![]()

Chapter 1

Asia’s Consumer Spending Boom

Since the 1960s global consumer spending growth has been driven by the affluent societies in the US, Europe and Japan. However, the world economy is entering a new phase when the consumer spending of emerging Asia will become the most important driver for world consumer spending growth over the next two decades. This will be one of the key megatrends transforming the global economy, underpinned by strong GDP growth and rapid growth in the total number of middle class households in Asian developing countries, led by China.

Moderating long-term potential growth rates in the OECD countries has resulted in slower growth in consumer spending, notably in Japan where the falling population has been a major drag on household spending growth. Meanwhile the protracted effects of the global financial crisis in Europe have also resulted in weak consumer spending growth for close to a decade. Real retail spending growth in the European Union has been stagnant or declining in each year between 2008 and 2013, with very weak positive growth achieved in 2014.

In stark contrast to the performance of retail sales in Europe, Chinese retail sales growth has exceeded 10 per cent per year in real terms for every single year between 2005 and 2013. The rapid projected growth in the size of the consumer markets of China, India and ASEAN reflects rapid GDP growth, which is resulting in strong growth in per capita GDP levels as well as substantial growth in the total number of middle class households in Asian emerging markets.

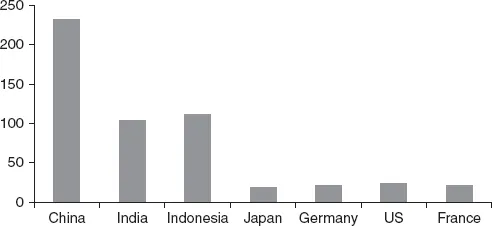

Figure 1.1 Household consumption growth, 2006–13

Note: Percentage change from 2006 to 2013.

Source: World Bank data.

The implications of sustained strong growth in consumer demand in Asian emerging markets is resulting in major shifts in the corporate strategies of multinationals, as they reposition their businesses towards the fast-growing markets of Asia. Multinationals have responded by increasing their foreign direct investment into Asian emerging markets, to expand their local presence and boost regional production to supply Asian markets.

The rapid growth of consumer demand in Asian emerging markets will also help to catalyse the growth of Asian companies in the manufacturing and service sectors, and will accelerate the rise of Asian emerging market multinationals. The tremendous expansion in the size of China’s domestic consumer market has already helped the development of many Chinese multinationals in a wide range of industry sectors, including telecommunications equipment manufacturing giant Huawei and Chinese e-commerce leader Alibaba Group.

China’s consumer market

Chinese per capita GDP when China’s great economic reforms began in 1978 was an estimated USD 180 per year. China was an extremely poor nation, with a large proportion of the population living in extreme poverty. Within one generation, the nation has experienced a far-reaching transformation in living standards, buoyed by sustained rapid growth averaging 10 per cent per year for three decades. By 2014, Chinese per capita GDP had exceeded USD 7,400 with China no longer a low (or even lower middle) income country but defined as an upper middle income country according to World Bank classifications.

China’s major coastal cities, notably Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzen, Tianjin and Guangzhou, have far higher per capita incomes than the Chinese national average. Beijing, which is China’s most affluent major city in terms of household incomes, had reached per capita GDP levels of an estimated USD 16,000 by 2014, around double the national average. The per capita GDP of Shanghai was comparable, at around USD 15,700 in 2014. These levels of per capita GDP are similar to those of the lower range of advanced economies. When compared to European per capita GDP levels, they are similar to those of Hungary or Malta, and well above those of Romania or Bulgaria.

The sheer weight of total Chinese GDP is also propelling China higher in terms of its ranking in world consumer markets. China has become the world’s second largest economy after the US, with its total GDP at around USD 10.5 trillion in 2015, compared to US GDP of 18 trillion. China’s GDP is now more than double that of Japan, which is estimated to be USD 4 trillion in 2015.

Figure 1.2 Size of consumer markets, household final consumption

Note: Trillion USD, nominal terms, 2013.

Source: World Bank data.

The rising affluence of Chinese households is becoming increasingly evident in key consumer industries in both manufacturing and services.

In the manufacturing sector, one of the most important indicators of the growing global importance of the Chinese consumer occurred in 2009, when the domestic sales of autos in China overtook the US for the first time. Chinese light vehicle sales reached 13.6 million in 2009, while US sales slumped sharply due to the impact of the global financial crisis, declining to 10.4 million light vehicles.

The Chinese auto industry has continued to grow rapidly since 2009, with total light vehicle sales in China reaching 23.5 million vehicles by 2014. By comparison, US light vehicle sales reached 16.5 million vehicles in 2014, a strong rebound of 58 per cent from the 2009 trough, but still considerably below the sales volume in China.

This rapid growth of Chinese auto sales has resulted in the Chinese auto manufacturing sector becoming the largest in the world, and, in turn, becoming a strategic focus for the world’s largest automakers. While factors such as traffic congestion and regulatory controls to limit the number of vehicles in major Chinese cities will become increasingly important constraints on the growth of Chinese auto sales in some of these large cities, rapidly rising household incomes will continue to support strong demand for autos across many of the smaller cities and rural regions of China, where traffic congestion is not yet a key constraint.

In the service industry, there are also clear examples of the rapid rise of Chinese consumer spending power. An important segment of the services industry in China that is growing rapidly is e-commerce, which is already estimated to be a USD 400 billion industry and has overtaken the US, becoming the largest e-commerce market in the world in 2013. The rapid growth of e-commerce in China has been driven by wide use of the internet and mobile phones, supported by the strong logistics industry presence in many Chinese cities.

One of the most dramatic signs of the rising affluence of Chinese households is the number of international tourism visits by Chinese abroad. In 2005, China was the seventh largest source market for international tourism in terms of total spending. By 2012, China had become the world’s largest source market for international tourism, with spending by Chinese tourists abroad reaching USD 102 billion, up around 40 per cent from 2011, according to the United Nations World Tourism Organization. (UN World Tourism Organization Press Release 13020, “China the New Number One Tourism Source Market in the World”, UNWTO, Madrid, 4 April 2013.) The UNWTO statistics indicate that the total number of international trips by Chinese tourists rose from 10 million in 2000 to 83 million by 2012.

Chinese international tourism visits have continued to grow rapidly since 2012, with the total number of international trips by Chinese tourists rising to 103 million by 2014, according to UNWTO statistics. Total spending by Chinese tourists abroad rose to USD 165 billion by 2014. This rapid growth reflects rising per capita incomes, supported by other factors such as the large number of new airports that have been built in China over the last decade and the rapid growth of low-cost carriers in the Asia-Pacific commercial air transportation industry, which has facilitated the boom in outbound tourism.

It is in Asia where the impact of these large statistical increases is most evident on the ground. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Thailand, where Chinese tourist arrivals reached 4.7 million in 2014, up 48 per cent on the previous year. Compared with 2011, when there were 1.7 million Chinese tourism visits to Thailand, the scale of the increase is staggering, with an additional 3 million tourist visits just 3 years later.

One of the rather bizarre catalysts for the rapid growth of Chinese tourism visits to Thailand was the release of a Chinese movie called Lost in Thailand in 2012, which was made as a low-budget comedy about Chinese tourists visiting Thailand but became a big Chinese language blockbuster, triggering a rush of Chinese tourists to Thailand that has continued to gather momentum.

I had noticed the significant increase in Chinese tourists in Thai hotels even during 2012 and 2013, but during a visit to Bangkok in 2015, the hotel I was staying in, located in the most central tourist area of Bangkok, was filled with Chinese tourists. The shopping malls and streets were also packed with Chinese visitors, many laden down with purchases from the department stores.

With China in the process of negotiating the construction of major new Thai rail links that could eventually connect with China’s high speed rail network, the rail linkages between southern China and Thailand could result in large new increases in Chinese tourism visits to Thailand using the future rail connectivity.

The Thai economy is heavily dependent on the tourism sector which accounts for around 8 per cent of GDP in terms of the direct impact effects of tourism output, and as much as 16 per cent of GDP after taking account of indirect multiplier effects. If large-scale increases in Chinese tourism inflows continue over the long term, this could have a very substantial positive impact on underlying economic growth in Thailand at a time when some of the other growth engines of the Thai economy have been sluggish.

While the impact effects of Chinese consumer spending in Thailand are particularly dramatic, there are similar effects evident in many other countries in the Asia-Pacific region in the last five years, as Chinese tourism visits have risen rapidly to many destinations.

Despite the geopolitical tensions between China and Japan over disputed sovereign territorial claims, which had even triggered widespread anti-Japanese riots in China in 2012, Chinese tourism visits to Japan boomed in 2014. Total Chinese tourism visitors to Japan in the 2014 calendar year reached 2.4 million, up 83 per cent from 2013, when political tensions had significantly dampened bilateral tourism flows.

When I visited Tokyo at the end of the Chinese New Year festival in 2015, I wanted to buy a small item from the duty-free shop at the airport in Tokyo. Normally Japan is a pretty efficient country and there aren’t long queues. However, I found myself confronted with a very long queue of people waiting to pay at the checkouts and wondered what was going on. I soon realized that all the people in the queue were Chinese tourists, since they were all clutching their passports in their hands, and each seemed to be carrying many identical boxes that they wanted to buy. While I waited in the long line, I looked at these boxes, assuming they were chocolates. However, I later realized that the boxes contained cosmetics, and it seemed that Japanese cosmetics were particularly sought after by the Chinese tourists. No doubt the significant depreciation of the yen since 2012 had also made Japan an increasingly popular destination for Chinese tourists.

Another sight that has become increasingly common in airports is to see Chinese travelers buying infant formula milk powder in large quantities before catching their flight back home. This has become a new trend for Chinese shoppers ever since the Chinese milk powder scandal in 2008, when melamine was found in some milk powder products.

The flood of mainland Chinese travellers buying milk powder in Hong Kong became problematic some years ago, as local Hong Kong shoppers were finding it increasingly difficult to buy supplies for themselves. The Hong Kong government reacted by creating new rules restricting the amount of milk powder that could be carried. I remember finding out about this while in Hong Kong airport, when I heard repeated announcements on the public address system warning passengers that there were significant penalties for carrying milk powder above the individual quota out of Hong Kong. In a world where customs officials usually target criminals who may be carrying narcotics or terrorists with deadly weapons, it seemed to be a bizarre situation where the Hong Kong officials were instead focusing their efforts on their own most wanted list, namely families carrying too much baby formula. One would have thought that the Hong Kong shops could have just air-freighted in large volumes of baby formula from Europe or New Zealand rather than going down this rather draconian route.

Chinese tourists spend a significant part of their travel budget on shopping, which accounts for around one-third of their total travel expenditure. This further increases the benefit to the local economy of the countries they are visiting. Some of the drivers for this very high level of spending on shopping are due to scale of the counterfeit industry in mainland China, as well as relatively high taxes on luxury goods. This makes it particularly attractive for Chinese tourists to buy luxury goods and other products such as cosmetics while visiting other countries. US and European cities are particularly popular for shopping expeditions to acquire high-value branded goods.

India’s consumer market

The Indian consumer plays a key role in the overall structure of the Indian economy, with private consumption expenditure having accounted for around 60 per cent of total GDP in the 2014–15 financial year. Taking into account government spending, which accounted for a further 11 per cent of GDP, the total share of consumption in GDP was 71 per cent of the overall economy.

Total private consumption in India in 2013 was around USD 1.1 trillion, compared to Chinese household consumption of USD 3.4 trillion and US household consumption of 11.5 trillion. India is already a very large consumer market by international standards when measured in terms of total consumer spending, comparable to household consumption of USD 1.3 trillion in Italy and USD 1.6 trillion in France in 2013.

A number of factors make India a key strategic market for global multinationals over the next decade and beyond.

Firstly, Indian potential GDP growth over the next decade is in the range of 7 to 8 per cent, and with accelerated large-scale infrastructure development, this rate could even reach 9 per cent. India has already grown at 8 to 9 per cent per year for a sustained period of time during the first term of the UPA government led by Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. Such high growth rates would, if realized, translate into strong growth in private consumption spending, driving the size of the Indian consumer market. In the 2013–14 and 2014–15 financial years, even though GDP growth momentum had moderated well below the 8 to 9 per cent range achieved a few years earlier, Indian private consumption grew at 6.2 per cent each year in real terms. This represents very strong growth when compared with consumer spending growth in OECD countries over the same time period, and continues to make India a very attractive market for global multinationals.

Secondly, Indian per capita GDP levels are still very low, with India still being towards the lower end of the lower middle income classification of the World Bank. Therefore sustained rapid economic growth would drive buoyant growth in consumer spending, as millions of households would enter the middle class each year. At such low levels of per capita GDP, rapid income growth would generate strong growth in demand for a wide range of consumer goods, including consumer electronics such as TVs, mobile phones, refrigerators, air-conditioners and kitchen appliances as well as fast-moving...