eBook - ePub

What's New about the "New" Immigration?

Traditions and Transformations in the United States since 1965

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

What's New about the "New" Immigration?

Traditions and Transformations in the United States since 1965

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Historians commonly point to the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act as the inception of a new chapter in the story of American immigration. This wide-ranging interdisciplinary volume brings together scholars from varied disciplines to consider what is genuinely new about this period.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access What's New about the "New" Immigration? by Marilyn Halter,Marilynn S. Johnson,Katheryn P. Viens,Conrad Edick Wright, Kenneth A. Loparo,Kenneth A. Loparo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Place

Chapter 1

The Metropolitan Diaspora

New Immigrants in Greater Boston

Marilynn S. Johnson

Announcing the recent release of the 2010 US Census results, the New York Times proclaimed, “Immigrants make paths to the suburbs, not cities.” The assertion was hardly new; similar headlines about immigrant suburbanization had accompanied earlier censuses dating back to the mid-1980s. This suburban diaspora has prompted an outpouring of speculation that new immigrants, like their European predecessors, have been abandoning the old urban centers for the safety and prosperity of the suburbs, or even bypassing the cities altogether.1

While the immigrant trek to the suburbs is indisputable, the implicit assumption that immigrants have been enjoying unprecedented upward mobility is misleading for several reasons. First, as metro areas have expanded, the landscapes of suburbia have grown accordingly. They include everything from old inner-ring industrial areas to semirural exurbia, from aging mill towns to rolling horse country. Moreover, much of the recent suburban growth has occurred in the South and West, where housing subdivisions have sprung up with lightning speed across orange groves, deserts, and foothills. Recent scholarship on immigrant suburbanization has focused disproportionately on such areas, some of which had little prior experience with immigration.2

We know less, however, about new suburban immigration to the older metropolitan areas of the Northeast. Here, an equally robust process of immigrant diffusion has been partially obscured by an earlier wave of European immigrant settlement in outlying towns and cities as well as confusion about what constitutes a suburb. Unlike newer Sunbelt areas, the older suburbs of New England and the Middle Atlantic were often popular destinations for European immigrants who fanned out of the large cities seeking employment in mills, quarries, construction, and maritime industries. Since the 1980s, new immigrants have gravitated to many of the same communities, sometimes attracted by linguistic and cultural connections to earlier ethnic groups. Ultimately, though, newcomers have encountered a profoundly different economic climate that for some has resulted in pervasive poverty and constrained mobility. Other newcomers, particularly Asians with more skills and education, have flourished and moved to some of the Northeast’s most affluent suburbs. Census definitions of these areas have changed, with some former suburbs now classified as cities, and some older industrial communities having lost their status as central cities. Given this diverse metropolitan landscape, new immigrants’ potential for social mobility has varied dramatically. This suggests that the conventional wisdom equating immigrants’ exodus from the city with upward mobility and assimilation needs qualification.

This essay attempts to explore these issues by examining immigrant suburbanization in Greater Boston. Following the lead of the new suburban history, it employs a broad definition of suburbia that encompasses the metropolitan area outside the city of Boston—communities that have varying class and racial/ethnic profiles.3 In an effort to document the diversity of migrant destinations and to see how and why new immigrants settled in these areas, it considers several types of suburbs: older industrial centers, affluent western suburbs, and the so-called one-step-up communities (more modest suburbs where immigrants have traditionally accessed upward social mobility). To understand the latter, the essay offers a historical excavation of three suburban Boston communities—Quincy, Framingham, and Malden—to explain how their economies and populations have changed over the years and how recent immigrants have built their communities on the foundations of the old. These transitions have not always been smooth. Since the 1970s, new immigrants have faced a dramatically different economy and opportunity structure, and resentments harbored by native-born residents have led to periodic outbreaks of anti-immigrant hostility and violence. Ultimately, however, immigrants have played important roles in diversifying and/or revitalizing these suburbs, even as the newcomers have struggled to claim a home for themselves.

* * *

As one of the nation’s oldest cities, Boston has a distinctive metropolitan history and form—one that is not well suited to traditional notions of city and suburb. Due to its early economic development and geographical constraints, the city decentralized quite early. Some of the oldest and largest industries in Massachusetts, such as textiles and shoes, were located outside of Boston to take advantage of rural labor and water power from local rivers. These sites ranged from more distant mill towns such as Lowell and Lawrence to those closer to Boston along the Charles, Sudbury, and Mystic rivers. Such industrial towns soon attracted immigrant workers, and in several of them, the Irish, French Canadians, Italians, and others developed distinct ethnic neighborhoods. Because Boston’s attempts to annex its neighboring communities ended rather early (essentially by the 1870s), the city’s land base remained small. New industry and populations thus began moving to these surrounding areas after 1890, filling in vacant parcels within the preexisting patchwork of older towns and manufacturing centers. The Boston metro area thus has a particularly long history of suburban development, one in which immigrants have played a vital part.4

After World War II, many of the smaller manufacturing centers experienced a precipitous decline, as did New England industry more generally. At the same time, spurred by federal support for higher education, home loans, and highway building, burgeoning middle-class suburbs grew up along and beyond what would become the Route 128 beltway west of the city. As middle-class whites (often second-generation Irish, Jews, and Italians) moved out of Boston and Cambridge, rising vacancy rates created housing opportunities for new immigrants arriving in the 1960s and 1970s. Beginning in the 1980s, however, Boston’s renaissance as a high-tech, medical, and financial services center attracted more affluent workers, who pushed rents and property values back upward. Many new immigrants thus had to look outside the city; by 1990, more of them were moving to the suburbs and nearby cities than were settling in Boston itself. In many cases, they moved into or near the smaller manufacturing centers that had long been home to immigrant workers. Those who could afford to do so moved to more prosperous suburbs near Boston and Cambridge or along Route 128.

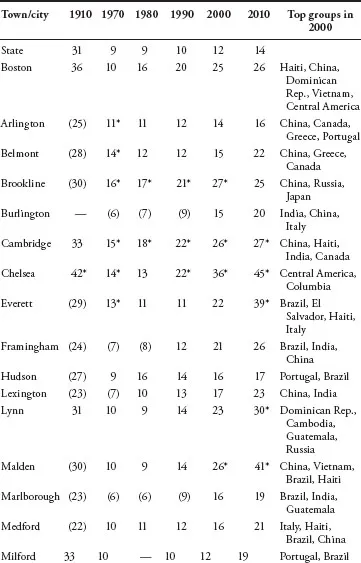

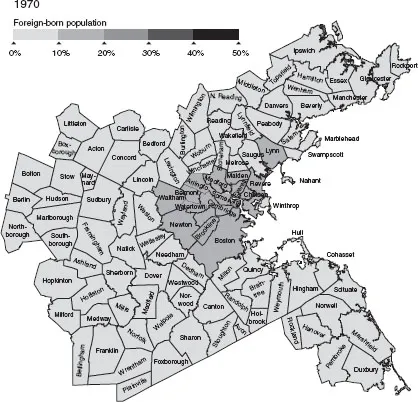

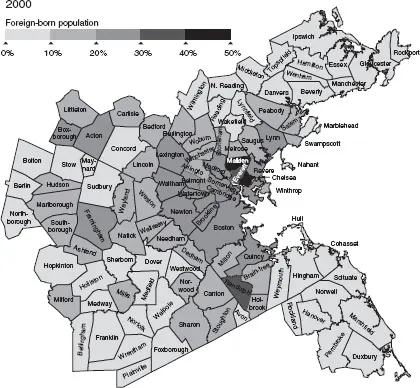

By 2010, 25 towns and small cities in the metro Boston area had foreign-born populations that were larger than the statewide average (see table 1.1 and maps 1.1 and 1.2). In recent years, both academics and the press have heralded the rise of immigrant suburbanization, noting that some migrants have been moving directly to the suburbs, bypassing the traditional urban immigrant enclaves. Although this has certainly been true in the Boston area, it does not mean that immigrant suburbanization is a uniform process or one that has simply reproduced the earlier experience of upwardly mobile European immigrants and their children. Exactly why this movement has occurred and what it means is a more complicated story.

Table 1.1 Percentage of foreign-born in selected Boston area suburbs (those with higher % of foreign-born than statewide average in 2010)

First, a significant proportion of new immigrants moving outside Boston have gravitated toward the Commonwealth’s older industrial communities—places such as Chelsea and Lynn. Built around burgeoning shoe and garment factories in the nineteenth century, these cities saw their industrial production and population peak in the 1920s, then undergo a protracted decline. The downturn in manufacturing in the decades following World War II was particularly devastating to these communities, bringing staggering (primarily white ethnic) population losses between 1940 and 1980—38 percent in Chelsea, 20 percent in Lynn.

Map 1.1 Foreign-born in metro Boston, 1970.

Despite the loss in employment, however, these communities all showed significant population growth after 1980, due largely to immigrants. During the 1980s and 1990s, thousands of foreign-born newcomers took up residence in neighborhoods such as West Lynn and Chelsea’s Downtown district. By 2010, the foreign-born population of Chelsea reached 45 percent, the highest in the state, while Lynn’s immigrant population reached 30 percent, the fourth highest. These rates equaled or exceeded those cities’ foreign-born population rates in 1910, showing that new immigrants were settling in many of the same places as their predecessors a hundred years earlier.

Unlike European immigrants who flocked to the mills, however, newcomers did not make jobs the decisive factor in choosing these smaller cities. While struggling local industries had sometimes recruited Puerto Rican workers in the 1960s and 1970s, newcomers arriving after 1980 were more likely to commute to service jobs in surrounding communities. Their own cities, meanwhile, suffered from continued job loss and unemployment as well as rising crime rates, failing schools, and ongoing fiscal crises. As such, they were not obvious choices for settlement. Lower housing costs, however, made them popular sites for federally subsidized refugee resettlement programs for Cubans, Russians, and Southeast Asians in the 1970s and 1980s. In many cases, these resettlement programs planted the seeds of the region’s growing Southeast Asian and Latino communities outside of Boston. Soon, increasing numbers of Dominican and Central American newcomers joined earlier Puerto Rican and Cuban residents, attracted by Spanish language and Caribbean cultural bonds as well as larger, lower-cost apartments. A 1990 study of Chelsea highlighted the city’s appeal for Latino families, noting that 87 percent of its Latino households had children under 18, compared to 73 percent of such households in Boston. The supply of relatively affordable housing in these old manufacturing centers, including thousands of aging or vacant triple-deckers, provided a strong draw for working-class Latino families.5

Map 1.2 Foreign-born in metro Boston, 2000.

These Massachusetts communities are part of a larger group of second-tier, industrial cities in the Northeast that have become increasingly important centers for poor and working-class immigrants. Thus, the exodus of many impoverished migrants from cities such as Boston and New York should not be confused with classic patterns of suburban migration and upward mobility. Although some observers have claimed that new migrants are simply following in the footsteps of the old, the larger restructuring of the metropolitan economy means that these new arrivals have few job prospect...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- Part I Place

- Part II Identity

- Part III Society

- List of Contributors

- Index