eBook - ePub

Scaling up Business Solutions to Social Problems

A Practical Guide for Social and Corporate Entrepreneurs

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Scaling up Business Solutions to Social Problems

A Practical Guide for Social and Corporate Entrepreneurs

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

A silent revolution is underway, as entrepreneurs challenge prevalent notions of business motives and methods to invent market-based solutions to eradicate social injustice. Yet many fail to succeed. Based on original research, the authors uncover why impressive solutions fail to scale up, featuring global case studies and practical solutions.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Scaling up Business Solutions to Social Problems by O. Kayser,V. Budinich in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Ethics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Solutions that work

chapter 1

Faces of poverty

This book is about children born in a favella in Rio or a rural village of Bihar, women and men who struggle to make a living and sustain their families. Their lives are so different from our lives in rich countries and yet so similar, filled with joy and pain, love and loneliness.

Their struggle invites our sympathy and admiration but also raises many questions. Does being economically poor mean being unhappy? Isn’t there happiness in slums? Are they really trapped in poverty, surrounded by insurmountable obstacles? Aren’t these sufferings partly self-inflicted? And even, are we right in using our own rich-world values to judge their lives?

We wonder who we would be if we had been born into these families. These lives touch us because they could have been ours.

The reader will find in the next pages some of the prevailing definitions of poverty as well as a summary of the attempts to put numbers on this multi-dimensional problem. But we wish to start this book by portraying three poor families from rural India, urban Brazil and rural Kenya.

Does being economically poor mean being unhappy?

A rural Indian family1

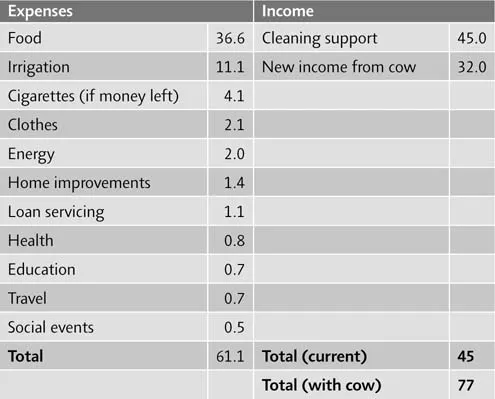

Bhogi Mukhiya, 45, and his wife, 35, have four children aged 14, 12, 10 and 5. They live in the village of Saurath in Madhubani District, Bihar. Bhogi has a job as a cleaner, his wife is a housewife. The entire family income is provided by Bhogi’s work: he earns 2700 Indian rupees (INR) or $45 per month;2 he also occasionally works on a farm and gets paid in kind, with wheat and rice.

ILLUSTRATION 1 Bhogi’s home and family

Boghi uses his government-issued Below Poverty Line Card to buy subsidized rations of food at half the standard price at the local grocery store. He spends over 80 percent of his income on feeding his family, a typical situation in poor households. The family has free access to drinking water at the village pump but they have to pay $11 per month for the irrigation water used to grow their own vegetables.

Only 2 percent of Boghi’s income is spent on electricity, buying it from a local diesel generator that powers one light bulb from 6 pm to 10 pm. The family also spends $2 per month buying kerosene, in particular to allow Boghi’s children to study in the smoky light of a wick fitted into a glass bottle.

No money is spent on cooking fuel as Bhogi’s wife and children spend several hours a day collecting the wood and leaves that fuel the traditional smoky chulha (cookstove). Boghi owns his house and pays no rent, but the walls are made of kuchcha (mud) and need to be repaired each year after the rain season, costing around $17. There is no sanitation in the house, and the family defecates in the neighboring woods.

ILLUSTRATION 2 Studying by candlelight

The youngest boy and the eldest daughter go to the local school. Admittance is free but parents have to spend $0.7 per month on books and notebooks. This $0.7 is an important expenditure but these illiterate parents are hopeful that their children will be better off in the future as a result of their education. Health expenses are roughly $10 per year. There are health-care services in the village or nearby. The local chemist gives consultations and sells medicine. The government runs a free Primary Health Clinic about 3 km away.

Boghi owes $58 at an interest rate of 2 percent per month (around 27 percent annually) to the village moneylender, whom he pays back in $1.1 monthly installments. In addition, this family of six spends $2 every month on clothes, $0.7 on travel, $0.5 on social events and $4 on cigarettes and other treats.

Recently, Boghi was given a valuable present: a cow (worth $170 on the market). Selling the milk will provide the family with an additional $50 for about eight months per year, nearly doubling the family’s earnings! It comes as no surprise that when asked what he would do with credit of $1000, Bhogi answers that he would invest in cows or buffalos and pay back the money by selling milk.

Today, approximately 35 percent of rural people in India are living at or below the income of Boghi’s family.

TABLE 1 Boghi’s family monthly P&L in current dollars

Notes: Average profit and loss (P&L): all non-monthly expenses or income have been computed annually, then divided by 12. Current total income: the net loss incurred before milk from the cow became available was bridged by recurring loans from informal sources, such as moneylenders or known people in the community, a prevalent practice of other families in Boghi’s village.

THREE DEFINITIONS OF POVERTY

“Low income, low levels of health and education, poor access to clean water and sanitation, inadequate physical security, lack of voice, and insufficient capacity and opportunity to better one’s life.”3 The World Bank

“If an individual possesses a large enough endowment or portfolio of capability he can, in principle, choose a specific functioning to escape poverty.” “Capability” refers to access to nutrition, health, education, shelter, clothing and information, but also refers to “freedoms” (from oppression, of religion, of expression), “security, and the degree of discrimination and social exclusion below which an individual is thought to be deprived.”4 Amartya Sen, Nobel Prize in Economics

“Individuals, families and groups in the population can be said to be in poverty when they lack the resources to obtain the types of diet, participate in the activities and have the living conditions and amenities which are customary, or are at least widely encouraged or approved, in the societies to which they belong.”5 Peter Townsend, Poverty in the United Kingdom (London, 1979)

An urban family in Brazil6

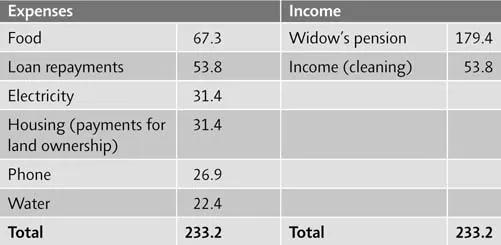

Pedrina da Costa Antonio, 55, is a single mother living in a slum in Paranaguá, south Brazil. Pedrina’s first husband died; her second husband left her, along with their daughter, now aged 16. Pedrina has also adopted two abandoned children, five-year-old old girl and a 17-month-old toddler.

ILLUSTRATION 3 Pedrina’s family in their new house

As a widow, Pedrina receives a monthly allowance of 400 Brazilian reals (R$) ($179) from the state. She occasionally adds to this income by working as a cleaning woman, providing her with R$120 ($54) each month.7

Her house is made of plank boards and old wood. It was hurriedly and illegally built after Pedrina’s previous house was destroyed in an accidental fire. It is connected to the electric and water grids, and to phone landlines. There are no sewers; waste water flows straight into a septic tank in the yard. Pedrina cooks on a wood stove, fuelled by old timber collected locally.

She struggles to pay $166 in monthly bills, over 60 percent of her average monthly income: $80 for utilities (electricity, water and telephone); $31 payable for seven years in order to become the legal owner of her house – her life dream; $54 to repay a loan. Fortunately, schooling and health are free public services – the nearby health center is quite crowded but the consultation is free.

This barely leaves $67, less than $2.3 a day to feed a family of four. This is a challenge when 1 kg of rice costs $0.7, beans $1.3 and 1 ltr of milk $0.8. Pedrina improves the family diet by collecting fruits and vegetables that the local supermarket throws away. Clothes and household goods are second-hand.

ILLUSTRATION 4 Pedrina and child in her new house

TABLE 2 Pedrina’s monthly P&L in current dollars9

Pedrina considers she is better off than her parents, because at least she will own her land and house. She is also hopeful that her children will make a better living, because they are going to school.

If she had money, she would fix the roof, find a house for her mother, and pay the bills on time. She would love to open a children’s day-care center, but has no idea how to make this dream come true.

Today, one in ten Brazilians live with equal or lesser earnings than Pedrina’s family.8 The United Nations estimates that by 2020 1.4 billion people will live in slums throughout the world.

MEASURING POVERTY

Metric

The complex reality of poverty is typically reduced by economists to one single number: daily consumption per capita measured in purchasing power parity (PPP) dollars.

To enable international comparisons, economists use the PPP exchange rate, i.e. “the rate at which the currency of one country would have to be converted into that of another country to buy the same amount of goods and services in each country.”10

As these numbers change over time, economists have been using 2005 as the base year for all their calculations. When you read about the $2 poverty line, it refers to the purchasing power of $2 for someone living in the USA in 2005.

In addition to technical challenges in producing accurate statistics, this measure only takes into account the cash economy, without considering that, especially in rural areas, subsistence producers consume part of their own production.

Poverty lines and BoP

The bottom of the (economic) pyramid (BoP) designates the poorest group in a population, living below a certain level of income or poverty line.

To set objectives for poverty reduction, the World Bank has established two poverty lines:11

- Extreme poverty: $1.25 PPP 2005 per day

- Moderate poverty: $2 PPP 2005 per day

The size of the market of the BoP is estimated by Al Hammond in “The Next Four Billion” (2005) with the same metric, but at a level set to $3,000 per year:

- BoP: $8 PPP per day

Note: C. K. Prahalad had defined the BoP as consumers earning less than $1500 PPP per year.12

A rural Kenyan family13

Boniface Kinungi is 38 and lives in the village of Gatundu, Thika with his son Dennis Mari, 14, and his two daughters Irene Wanjiku, 12 and Winnie Wanjiru, 9. Their mother died five years ago.

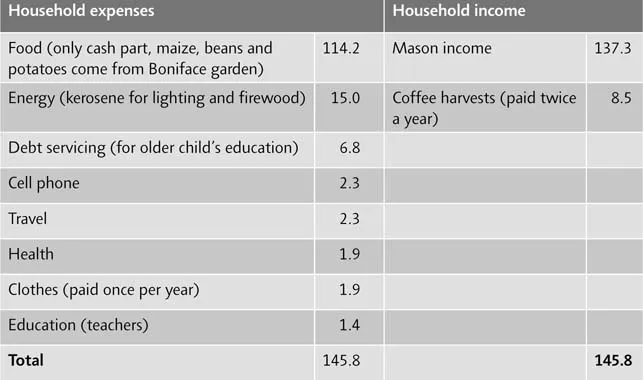

Boniface works as a mason 20 days per month on average, making around $137.14 He grows coffee on his one acre of land and sells his two harvests (200 kg of berries) to the local cooperative at $0.6 per kg, adding $8.5 per month.

The Kinungi family grows maize, beans and potatoes, but still spends over 75 percent of its cash on food bought from the local mini-shop. Usual meals are ugali (milled maize with vegetables, stew), githeri (a mixture of maize and beans), rice and chapati (flat bread, only during major holidays).

ILLUSTRATION 5 Boniface’s home and family

ILLUSTRATION 6 The kitchen

The family cooks on a traditional three-stone stove, using firewood bought for $10 per month. A small lantern popularly known as a karabai is the only source of light in the house, burning $5 worth of kerosene each month.

There is a shared pipe for water but it runs dry most of the year. All family members fetch water from a river that is said to be clean, spending two hours a day carrying four containers of 20 ltr.

Education is very important to Boniface, who only went to primary school. Dennis failed to join secondary school and attends a youth vocational training centre. To pay for the $120 two-year program, Boniface took out a loan from a “Ngumbato” (a merry-go-round group where contributions from all members are pooled together as savings from which members borrow in turn, offering lower rates than banks). He pays back $7 per month.

The primary school that Irene and Winnie attend is free, but each child has to pay $9 per year for the private teachers employed by the school to cope with the lack of government-employed teachers. Other recurring expenses are transportation to the local market and phone expenses for Boniface to enquire about employment opportunities. Health issues cost $23 per year, while clothes are purchased at Christmas for about $23.

TABLE 3 Boniface’s monthly P&L in current dollars

Notes: Average P&L – all non-monthly expenses or income have been computed annually, then divided by 12.

In addition to his land and house worth $4,300, Boniface owns a sheep that he rears for animal manure and eventual sale value. He plans to buy a grade milk cow to lower his expenses on milk ($4 per month) and sell the extra milk to processors. He hopes to save some of the $850 required to buy the cow – and to borrow the rest. His dream is to own ten dairy cows.

Today, approximately 55 percent of the Kenyan population is living at or below the income level of the Kinungi family.

DYNAMICS OF POVERTY

Since 1981, the proportion of people living below the $2 poverty line has been reduced from 55 percent to 35 percent of the world population but the number of poor people has barely been reduced from 2....

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of figures, tables and illustrations

- Forewords by Bill Drayton and Emmanuel Faber

- Acknowledgments

- List of abbreviations and acronyms

- About the authors

- Introduction

- Part 1 Solutions that work

- Part 2 Obstacles to scale

- References

- Select bibliography

- Index