eBook - ePub

Women's Voices in Management

Identifying Innovative and Responsible Solutions

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Women's Voices in Management

Identifying Innovative and Responsible Solutions

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Women's Voices in Management examines a wide array of women's voices across different geo-political, social and organizational contexts in management. Extant research provides clear evidence on gendering in organizations throughout all the ranks including top management.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Women's Voices in Management by Helena Desivilya Syna, Carmen-Eugenia Costea, Helena Desivilya Syna,Carmen-Eugenia Costea in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Women’s Voices in Academia

2

Academic Leadership in the Nordic Countries: Patterns of Gender Equality

Rómulo Pinheiro, Lars Geschwind, Hanne Foss Hansen and Elias Pekkola

Introduction

It is widely acknowledged that the Nordic countries rank highly when it comes to the role of women in the labor market. Equality of opportunity on gender grounds has been a central topic in the labor policy agendas of many Nordic governments since the late 1960s and the early 1970s. Notwithstanding this trend, studies reveal that there are still substantial gender imbalances in the academic profession, most notably when it comes to representation at the highest levels of the organization (institutional governance) and/or academic status. Thus, the rationale for this chapter is to take critical stock, both quantitatively and qualitatively, of the role of women in Nordic academia – Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland – with a special emphasis on their role at the highest governance and managerial levels. The chapter has three major aims. First, it will illuminate the key figures (official statistics and authors’ own data) regarding the gender split throughout the academic career path, as well as female representation in university senior management. Second, it will provide a comparison of policies – at the macro (government) and meso (case institutions) levels – aimed at reducing the gender gap within Nordic academia. Third, it will cast a critical light – by drawing upon new qualitative datasets – on the backgrounds and experiences of a number of senior female leaders at selected case institutions, with a particular emphasis on career trajectories and structural and cultural barriers. Hence, our chapter makes a direct contribution to understanding the role of gender dimensions in contemporary higher education (HE) systems and institutions.

A multiple case-study research design, validated by a mixed-methods approach (Bryman, 2006), is adopted. Data triangulation was achieved through analysis of major policy documents and official statistics (national levels but also Nordic, such as the Nordic Council), institution-level data from four selected case universities (one per country), and face-to-face semistructured interviews with four senior female academic leaders at various hierarchical levels. The interviews (in English or in the respective local language) lasted 45 to 60 minutes each, and were recorded and subsequently transcribed verbatim. An English summary of major findings per interview category (background and career trajectory, general experiences, supportive factors, major barriers) was circulated among the research team.

The chapter is organized as follows. The next section covers the concepts and theoretical premises used in the study. This is followed by an empirical section divided into four distinct parts: a) a comparative data analysis regarding the position of women in Nordic academia; b) a brief overview of governmental efforts to promote gender equality in HE; c) a stock taking of the institutional strategies and policies of four case universities in the region; and d) the firsthand experiences of senior leaders at selected institutions. Section 4 discusses the findings in light of the theory. Finally, we conclude by sketching the implications of the study and by providing suggestions for future research.

Conceptual backdrop

There is burgeoning interest in how universities, as organizations, are changing (Pinheiro and Trondal, 2014; Karlsen and Pritchard, 2013), including matters pertaining to institutional governance, such as the appointment of senior leaders (Engwall, 2014; Loomes, 2014). Academic appointment processes are ostensibly gender neutral in that they rest on meritocratic principles, most often translated as academic excellence and defined through the collegial peer-review system. In reality, however, many studies have shown that male norms and networks reinforce the male overrepresentation in academia (van den Brink et al., 2010; Husu, 2000) and that salary gaps (females at junior levels) exist (Lee and Won, 2014). Furthermore, it has been shown that the peer-review system has a tendency to disfavor women (Wold and Wennerås, 1997).

In studies of the career trajectories of women, the concept of “the leaking pipeline” has been used to illustrate how women tend to drop out along their careers (Pell, 1996; Dahlerup, 2010; Chesler et al., 2010). Another frequently used concept is the “glass ceiling,” a framework that emerged in the 1980s, referring to invisible obstacles that hinder women in making it to the top (Minor, 2014; Cortina, 2008). More recently, Bendl and Schmidt (2010) have advanced a new metaphor – “firewalls” – which, according to them, has greater utility since it helps identify discriminatory aspects that have remained hidden in the glass ceiling framework, and better reflects the inherent complexities of modern organizations and organizational life. In contrast to the glass ceiling framework, which focuses exclusively on structural issues (“having discrimination”), firewalls combine structural and process-related (“doing discrimination”) aspects, such as the role of context in the production and reproduction of discriminatory behaviors (ibid., p. 629).

In relation to these concepts, two major lines of explanation have been developed. The first is the time-lag thesis, which suggests that women will eventually be equal to men; it is merely a matter of time. The other, less optimistic, explanation is the iron law of patriarchalism, stipulates that there will never be gender equality; namely, inequality is constantly reproduced. This line of arguments suggests that the moment women dominate an organization, the organization’s status decreases (Dahlerup, 2010). When it comes to the specific context of the academic profession, there have been suggestions on how to improve gender equality through increased transparency in recruitment and promotion processes (van den Brink and Benschop, 2012). A transparent recruitment process enables people outside the organization to understand on what grounds an appointed person earned his/her job, making sure the appointment complies with the prescribed criteria (gender has not been a permissible formal criterion for quite some time). Furthermore, if it is clear who is accountable for an appointment, it is more likely that prescribed criteria will be adhered to, since there may be negative consequences for the people responsible if the criteria are not followed. In practice, however, efforts to implement this have shown weak results. According to van den Brink et al. (2010), recruitment and selection processes are “characterized by bounded transparency and limited accountability at best” (p. 1459). In practice, micro politics and gender practices often obstruct any attempts to promote gender equality in recruitment processes.

Another method of promoting gender equality within academia is affirmative action. Although the details of these arrangements may vary, the general idea is to reserve a number of positions for a group (in this case, women) that is structurally disfavored in appointments to similar positions. Affirmative action is thus understood to act in the interest of a whole category of subjects, and generally in the interest of society as a whole. So, if gender equality is not being accomplished in any other way, some argue that we must make use of affirmative action (Thornton, 1984). Arguments against affirmative action usually focus on its antimeritocratic nature, as it does not involve appointing the most excellent candidates. The problem is that what is considered excellent is permeated by male norms, thus disfavoring women. Another argument against affirmative action, which is sometimes invoked by women in, or applying for, higher positions, is that there is a risk that peers will be skeptical about one’s meritocratic value and competence.

Empirical section

This section is organized around four specific areas. We start by providing some demographic data. This is followed by a brief presentation of the national and institutional (selected cases) policy frameworks. Finally, qualitative data from the interviews with senior academic leaders are presented.

Women in Nordic academia

The Nordic Council data regarding gender representation in Nordic academia overwhelmingly show that women are systematically underrepresented at the highest levels of the academic profession, but significant variations exist from country to country (Norden, 2013). In Denmark, the gender gap increases exponentially from grade D (“lecturer”) and above1, in the form of a steep curve in both directions, ending at close to 85 per cent male representation at professorial level. This contrasts with the cases of both Finland and Sweden, in which gender parity is more or less achieved up to grade B (“associate professor”), with a massive underrepresentation of female academics at the professorial level (around 20% of the total). In Norway, female representation gradually declines up the academic career ladder, moving from 60 per cent females in the student population to about 40 per cent at grades C (“assistant professor/senior lecturer”) and B, ending with figures closer to those of Finland and Sweden at the professorial level (around the 20%–25% mark).

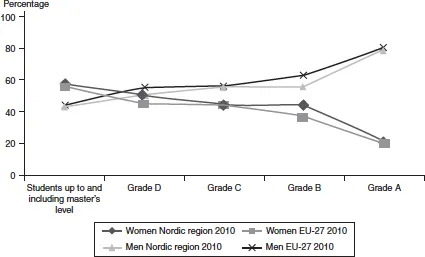

Taking a broader perspective, by comparing the Nordic2 and European Union regions (Figure 2.1, below), the data show that the situation of female academics in the former group slightly outperforms that of the latter at grades D (lecturer) and B (associate professor), with similar starting (students) and ending (professorial) points.

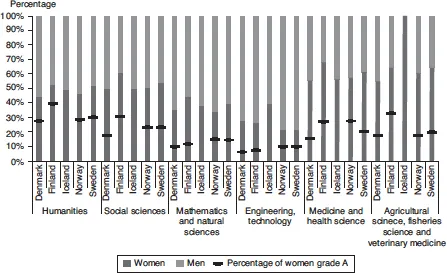

Coming back to the Nordic region, and in order to gain a more accurate picture of recent developments, it is worth looking at the gender distribution (doctoral degrees) and professorial status across major disciplinary fields (Figure 2.2, below). The data reveal that females are particularly underrepresented across the “hard fields” of the natural sciences and mathematics, as well as engineering/technology (traditionally male-dominated fields). As for the relationship between female representation at the discipline level and seniority (percentage of female professors), the data show a moderate correlation for most fields in which women are overrepresented or in parity, with the exception of the humanities, in which a positive correlation is detected.

Figure 2.1 Gender representation in Nordic academia versus EU-27, in 2010

Source: Norden (2013, p. 20).

Figure 2.2 Completed doctoral degrees by gender and discipline in the Nordic countries in 2010 and the percentage of women at grade A (professor level) in 2010

Source: Norden (2013, p. 21).

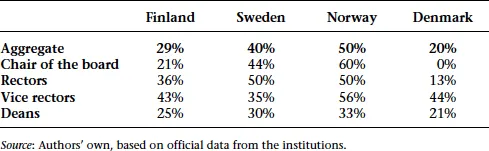

For representativeness in the managerial structures of public universities (Table 2.1), Norway leads the pack, with half of all senior positions at universities being occupied by a female leader. Sweden and Finland follow, and the “worst in class” is Denmark, in which only about one-fifth of all senior leadership positions are held by a female. The picture is similar at board level, where, at the time of writing, Denmark does not have any female as chair of the university board. The most even metric is for the vice rector(s) role, in which females account for an average of 45 per cent across the four countries. Female representation at the dean level varies from about a third in Norway and Sweden, to a quarter of all positions in Finland, and a mere one-fifth in Denmark. This is, we would argue, a function of the recruitment procedures used. Whereas the chairs of the board and in some cases the rectors are typically appointed by the board, deans are more often (albeit not always) elected by their peers, which raises some interesting questions about the relationship between the peer-review system/collegial decision-making model and gender equity (an aspect that has not yet been explored in detail in earlier studies).

Table 2.1 Female representation in university senior management (summer, 2014)

Governmental policy

Gender equality in Nordic academia has been at the forefront of the policy agenda since the 1970s (Norden, 2013). In Finland, the most concrete policy instrument for gender equality in the workplace, including the public sector and universities, is the gender equality plan – a statutory document that has to be prepared by every employer with 30 or more employees. According to the legislation, the gender equality plan must include aspects such as measures planned for introduction or implementation with the purpose of promoting gender equality and achieving equality in pay. Since the 1980s, a special delegation at the national parliament has focused on promoting equality in academia (ibid., p. 28). A special ombudsman has had the official function of promoting (and evaluating) the implementation of the Gender Equality Act. In 2010, the government decided to initiate a process for evaluating the government’s gender equality policy over the last decade, including its effects on education and research. Among other aspects, it is emphasized that in the future a major governmental priority will be to integrate gender issues into general science and university policy in Finland.

In Denmark, the theme of gender and academia has been on the policy agenda for many years. In spite of many think tanks and reports, very little has changed.3 In recent years, initiatives have been intensified as the government has implemented a number of national measures to ensure that women can make a research career. In 2004, the Danish science minister and the minister for equality established a think tank that aimed at recruiting more women to research positions. In 2008, partly as a result of Denmark’s globalization strategy, a special charter targeting the recruitment of women academics to senior managerial positions was established (Norden, 2013, p. 25). In 2009, the Danish minister for gender equality, as part of the “Perspective and Action Plan 2010” presented to parliament, highlighted the need for greater diversity in research and university management, including the recruitment of women to senior academic positions. Danish national gender policies for HE and research have mostly focused on women in research and women as leaders for research groups, with only very limited attention given to women in top leadership positions within academia.

Sweden has a long tradition of promoting gender equality and increasing the number of women in leading positions across sectors. Gender equality in HE has also, with varying intensity, been under scrutiny. Despite these efforts, gender differences have persisted. A large number of policy initiatives have been launched to address this. Recently, the Gender Equality Delegation (Jämställdhetsdelegationen) has produced a number of reports, some of which explicitly focused on the HE sector. In order to increase the nu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- Part I Womens Voices in Academia

- Part II Womens Positions and Roles in Work Life

- Part III Womens Voices in Joint Ventures: Entrepreneurship in Business and in Social Arenas

- Index