eBook - ePub

Single Life and the City 1200-1900

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Single Life and the City 1200-1900

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

By taking on a long-term perspective, a large geographical scope and moving beyond the homogeneous treatment of single people, this book fleshes out the particularities of urban singles and allows for a better understanding of the attitudes and values underlying this lifestyle in the European past.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Single Life and the City 1200-1900 by Isabelle Devos, Julie De Groot, Ariadne Schmidt, Isabelle Devos,Julie De Groot,Ariadne Schmidt, Isabelle Devos, Julie De Groot, Ariadne Schmidt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Gender Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Constraints and Opportunities

1

Working Alone? Single Women in the Urban Economy of Late Medieval Flanders (Thirteenth–Early Fifteenth Centuries)

Peter Stabel

The thirteenth and fourteenth centuries witnessed dramatic changes in the family structure of Europe. The nuclear family and the companionate household became the main features of societal organisation in western Europe. Some scholars go even as far as linking the divergent economic development of the West to these drastic changes as the so-called European Marriage Pattern (EMP) gradually got hold.1 Whether the emergence of these phenomena can be linked to the demographic and social upheaval following the Black Death, or whether they were caused by other variables (changing economic organisation, changing power relations, etc.), the breakthrough of the household as structuring organisation of society must have dramatically changed the social position of single women in the city, and influenced their place in the organisation of the economy.

As I have argued elsewhere, in the main urban industry of the Low Countries (the manufacture of woollen cloth, which employed in some industrial cities up to 60 per cent of the population), there are reasons to assume that women were ousted from some of the key manufacturing stages such as weaving as early as the late thirteenth century. The independent economic activity of women gradually was banned, forcing them to take up less rewarding occupations such as spinning. Paradoxically wealthier women could still be active on their own as an entrepreneur.2 Women were also increasingly encapsulated in the household as an economic unit. The guilds, which in most cloth manufacturing cities came of age from around the middle of the thirteenth century, seem to have been crucial in this process. There is fierce debate between optimists and pessimists about the agency of guilds in deciding the declining position of women on the labour market during the late medieval and above all the early modern period. The latter point at the male-dominated craft guilds for having been a crucial player in the marginalisation of women on the labour market across the late medieval period; the former doubt whether the position of women changed for the better or the worse in this period and as a result they target guilds less as instrumental in the elaboration of patriarchal dominance. Most empirical evidence for the late medieval period (guild matriculation, guild accounts, citizen’s matriculation) indeed points at a relatively marginal position of independent (single) women in most retailing guilds (the mercers being the important exception) and in all the manufacturing guilds.3 At the same time, however, the EMP with its high age at marriage for women is said to have increased opportunities for independent employment for women (life cycle servants, etc.) while, because of labour shortage after the Black Death, other work opportunities must have risen as well. These two developments seem to be contradictory, however. If women were increasingly banned from participating in the formal labour market and if they were either encapsulated in the patriarchal household or forced to work only in less well paid and low-status occupations, the position of single women (in the period before marriage) cannot have been as strong as suggested by De Moor and van Zanden.

Sadly, sources from this early period are notably scarce. Only normative sources, statutes and ordinances, which are preserved for the best documented manufacturing cities of Flanders, Douai and Ypres, allow to examine how these changes strongly influenced the opportunities for women to be active as independent workers in particular high-status manufacturing stages of the key industry, which was the manufacture of woollen cloth. Combined with tax records, which only start in the late fourteenth century, they allow nonetheless to unravel the chronology and the mechanism behind these changes.

This chapter, therefore, has a double goal. On the one hand, it wants to investigate on the basis of taxation records in some manufacturing centres of late medieval Flanders (Ypres, Bruges and the small industrial town of Eeklo) from the period just after the first outbreaks of the Plague around 1400, how single women were economically active. On the other hand it tries to assess how economic regulation by guilds and towns affected in the preceding period (a crucial period of industrial and commercial change) the opportunities for work for women as independent workers in general, and, therefore the influence of long-term shifts in the opportunity for doing “independent” labour activity (and implicitly affecting the possibility of single women to sustain themselves in urban society).

Single women in the city

It is very hard to get an idea of the position of single women in the pre- and post-Black Death era in urban society in the Low Countries. Very little is known about the number of single women in the cities of the Low Countries before the final decades of the middle ages, let alone about the economic sectors in which they worked and where they earned their income. Empirical research into single women in the medieval cities of the Low Countries has focused almost exclusively on widows and their specific status in the guild system. As such widows were, of course, a substantial part of the group of single women in the medieval city. But their relatively free juridical status and the fact that they could continue the enterprise of their deceased husbands gave them a very specific place in urban society.4

The only source to present a more or less reliable image of the share of single women in society is taxation. Despite all the usual caveats (the very poor were, of course, excluded from paying taxes; certain categories such as beguines and religious women in the Third Orders or other semi-religious communities do not appear either, etc.), taxation already gives a clue as to the number of households headed by women, and usually also about the number of widows. Sadly, very few lists of the thirteenth and fourteenth century have survived. Direct taxation was not a regular form of income in the larger cities of the Low Countries, indirect taxes or excises on beer, wine, grain and other commodities being the preferred instrument of urban finance. The few surviving examples are, therefore, mostly situated in extreme circumstances of political or financial turmoil. Urban administrations were less familiar with this type of taxation and in these circumstances the tax assessment of every household can only be a very crude estimate. Still, the lists provide figures for those households which were considered as being able to pay up.

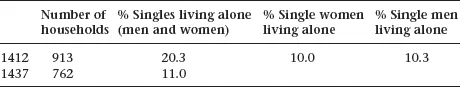

As far as I know, there is only one example of a medieval urban tax list in medieval Flanders that allows reconstructing the number of singles, that is people heading their own household and not living together with their spouse at a given time. The tax lists covering a substantial part of the city of Ypres in the early fifteenth century – the data cover one of the four substantial quarters (vierendeelen) of the city, the so-called quarter of the Common Craft (Ghemeene Neeringhe) were used by Henri Pirenne in a ground-breaking article published in 1903. The data point at very high numbers of singles living in this quintessential cloth manufacturing city.5 In 1412 more than one-fifth of the city’s households (and 6.3 per cent of the population) were indeed singles, and almost half of them were single women (Table 1.1). A quarter of a century later, however, the proportion of single households in the same quarter of the city had dropped to a mere 11 per cent of all households (and 3 per cent of the quarter’s population). In this period the city of Ypres, which saw the success of its cloth manufacture dwindle almost year by year, lost more than 12 per cent of its total population. Unfortunately, the data presented by Pirenne do not allow comparing with the other quarters as the sources were destroyed in the First World War.

The Ypres data point nonetheless at the high volatility of singles in the medieval cities. The figures of households do not include the majority of domestic servants, as these tended to live in the house of their employer. A later tax list in Ypres, dating from 1506, however, does mention 126 live-in female servants (joncwijven) and 98 in-living male servants (cnapen) or a total of 10 per cent of the population at that time. If domestic servants are to be considered as unmarried singles a comparable number of c.10 per cent of the total population should be added to the figures mentioned above. If we are to assume a similar figure for the earlier tax lists – economic circumstances had, however, shifted dramatically in the course of the fifteenth century – this would mean an additional 177 female domestic servants and 118 male servants in 1412. Added to the 91 single women and 94 single men, this makes a total of 16.3 per cent of the total population.

In other cities, tax lists do not give as much detail about single households. Usually they only mention the name of the head of the household and the amount of the tax assessment; and only occasionally additional information about occupation and residence are given. For the period under consideration, the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, only tax lists from the end of the period have survived. In Bruges various tax lists from the period 1394–96 were published in the 1970s. They show for some of the city’s “sixths”, the so-called zestendelen (Bruges was divided into six administrative districts) a large proportion of female households (household headed by a woman).6 The tax lists usually do allow distinguishing between women who were unmarried or separated from their husband (sometimes it is indicated whether children were present) and widows, whose juridical status is always mentioned. The same material exists for the smaller cloth town of Eeklo (and its rural district of Balgerhoeke), about 20 kilometres to the south-east of Bruges.

Table 1.1 Percentage of single women in Ypres (quarter of Ghemeene Neeringhe), 1412 and 1437

Source: Pirenne, “Les dénombrements”, 12–22.

For Bruges, the zestendelen of St James, St Nicholas and Our Lady have on average 14 per cent female households, while in the small cloth town of Eeklo this proportion is slightly higher at 17 per cent (Table 1.2). In Eeklo’s rural and proto-industrial (cloth manufacturing) dependency, Balgerhoeke, the percentage is substantially higher, reaching almost one-fifth of the number of households. This would sugg...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction: Single and the City: Men and Women Alone in North-Western European Towns since the Late Middle Ages: Ariadne Schmidt, Isabelle Devos and Bruno Blondé

- Part I Constraints and Opportunities

- Part II Group Experiences and Particularities

- Part III Home and Material Culture

- Selected Bibliography on Singles and Single Life, Western Europe, 1200–1900

- Index