eBook - ePub

Risk-Based Performance Management

Integrating Strategy and Risk Management

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Pulling together into a single framework the two separate disciplines of strategy management and risk management, thisbook provides a practical guide for organizations to shape and execute sustainable strategies withfull understanding ofhow much risk they are willing to accept in pursuit of strategic goals.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Continuous Turbulent Times: The Case for Risk-Based Performance Management

To future economic historians, the Credit Crunch might be the defining moment that separates the industrial age from the networked, digitized (or whatever name that they assign to it) era we moved into in the early part of the 21st century.

The early 21st-century revolution

A revolution is taking place in how organizations are structured, do work and go to market, and how they are regulated and scrutinized and secure sustainable competitive advantage. The competitive, regulatory and business landscape that senior managers will be expected to make sense of, manage and master in, say, 2020, will bear little, if any, resemblance to the organizational world that that they entered in 1990 – when most took their fledgling career steps as junior managers. Along the way they have witnessed (and largely successfully internalized into their thinking and working practices) unparalleled and breathtaking change: a technology-fuelled social, economic, political and competitive upheaval that has been simply staggering in its size, scope and impact.

As one quite humorous illustration, in the early 1990s one of the authors of this book interviewed a manager from a hi-tech organization that was a pioneer user of email. The poor manager complained that on some days he received almost 20 emails and that, as a result, managing his time was becoming increasingly difficult. We wish!

Fast forward to December 2010 and a tragic illustration of how this simple exchange of a few emails served as the foundation stone for unimaginable developments in digital technologies that would connect and redefine the world. A desperate, frustrated young man burnt himself to death in Tunisia because of his inability to find work and in despair at his treatment by the local authorities. What a few years earlier would have been noticed by just a few people (and quickly forgotten about by all but his family and friends) quickly served as a catalyst for the so-called Arab Spring, a series of protests and rebellions across the Middle East that brought down long-established governments and seriously destabilized others, and at the time of writing was still a long way from completion.

It was the global reach and influence of social media that led to this story being told to the world, and the galvanizing of others in Tunisia and quickly thereafter across the region to demand changes to their own circumstances. Who would have foreseen YouTube and Facebook back in 1990 and who would have foreseen the Arab Spring in early December 2010? And who can imagine what the world will look like in 2020, still less in 2030, as a result of further developments in digital technologies?

And switching our attention to the world of business, who can imagine the day-to-day challenges and realities that senior managers will grapple with in 2030? Most extrapolations that we make today will be far removed from reality. What we can predict with certainty is that senior managers will be leading organizations and making decisions in what can best be described as “continuous turbulent times”. We know this for a fact because they already are.

The Credit Crunch and ensuing recession, the Eurozone crisis and the US debt issue, as well as the Arab Spring, have proven beyond reasonable doubt the veracity of that statement. And such sudden and unexpected destabilizing events are likely little more than tasters of things to come as technological advances continue apace. To use the beginning of the cinema industry as a comparison: looking just a few decades ahead, the ICT capabilities then available for organizations and society generally might make today’s technology appear as primitive as the technology required to make single reel movies in the early decades of the 20th century appears to today’s cinematographers. The implications for individuals, society and economies are impossible to estimate with any reasonable expectation of accuracy.

New models for managing organizations: Introducing Risk-Based Performance Management

For business leaders, therefore, what are required are new models for managing organizations in this new economic landscape. Approaches are needed that enable the risks of doing business and prosecuting strategies in globalized and fully networked digital markets to be understood, managed and controlled, yet are simultaneously designed to exploit and gain competitive advantage from the myriad opportunities that this new world will offer and effectively manage the inherent risks in attempting to do so.

In this book we introduce Risk-Based Performance Management (RBPM) (Figure 1.1). RBPM represents a pioneering and powerful framework and methodology for enabling senior management teams to compete and survive in continuous turbulent times. RBPM embeds risk management into strategic and operational decision-making and positions risk appetite – the amount of risk that an organization is willing to take in pursuit of its strategic and operational objectives – as a central management and control tool. RBPM represents a practical results-focused methodology that enables executive teams to manage their organizations while operating within risk appetite.

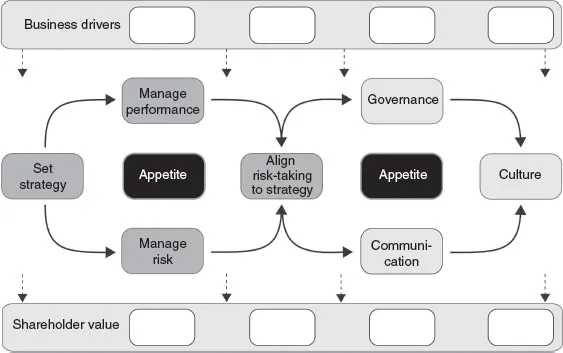

Figure 1.1 The RBPM framework

The RBPM framework describes a process from the capturing of the business drivers (the fundamental drivers of value of the particularly industry and organization) to the delivery of shareholder value.

Sequencing from the identification of the drivers of value to the delivery of shareholder value is through seven disciplines: Setting Strategy, Managing Performance, Managing Risk, Aligning Risk to Strategy, Governance, Culture and Communication; and an eighth (appetite) which serves as the glue that binds the others together into a unified strategy/risk management approach for these “continuous turbulent times”. We do not label appetite a discipline as its influence weaves through the seven identified disciplines.

The RBPM disciplines are described within two interrelated circles.

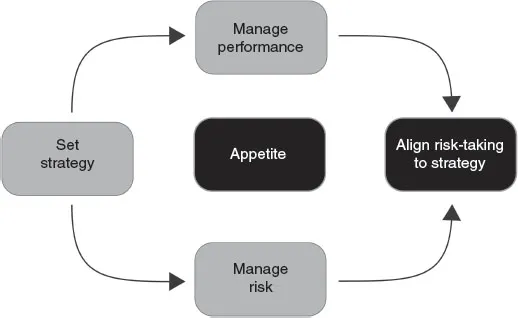

The circle to the left (Figure 1.2) is about defining and then executing strategy (by managing performance and managing risk). Appetite sits at the heart of both circles. Aligning risk-taking to strategy is a core discipline of this circle but also serves as the linkage to the circle to the right.

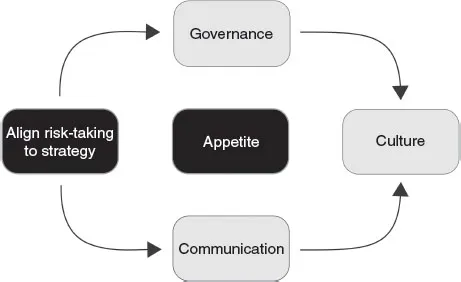

The circle to the right (Figure 1.3) considers the “softer” disciplines of RBPM: Governance, Culture and Communication. By “softer” we mean there is a lack of established mechanisms/processes for managing these disciplines, which is not the case for the other four disciplines. Moreover, although supposedly softer, they are no less important. Indeed, failure of governance and communications and, perhaps more importantly, culture is more likely than anything else to lead to the ignoring of risk appetite, the subsequent failure of risk management, and as a result, failure of the strategy. The RBPM framework delivers stronger governance at both the strategic (i.e., better tools and structures with which to manage the business) and cascaded levels through the RACI (responsible, accountable, consult, inform) model.

Figure 1.2 The circle to the left of the RBPM framework

Figure 1.3 The circle to the right of the RBPM framework

Chapter 2 is dedicated to fully describing the framework and methodology, Chapter 3 to explaining how it evolved from existing strategy and risk management frameworks, such as the Balanced Scorecard and the integrated Enterprise Risk Management Framework by the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations (COSO) of the Treadway Commission. The subsequent chapters explain how RBPM works in practice: describing how risk, and specifically risk appetite, is woven into the strategy formulation, execution and governance processes and how in applying the RBPM methodology, “softer areas” of culture and communication are powerful mechanisms to ensure that managers and staff are simultaneously strategy-focused and risk-aware, and so in the right shape to drive sustainable execution.

Learning from the past: The industrial revolution

But before we delve deeply into the disciplines of the RBPM approach, we should pause to reflect on how we got here. Doing so will provide insights into why strategy management is more important than it has ever been before and how the risks that organizations face today are also measurably more pressing – and therefore why we must rethink the central frameworks by which we manage organizations.

We will begin by stepping back to the late 18th century when, within the UK, the mechanization of parts of the textile industries along with other developments such as iron-making techniques and the introduction of canals and other transportation enhancements ushered in the industrial revolution. This catalysed the transformation from the 10,000-year-old agriculture-based economy toward one dominated by machine-based manufacturing.

The impact of Taylorism

However, the term “revolution” is something of a misnomer. What began in about 1775 was still unfolding in the early years of the 20th century, when a new work “revolutionized” approaches to working in industrial-age economies. The work was Fredrick W. Taylor’s 1911 monograph Principles of Scientific Management,1 which applied standard approaches to work methods along with detailed instructions for completing the required tasks and output-based incentives for workers.

Although Taylor’s approach to work proved enormously successful, as demonstrated by enthusiastic adopters such as the Ford Motor Company, the rigidity of the approach meant that workers were explicitly proscribed from contributing ideas on how to improve the performance of their processes, in particular or the organization more generally. Managers had brains, workers did not. As a result factory floor workers found their work monotonous and skill-reducing and they became emotionally dissociated from the organizations for which they toiled. There’s a compelling case for arguing that the shocking state of industrial relations in the West during the 1960s and 1970s can be laid at the door of Principles of Scientific Management, despite the undoubted benefits it brought to the efficiency of production. Taylor’s principles (or Taylorism) remained the standard approach to management and production for most (in the West at least) for the duration of the 20th century. But for the bulk of the time Taylor’s principles were deployed by organizations that operated in an economic landscape where competitors were few (even in industries significantly more mature than the manufacture of automobiles) and where customers were identifiable, local and generally loyal. Compare that environment with the one experienced by most organizations today.

Total quality management

In the latter part of the last century a new approach to running organizations emerged that had a profound effect on the management of manufacturing and other production processes, and later those that are more service related: Total Quality Management (TQM) and most notably the theories of the TQM “Gurus” Dr. Joseph M. Juran and Dr. W. Edwards Deming; although Deming, for one, never used the term “TQM”.

Both Juran and Deming made their names by helping to rebuild the industrial capabilities in the economically devastated post-Second World War Japan. Juran (who died in 2008, aged 104) was one of the first to think about the cost of poor quality. This was illustrated by his “Juran trilogy”, an approach to cross-functional management, which is composed of three managerial processes: quality planning, quality control and quality improvement. Without change, he claimed, there will be constant waste; during change there will be increased costs, but after the improvement, margins will be higher and the increased costs get recouped.

The theories of Deming (who himself lived to 93, dying in 1993) were encapsulated in his 14 points of management that, from one angle, went a long way to righting some of the more negative effects of Principles of Scientific Management.

Deming’s points differed sharply from Taylor’s principles in many ways. For starters, while Taylor put so much faith in the abilities of managers, Deming proclaimed that more than 90% of work problems were the fault of management, as did Juran. Whereas Taylor reduced the workers’ role to completing routine, standardized and often mind-numbingly boring tasks, Deming urged the removal of barriers that prevented workers from taking pride in their workmanship. Where Taylor urged strict silo-working, Deming called for the breaking down of barriers between departments. Even more challenging to the Taylor school, Deming called for the elimination of numerical quotas or work standards. “Quotas take into account only numbers, not quality or methods. They are usually a guarantee of inefficiency and high cost,” his points stated. Deming also argued against widespread usage of incentive compensation, and appraisals for that matter, on the grounds that there were too many variables in an individual’s performance to make any measurement statistically reliable.

In the next section we discuss the knowledge age. Note the prediction of Deming in one of his points, Encourage Education: “Institute a vigorous program of education, and encourage self-improvement for everyone. What an organization needs is not just good people; it needs people that are improving with education. Advances in competitive position will have their roots in knowledge.” In his own final years, Deming began to align his theories with the new challenges of the “knowledge age”. This was appropriate, as a central Deming teaching was focused on “profound knowledge”, which comprises four interrelated components: appreciation of a system; knowledge about variation; theory of knowledge; and knowledge about the psychology of change, all of which are still relevant today (and perhaps more so than ever).

Finally, the very first of Deming’s points resonates with some of the key challenges we will have in competing in the 21st century. This point is Constancy of Purpose: “Create constancy of purpose for continual improvement of products and service to society, allocating resources to provide for long range needs rather than only sh...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures, Tables and Boxes

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- 1. Continuous Turbulent Times: The Case for Risk-Based Performance Management

- 2. Risk-Based Performance Management: An Explanation of This New Strategic Paradigm

- 3. RBPM: Integrating Risk Frameworks and Standards with the Balanced Scorecard

- 4. Defining Strategy: The Question of Appetite

- 5. Understanding the Relationship between the Three Types of Indicators: KPIs, KRIs and KCIs

- 6. Managing Performance

- 7. Managing Risk

- 8. Aligning Risk-Taking to Strategy

- 9. Governance

- 10. Culture and Communication

- 11. The Enabling Role of Technology

- 12. Conclusion and Change Roadmap

- Notes

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Risk-Based Performance Management by A. Smart,J. Creelman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Strategy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.