a more comprehensive account to emerge – that is, giving equal weight to the ‘physical layer’ (hardware), ‘logic layer’ (software and protocol) and content or ‘social layer’ (culture, human contact, ideas and policy) (Benkler 1998, 2007) – this book prioritises the latter, with an emphasis on the social and policy conditions for a security as resilience culture to emerge. In this sense, it provides a contextual analysis of policy evolution and security logics, and a contemporary analysis of practice and the implications this has for ensuring an effective security as resilience approach. Thus, those expecting to find in-depth analysis of technological and technical solutions to cybersecurity issues will most likely be disappointed (!); but it is the hope of the author that it will at least create further conversation across the different layers on the relationship between the policy, cultural and technical challenges of constructing a resilient cybersecurity ecosystem in Europe and beyond. Technical solutions, after all, are only possible if the appropriate legal and policy environment exists to implement them effectively.

Fourth, whilst the book offers comprehensive coverage on what are considered the three main pillars of the EUCSS, there are still many important aspects of EU and European cybersecurity that could not be covered. Thus the book does not delve into the minutiae of EU policymaking and internal cooperation, competition and conflict between EU actors and agencies. In addition, priorities outlined in the EUCSS (2013) such as developing industrial and technological resources for cybersecurity and establishing a coherent international cyberspace policy for the EU are only discussed implicitly throughout the book; with the latter international aspect analysed in depth to some degree with regard to the international context (Chapter 3) and the transatlantic partnership (Chapter 7). Beyond this, issues such as cloud computing security, smart technologies (cities, environment, devices and so on) and IT-enabled industrial control systems, to name but a few, are not covered in order to ensure an element of focus and depth to the c...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables, Boxes and Figures

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Conceptualising Security as Resilience in Cyberspace

- 3. Cybersecurity in the Global Ecosystem

- 4. National Cybersecurity Approaches in the European Union: The Case of the UK

- 5. The European Union and Cybercrime

- 6. Network and Information Security and Cyber Defence in the European Union

- 7. Transatlantic Cooperation in Cybersecurity: Converging on Security as Resilience?

- 8. Conclusions: Towards Effective Security as Resilience in the European Union?

- Notes

- References

- Index