eBook - ePub

Romantic Englishness

Local, National and Global Selves, 1780-1850

D. Higgins

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Romantic Englishness

Local, National and Global Selves, 1780-1850

D. Higgins

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Romantic Englishness investigates how narratives of localised selfhood in English Romantic writing are produced in relation to national and transnational formations. This book focuses on autobiographical texts by authors such as John Clare, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Hazlitt, Charles Lamb, and William Wordsworth.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Romantic Englishness by D. Higgins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism in Poetry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

‘These circuits, that have been made around the globe’: William Cowper’s Glocal Vision

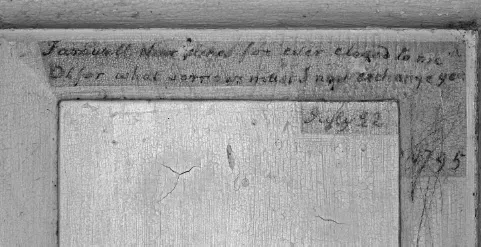

Farewell dear Scenes – for ever clos’d to me,

Oh for what sorrows must I now exchange you.1

On 22 July 1795, William Cowper wrote these lines on a window shutter at his home in Weston Underwood (Figure 1.1). Stricken by mental and physical ailments, the poet was about to move to Norfolk where he and his long-term companion Mary Unwin could be properly cared for by his cousin John Johnson. Given the grim melancholy that afflicted him during his final years, and Mary’s failing health, he may have felt that in moving away he was leaving behind the last source of pleasure available to him. The intensity of his attachment to his local environment is suggested by the fact that he writes directly onto the fabric of the house, as if that would allow a small part of his self to stay there forever. With customary wit, he chooses the most appropriate object on which to inscribe the lines: by moving away, he will be permanently shutting out the ‘dear Scenes’ of his past. It is apparent from the poet’s letters that these feelings of attachment were long-standing: thus he writes to John Newton in July 1783 that ‘the very Stones in the garden walls are my intimate acquaintances; I should miss almost the minutest object and be disagreeably affected by its removal […] [were I to] leave this incommodious and obscure nook for a twelvemonth, I should return to it again with rapture’.2 As we will see throughout this study, the local environment, however meagre or uncomfortable, elicits a surprisingly powerful emotional response. Cowper might, therefore, be seen as a paradigm of Romantic localism: an author whose intense subjectivity was combined with a powerful attachment to his ‘native place’ (Letters, III, 43). However, although he often celebrated the virtues of sequestration from ‘the world’ in an ‘obscure nook’, the highly localised self found in his letters and poems is consciously incorporated into a broader national and transnational context. Through his reading of exploration narratives and newspapers, he is able to present what I call a ‘glocal vision’. Rather than separating the local and the global, Cowper is fascinated by their interconnections and the ways in which one can be simultaneously at home and abroad. His understanding of these connections is modelled through different forms of circulation. In ‘Charity’ (1782), the free circulation of global commerce enables the productive exchange of resources between nations, and their consequent moral improvement. But lurking behind this is the spectre of the slave trade: a circulation of suffering that denies the freedom and equality of human beings in the eyes of God. In his letters of 1783–4 and in The Task (1785) – texts which are troubled by Britain’s defeat in the American Revolutionary War and its imperial adventures in India and the South Seas – Cowper takes a sceptical view of the value of all material forms of global circulation. And yet, while valorising retirement from the public world, he is also fascinated by the possibility of vicarious imaginative circulation, allowing the autobiographical self to follow the journeys of explorers and colonists from the comfort of his Olney fireside. These models of transoceanic movement back to a starting point are complicated by Cowper’s more linear sense of his own spiritual journey. Initially this is a movement from confusion and alienation to a comprehension of God’s love, in the tradition of Protestant spiritual autobiography, but in later texts it potentially becomes a journey away from God and to perpetual damnation.

Figure 1.1 William Cowper, ‘Lines Written on a Window-Shutter at Weston’ (1795). Reproduced with the kind permission of the Cowper and Newton Museum, Olney, Bucks.

Despite valuable recent work by Mary Favret, Kevis Goodman, and Jon Mee, Cowper’s relationship to British Romanticism is still underexplored. Vincent Newey’s important 1982 book, which presents the poet as a ‘Romantic’ and ‘Modern’ beset by existential crisis, has not had the influence it deserves.3 Newey only touched on Cowper’s politics, which were explored more fully in a subsequent article by W. B. Hutchings that suggested that Cowper was not a withdrawn and ‘self-obsessed poet’, but had a ‘sharp perception’ of the ‘public world’.4 Newey responded in an essay that examined the relationship between Cowper’s poetry and national politics, contrasting the public engagement of the moral satire ‘Table Talk’ (1782) with what he saw as the Romantic individualism of The Task and other later poems: ‘it is in the drama of private desert places, not national or political aspiration, that Cowper discovered his true heroic “song”’.5 I think that this claim needs some nuancing: clearly The Task valorises withdrawal from the world (partly as a result of political disappointment), but Hutchings and Newey primarily see the ‘public world’ in relation to national politics, and therefore do not fully recognise the more subtle global connections that inflect Cowper’s representation of private retirement. Existential crisis, as this book will consistently argue, cannot be understood separately from how the self is constructed in relation to real and imagined geographies.6

Cowper was popular among the provincial middle classes, and played an important role in shaping ideas of domesticity in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. As Leonore Davidoff and Catherine Hall note, he ‘validated a manliness centred on a quiet rural domestic life rather than the frenetic and anxiety ridden world of town and commerce’.7 This passage from Book IV of The Task is often presented as emblematic:

Now stir the fire, and close the shutters fast,

Let fall the curtains, wheel the sofa round,

And while the bubbling and loud-hissing urn

Throws up a steamy column, and the cups

That cheer but not inebriate, wait on each,

So let us welcome peaceful evening in.8

This does indeed seem to represent an ideal of gentle, sociable domestic retirement, with the closed shutters and curtains acting as a barrier to the outside world. But the inwardness of Cowper’s writing – its tendency to what Newey calls ‘scale-reduction’ – often exists alongside a more outward-looking tendency.9 Therefore recent scholarship has begun to explore the complex relationship between the domestic, the national, and the global in his work. Karen O’Brien has usefully examined ‘the special quality of Cowper’s imperial awareness which permeates and modifies his sense of what it means to be “still at home” in the country’.10 This insight is fundamental to my approach in this chapter and I agree with her more recent claim that The Task represents ‘the late eighteenth century’s most searching attempt to explore the impact of the global on the domestic, from British politics and patriotism right down to Cowper’s intimate, subjective experience of life in a small Buckinghamshire town’.11 Perhaps the most significant way in which global events were brought to Olney and other provincial towns was through reading the daily newspaper, as presented at the opening of Book IV of The Task. Kevis Goodman and Mary Favret have in different ways explored how The Task seeks to translate the chaos and heterogeneity of the news into a poetry of the present.12 And Jon Mee has highlighted how Cowper ‘domesticates and gentrifies the news into the idea of a national conversation’, rightly emphasising that this was a religious conception: ‘an imagining of Protestant and British community raised above the sense of wider corruption’.13 This chapter develops these approaches to Cowper. In particular, it nuances his conception of nation and investigates the crucial religious aspects identified by Mee. It also presents Cowper’s poetic vision alongside the more informal autobiographical utterances of his letters. These texts, which have had little critical attention, are concerned with connecting the local to the national and global through their accounts of British politics, the American Revolutionary War, and, perhaps most interestingly, Cowper’s reading of travel literature.14 If we are fully to understand the extent and ramifications of Cowper’s glocalism, the letters and poems need to be read alongside each other. My engagement with the letters acts, therefore, as a bridge between my initial analysis of the utopian ‘Charity’ and my concluding discussion of the complex glocalism of The Task.

‘Charity’

‘Charity’ is one of the eight long ‘moral satires’ in rhyming couplets that formed the bulk of Cowper’s Poems of 1782. It has not been well served by critics; for example, it does not even get a mention in Newey’s chapter on the moral satires. And yet it is a crucial text for understanding the relationship between individual, nation, and empire in Cowper’s autobiographical writing later in the 1780s. Early on, the poem contrasts Captain James Cook, who had died in Hawaii three years earlier, with the sixteenth-century Spanish Conquistador Hernán Cortés as different paradigms of colonial exploration. As is typical of the period, Cook is treated hagiographically: he is simultaneously heroic and humane, the best possible representative of the nation across the world, who ‘steer’d Britain’s oak into a world unknown, / And in his country’s glory sought his own’.15 Cowper may be drawing here on Pope’s glocal vision in ‘Windsor-Forest’ (1713), which describes how trees are transformed into ships that ‘Bear Britain’s Thunder, and her Cross display, / To the bright regions of the rising Day’.16 He was to return to this theme himself in ‘Yardley Oak’ (composed 1791), in which the oak is fortunately spared when it ‘might have ribb’d the sides of plank’d the deck / Of some flagg’d Admiral’.17 In ‘Charity’, ‘oak’, of course, is a synecdoche for Cook’s ship, but it is also a synecdoche for Britain as an imperial power across the globe. Cook’s ship is a piece of the nation, wherever it is in the world. At the same time, however, Cook is not an aggressive imperialist, but a monogenist who understands that, despite cosmetic differences, all human beings have the same Adamite ancestry and that their freedom (‘the rights of man’ (l. 28)) must be respected: ‘Nor would [he] endure, that any should control / His freeborn brethren of the southern pole’ (ll. 33–4). He exemplifies the charitable face of the British Empire. In contrast, Cortez – and the Spanish empire he represents – is motivated only by greed and violence. The decline of Spain is divine punishment for their brutal treatment of indigenous peoples and destruction of the environment (‘thou that hast wasted earth’ (l. 69)).

‘Charity’ goes on to present a utopian vision of what a globalised world should look like, emphasising how nations are connected through reciprocal exchange:

Again – the band of commerce was design’d

T’associate all the branches of mankind,

And if a boundless plenty be the robe,

Trade is the golden girdle of the globe;

Wise to promote whatever end he means,

God opens fruitful nature’s various scenes:

Each climate needs what other climes produce,

And offers something to the gen’ral use;

No land but listens to the common call,

And in return receives supply from all;

[…]

These are the gifts of art, and art thrives most

Where commerce has enrich’d the busy coast:

He catches all improvements in his flight,

Spreads foreign wonders in his country’s sight,

Imports what others have invented well,

And stirs his own to match them, or excel.

’Tis thus reciprocating each with each,

Alternately the nations learn and teach;

While Providence enjoins to ev’ry soul

A union with the vast terraqueous whole. (ll. 83–92, 113–22)

Paradoxically, trade binds together the ‘boundless plenty’ of the world.18 It is designed by God to induce fellow feeling between humanity’s different ‘branches’, and to allow for emulation and improvement through imports and exports between nations. Luxury – ‘the gifts of art’ and ‘foreign wonders’ – and virtue are not therefore in opposition, but are actually two sides of the same coin. Global providence not only connects individual souls and nations, but brings humanity into a unified relationship with the endlessly bountiful global environment, ‘the terraqueous whole’. Thus, the poem goes on to suggest, the work of traders and explorers is to be celebrated: they spread ‘opulence’ (l. 130) across the world and, more importantly, bring ‘God’s love, to pagan lands’ (l. 136).

What threatens this paean to the power of free commerce to elevate, improve, enrich, and Christianise humanity is, of course, the transatlantic slave trade. This manifests the wrong sort of global circulation and ‘binding’ because, rather than improving the lot of human beings in general, it destroys the ‘bonds of nature’ (l. 142) and allows a few to...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 ‘These circuits, that have been made around the globe’: William Cowper’s Glocal Vision

- 2 Local and Global Geographies: Samuel Taylor Coleridge and the Wordsworths

- 3 Labouring-Class Localism: Samuel Bamford, Thomas Bewick, William Cobbett

- 4 John Clare: The Parish and the Nation

- 5 William Hazlitt’s Englishness

- 6 Charles Lamb and the Exotic

- 7 ‘The Universal Nation’: England and Empire in Thomas De Quincey’s ‘The English Mail-Coach’

- Notes

- Bibliography of Works Cited

- Index