eBook - ePub

The Culture of Translation in Early Modern England and France, 1500-1660

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Culture of Translation in Early Modern England and France, 1500-1660

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book explores modalities and cultural interventions of translation in the early modern period, focusing on the shared parameters of these two translation cultures. Translation emerges as a powerful tool for thinking about community and citizenship, literary tradition and the classical past, certitude and doubt, language and the imagination.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Culture of Translation in Early Modern England and France, 1500-1660 by T. Demtriou, R. Tomlinson, T. Demtriou,R. Tomlinson,Kenneth A. Loparo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Modern Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

From Cultural Translation to Cultures of Translation?

Early Modern Readers, Sellers and Patrons

Warren Boutcher

With the publication in 1975 of George Steiner’s seminal After Babel, ‘cultural translation’ became the key concept in translation studies. Steiner took the problem of translation out of the hands of the hard-core semioticians and transformational grammarians, and gave it to all students of the humanities and social sciences, even if it is debatable to what extent they have accepted the gift. He did this by defining culture itself as the transfer of meaning across time and space. At the time, the model of human cognition, communication and culture was essentially ‘linguistic-semantic’ and text-based. Cognition was a matter of decoding meanings from signs; communication was a matter of writing signs into texts; cultures were literary texts to be read. Steiner was therefore able to claim that the fundamental process at work in any act of translation, as in any act of human communication, was ‘the hermeneutic motion … the act of elicitation and appropriative transfer of meaning’.1

Since 1975, the ‘linguistic-semantic’ model used by Steiner has been much challenged on all fronts. There are now a number of different models in play, and they have begun to change translation studies.2 We have new, more pragmatic approaches to cognition and communication. These do not begin and end with the encoding and decoding of meanings in and from signs. They incorporate other aspects of daily interactive behaviour and other kinds of instinctive inference-making. When applied to translation, they produce new models of communicative relations between source writer, translator-as-reader, translator-as-rewriter and target reader. The process of communication becomes one in which readers (whether the translator, or the target reader) infer the most likely communicative intent on the basis of the various kinds of knowledge they bring with them. Meanwhile, our models of culture have moved ‘beyond text’ to incorporate visual and material artefacts, and the distinct kinds of communication and interaction they effect. In text studies, this means that far more attention is paid to the histories of books and manuscripts, and to the relations between print, script and orality. The focus on a relatively exclusive canon of literary translations has widened to include a broader range of texts.

These new models of cognition, communication and culture have not, however, displaced the old, text- and sign-based model of cultural transfer. In early modern translation studies, we are currently moving between old and new, looking for the best way to combine the two approaches. On the one hand, the task of painstakingly establishing the source and target texts, and undertaking a philologically informed comparison of the two, remains a crucial one. Otherwise, the translator’s interpretation, which may in turn indicate a politics of some kind, cannot be authoritatively revealed. Along with this goes the task of analysing changing theories of translation and interpretation, their ideology, their relationship to language learning, based on scrutiny of translators’ prefaces and treatises, and associated pedagogical literature.3

On the other hand, it no longer seems sufficient just to compare source and target texts and to ask questions about theories and ideologies of translation and pedagogy via prefaces and treatises. Larger patterns of mobility and migration, whether of books or of people, and broader networks of actors, in various roles, need to be considered. Translations in the early modern period are normally the outcome of the travels of individuals and of individual books to and from foreign countries, and this shapes the resulting texts in various ways.4 We now have more flexible models of the actions and agency relations that might be involved in the production and use of a translation – beyond just the actions of ‘domestication’ and ‘foreignization’, and the relations between the ‘interpreter’ and the ‘text’.5

Book history and cultural history have placed translations at the centre of a highly intricate nexus of authors, translators (including intermediary translators), paratext-writers, editors and correctors, censors, printers, booksellers, patrons and readers – so intricate, indeed, that it sometimes seems as if each translation has its own distinctive ‘culture’. Each translation, we might rather say, is the distinctive product of overlapping international, national and local cultures of translation, learning or pedagogy, and the book; each translation is a distinct act of communication carried out in a particular nexus of social relationships. To analyse a translation as an act of communication we need to go beyond purely literary and linguistic analysis, and beyond the usual sources.

In the second half of this chapter I shall consider three instances of early modern descriptions of such social nexuses, using non-standard sources, with a view to sketching the range of ways in which translations can constitute acts of communication. However, the quality of interpretative analysis will utlimately depend not on individual attempts to find and use new sources but on the collaborative scholarly provision of proper data and tools for the study of translation – by which I mean data and tools distinct from those provided for research into literary history conceived in terms of distinct national traditions, and comparisons between them. Such provision is underway – I give an example of how one such database can be used in the first half of the chapter – but it is still in its infancy.

One large problem is how little we know about what was actually translated and when, in print and manuscript, from which source texts or intermediary translations. And beyond that, how little we know about the transnational book trade, transnational book circulation, and the ownership of specific copies. There is a paucity of online tools designed specifically to facilitate the study of translations in their macro-contexts. This is largely because bibliographical projects have traditionally been designed to list national literatures, not the migrations of texts between them. The one traditional tool we do have is the period bibliography or list of translations from language A into language B, usually conceived within the context of a particular field of study which highlights the influence of one national literature upon another. But we are a long way from possessing comprehensive and informative databases of all the texts translated in the early modern period into and out of each of the European languages.

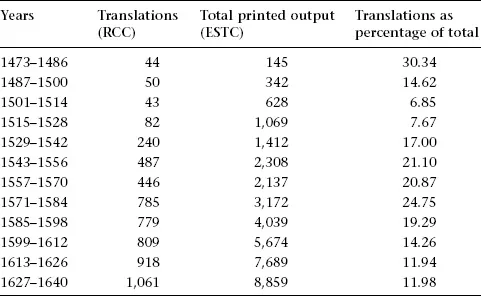

We currently have, indeed, only one such database: Brenda Hosington’s online resource containing a searchable, analytical and annotated list of all translations out of and into all languages printed in England, Scotland and Ireland, and of all translations out of all languages into English printed abroad, before 1641.6 The entries are modelled on the online ESTC but include new, independently verified information on intermediary translators, original language, target language, intermediary language, liminary materials and various other details regarding the translator and the translation (in general ‘Notes’). Even a basic search in this resource allows us to do something we have not been able to do before: statistically verify the growth of a culture of translation in the Tudor period, or, as Gordon Braden puts it, a ‘dramatic surge, unprecedented in its energy and scope, to bring foreign writings of all kinds into English’.7 Was there an Elizabethan renaissance in translation? Table 1.1 divides the period covered by both ESTC and RCC into 12 equal segments and shows the number of translations, total printed output and the number of translations as a percentage of total printed output. The latter element is shown graphically in Figure 1.1.

Table 1.1 Translations printed in England, Scotland and Ireland, and into English printed abroad, 1473–1640

Note: Data extracted on 24 February, 2013. As both the ESTC and RCC are continually revised, these figures are subject to future variations

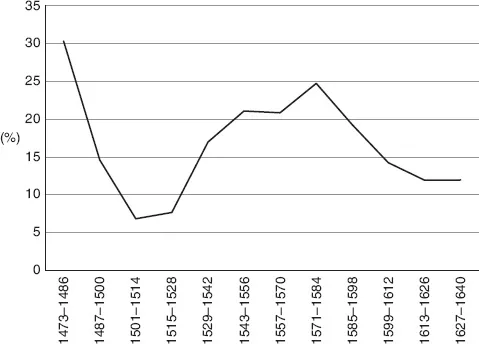

The data show that in their early years, English printers relied heavily on translated material to get production going. Thereafter, the proportion drops to a low level for three decades or so until the 1520s. There is then a steady rise, which does indeed peak in the mid-Elizabethan period, before a fall back to more moderate levels in the Jacobean and early Stuart periods.

Figure 1.1 Translations printed in England, Scotland and Ireland, and into English printed abroad, 1473–1640 as a percentage of total printed output

Until further research is carried out, we can only speculate what the key factor in this rise was. We should certainly not assume it was a surge in the production of classical and other literary texts in translation. The chronology would seem to point to the reciprocal relationship between the impact of the Reformation and the expansion of the book trade. Bible translation and a greater availability of foreign copies from the continent, especially the literature of the Reform and of religious controversy, perhaps combined with an increased capacity on the part of printshops and a greater willingness on the part of patrons to sponsor scholar-translators and booksellers to produce translated religious works. But an increased volume of translations of news pamphlets and other ephemera from the continent might equally have pushed the figures up in the 1570s and 1580s.8 It would be very useful to place the data in a comparative European context, to see if there are similar spikes in the proportion of translated materials produced in other European countries.

A tool that may be helpful in the future in achieving this aim is the new ‘Universal Short Title Catalogue’ (USTC) Project, based at the University of St. Andrews, directed by Andrew Pettegree.9 This is a searchable database of all books published in Europe before 1601 (to be extended in the next phase of development to 1650), with a note of located copies and, where possible, links to available digital editions. Currently, this database is not set up to provide comprehensive statistical information on translated texts and their sources, though future developments may change this. Within the project there is a distinction between internally created records and records assimilated from existing online catalogues. In the case of records created by the project team, which are mainly for Dutch, French, and German books, the names of translators are being listed. They also list, where known, the names of editors and secondary authors. The records assimilated into USTC from online national library catalogues, on the other hand, tend to be less helpful, as they are less likely to have included information about translators. Other important online databases such as Edit 16 (for Italy), VD 16-17, GLN 15-16 (for French-speaking cities of the Swiss Confederation), though extremely valuable, are likewise not set up for specialized research in the history of translation.

On the European scale, we also have the ‘Heritage of the Printed Book Database’ (HPB), formerly the ‘Hand Press Book Database’, a Union catalogue of European printing from the fifteenth century to the middle of the nineteenth century, hosted by the Consortium of European Research Libraries (CERL).10 Even since the launch of the USTC, this continues to be useful for the period after 1600. It allows searches by language and includes information about copies. But it is limited in being reliant on only around 19 or so online catalogues; these do not systematically record information about translated items, translators and intermediaries.

If we are interested in Europe as a whole, we must move forward as best we can, between old and new models of communication and translation, making generalizations based on case-studies and the scant data that are available. But we can also consider evidence on attitudes to translation and translation practices from outside the standard domains. In the remainder of this chapter, in an effort to broaden the range of sources used, I shall examine three texts about translation that are not drawn from translation prefaces or treatises. They offer us views from the study of the reader who buys and consumes translations, from the shop of the printer who produces them, and from the life of the patron who commissions them. My aim is to go beyond purely literary approaches to translation and to substantiate the claim that each translation is a distinct act of communication carried out in a particular nexus of social relationships, while also pointing to the diversity of possible nexuses in early modern cultures of translation.

The first example takes us to the study of Michel de Montaigne. Essais II.4 opens from the first (1580) edition with an award made not to the best translator in France, but to the best writer in France:

It seems to me that I am justified in awarding the palm, above all our writers in French, to Jacques Amyot...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on the Contributors

- Introduction

- 1 From Cultural Translation to Cultures of Translation? Early Modern Readers, Sellers and Patrons

- 2 Francis I’s Royal Readers: Translation and the Triangulation of Power in Early Renaissance France (1533–4)

- 3 Pure and Common Greek in Early Tudor England

- 4 From Commentary to Translation: Figurative Representations of the Text in the French Renaissance

- 5 Periphrōn Penelope and her Early Modern Translations

- 6 Richard Stanihurst’s Aeneis and the English of Ireland

- 7 Women’s Weapons: Country House Diplomacy in the Countess of Pembroke’s French Translations

- 8 ‘Peradventure’ in Florio’s Montaigne

- 9 Translating Scepticism and Transferring Knowledge in Montaigne’s House

- 10 Urquhart’s Inflationary Universe

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index