Popular Music and Politics in Latin America

On 4 February 1992, a Venezuelan colonel called Hugo Chávez, together with other officers from a movement that had formed within the military, led an unsuccessful coup attempt against the country’s repressive and deeply unpopular government. Given time on national television that evening to call for the surrender of all remaining rebel military and civilian factions, Chávez assumed full responsibility for the failed attempt and announced that, ‘for now’, the movement’s objectives had not been met. Just over two years later, as he was released from prison on 26 March 1994 having served time for his role in the failed coup, Colonel Chávez was asked by a journalist if he had a message for the people of Venezuela. ‘Yes’, he announced, ‘Let them listen to Alí Primera’s songs!’. In December 1998, having formed a new political organisation and mounted a campaign rooted in these very songs, Hugo Chávez was elected president of Venezuela with 56 % of the vote, thus becoming the first head of state without links to the country’s establishment parties in over 40 years.

This book is about the dynamic ways in which music and politics can intertwine in Latin America; it explores how a popular national music legacy enabled Chávez to link his political movement at a profound level with pre-existing patterns of grassroots activism and local revolutionary thought. It is about the significance of Alí Primera’s music, and collective memories of that music, in Venezuelan political life, about how and why Chávez linked his political movement to Alí’s music, and about the ways in which this association affected the reception of Alí’s legacy in the Chávez era.

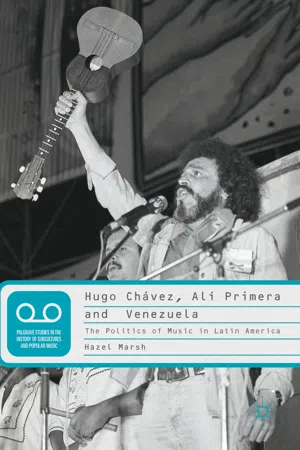

Alí Primera (1942–1985) was a

cantautor 1 who composed and performed from within the Latin American

Nueva Canción 2 (New Song) movement. He characterised his songs as

Canción Necesaria (Necessary Song),

3 and though he died some 14 years before the election of Chávez, Alí and his

Canción Necesaria were audible and visible in numerous forms in Venezuela in the Chávez period: in murals depicting a bearded man with Afro hair and a guitar or a

cuatro 4 in his hands; in lyrics painted on bridges and walls and quoted by Venezuelans in conversation and at meetings; in paintings, photographs and home-made figures placed in public and private spaces; in newspaper articles displayed in glass cases in the National Library in Caracas; at rallies and demonstrations in support of Chávez; at street stalls where bootleg CDs and DVDs were sold; on T-shirts and badges; at community radio stations; in students’ and workers’ organisations named for him; on the soundtrack of independent and state-sponsored films; on

’Aló Presidente, the weekly state television programme in which Hugo Chávez often broke into song and discussed Alí’s life and actions, and in political speeches, when Chávez regularly quoted Alí Primera’s lyrics and discussed their significance at length. Moreover, Alí’s

Canción Necesaria was officially endorsed and actively promoted by the state. In February 2005, on the twentieth anniversary of Alí Primera’s death, the Chávez government declared Alí’s songs to be part of the country’s cultural heritage and a ‘precursor of Bolivarianism’,

5 and the Ministry of Culture funded a number of documentaries and publications about Alí Primera and his music. For Venezuelans, and notably for Hugo Chávez himself, Alí Primera’s songs apparently mattered a great deal. Even when he addressed a shocked nation with the news of his cancer in June 2011, Chávez quoted lyrics from one of Alí Primera’s songs as he called for optimism:

I urge you to go forward together, climbing new summits, ‘for there are semerucos 6 over there on the hill and there’s a beautiful song to be sung,’ as the people’s singer, our dear Alí Primera, still tells us from his eternity. 7

Yet in spite of the surge in international academic and journalistic attention that Venezuela attracted after the election of Hugo Chávez in December 1998, the importance of Alí Primera’s songs for the Venezuelan public and for the Chávez government has been almost entirely overlooked outside the country. If Alí Primera has been commented on at all, he has tended to be referred to only in passing as a ‘folksinger’ or a ‘protest singer’ whose songs happened to be sung by Chavistas when they gathered to demonstrate their support for the government. Chávez’s frequent singing of these songs in speeches and on television seems to have been generally regarded as little more than an amusing or entertaining aside.

Music, however, is not mere entertainment; it embodies political values, memories and feelings, and it constitutes a realm within which political ideas and social identities are asserted, resisted, contested, negotiated and re-negotiated. In the twenty-first century, Alí Primera’s popular music legacy, and collectively remembered stories about his life and death, were in a unique position to serve specific and significant political functions both for the Chávez government and for the Venezuelan public. Venezuela in the Chávez era thus offers a distinctive case study of the complex and dynamic processes that render popular music constitutive of political thought and actions.

The Nueva Canción Movement in Latin America

Nueva Canción ‘constitutes perhaps the most widespread, organised, and deliberate challenge to corporate music industry manipulation by any artistic movement’ (Manuel

1988: 72). The late ethnomusicologist Jan Fairley (

2013: 120) has argued that the movement produced a body of popular music which remains ‘emblematic’ of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s; the songs which

Nueva Canción artists composed and performed became part of the social struggles they were tied to, yet these songs were not merely seen as

symbols of those struggles. According to Fairley, the very act of engaging with the songs constituted a form of social and political activism in and of itself:

To know the songs, to hear them, to personally distribute them by sending cassettes to others, to enthuse about them to friends, became a way of participating in the struggle for social change itself. Even though this might happen at a distance, it was an act of solidarity. (Fairley 2013: 122)

For Fairley (2013: 136), the ‘pervasive influence and longevity’ of Nueva Canción in the twenty-first century is in large part due to the fact that it was never created in ‘protest’ at all. Arguing that the term ‘protest’ obfuscated what was intended because it ‘offered a narrow meaning of songs before they were ever heard and led to false assumptions about hortatory or dogmatic content’, Nueva Canción musicians and audiences embraced a broad spectrum of political parties (Fairley 2013: 124–5). This rendered the movement ‘an integral expression of the complex life experience of a generation of different individuals who networked together’ (Fairley 2013: 136). It was the very breadth of experience and reality articulated in and through Nueva Canción that, according to Fairley, allowed the movement to become identified with a generation of young people looking for social, political and economic alternatives in Latin America in the 1960s–1980s. But brutal authoritarian regimes in the Southern Cone, combined with the Central American counterinsurgencies of the 1980s, appeared by the 1990s to have largely eradicated leftist movements in the region. Moreover, the fall of the Soviet Union and the subsequent isolation of Cuba together with the electoral demise of the Sandinistas in Nicaragua in 1990 ‘made any talk of a viable socialism appear hopelessly romantic’ at the end of the twentieth century (Webber and Carr 2013: 2). On the threshold of the twenty-first century, many assumed that the fragmentation of the political left rendered Nueva Canción and its associated values and ideas no longer relevant in Latin America (Fairley 2000: 369).

However, collective memories of Nueva Canción have played an important role in the so-called ‘pink tide’, a marked turn to the left in early twenty-first century Latin American politics, and the elections of several leftist governments have rendered the movement relevant in new ways. In Venezuela, Alí Primera and his legacy of Canción Necesaria provided Chávez with significant cultural resources with which to construct a legitimate political persona that immediately resonated with and appealed to broad sectors of society. This book does not aim to evaluate the successes or failures of the Chávez government and its policies, though I accept the evidence that in the Chávez period previously excluded sectors of the population benefitted both materially and in terms of access to social services and levels of political inclusion which had not been possible for them before (Hawkins et al. 2011; López Maya and Lander 2011). What I do argue is that while these benefits may account for continued electoral support, they do not in themselves fully explain the Chávez government’s ability to create what D. L. Raby (2006: 233) refers to as ‘a mutually reinforcing partnership’ through which many Venezuelans acquired a ‘collective identity and were constituted as a political subject’. The processes of transformation generated by the Chávez government relied not only on the redistribution of economic and material services and resources, but also on cultural politics and an engagement in work which, at a symbolic level, aimed to redefine the concepts of citizenship, democracy and the nation (Smilde 2011: 21).

Understanding the Appeal of Chavismo 8

Julia Buxton (2011: x) and Sujatha Fernandes (2010: 3–4) argue that the literature on Venezuela in the Chávez period is characterised by a polarisation between supporters and opponents of Hugo Chávez, with a tendency for both sides to adopt a ‘top down’ focus on ‘high politics’ which neglects to account for popular experiences of Bolivarianism. As Alejandro Velasco (2011) shows, scholars have tended to overlook the ways in which Bolivarianism grew out of and depended upon decades of political activism among underprivileged, marginalised and leftist intellectual sectors in Venezuela. Supporters have attributed Chávez’s popularity to ‘the fact that the government’s policies have benefitted the vast majority of Venezuelans’ (Wilpert 2013: 205–6). On the other hand, opponents of the Chávez government have predominantly viewed Chávez’s repeated electoral successes as a form of demagoguery or clientelism (Buxton 2011: xvii), or as the result of ‘a combination of demagoguery, populism, and the provision of reward and punishment’ (Wilpert 2013: 205–6). The Western press has...