This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Michał Kalecki in the 21st Century

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Leading experts on Kalecki have contributed special essays on what economists in the 21st century have to learn from the theories of Kalecki. Authors include surviving students of Kalecki, such as Amit Bhaduri, Mario Nuti, Kazimierz Laski Jerzy Osiatynski, and Post-Keynesian economists such as Geoff Harcourt, Marc Lavoie, and Malcolm Sawyer.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Michał Kalecki in the 21st Century by J. Toporowski, L. Mamica, J. Toporowski,L. Mamica in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Economic Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Kalecki and Macroeconomics

1

The Failure of Economic Planning: The Role of the Fel’dman Model and Kalecki’s Critique

Peter Kriesler and G. C. Harcourt

The ‘purposive’ man is always trying to secure a spurious and delusive immortality for his actions by pushing his interest in them forward into time. He does not love his cat, but his cat’s kittens; nor, in truth, the kittens, but only the kittens’ kittens, and so on forward for ever to the end of catdom. For him jam is not jam unless it is a case of jam tomorrow and never jam today. Thus by pushing his jam always forward into the future, he strives to secure for his act of boiling it an immortality. (Keynes 1972, p. 330)

1.1 Introduction

In the 1920s, Soviet economists began to develop growth theory with the specific aim of facilitating the planning of their economy. Their work differed from that of most 20th-century economists because it was not aimed at academic economists but, rather, at politicians, bureaucrats and others involved in the machinery of planning. This meant that, although the work was often not as technical as the authors may have liked, it strongly related to the actual economy that they were attempting to model.

At the end of the 1920s, there was a debate about what are the appropriate goals for economic planning.1 The growth model developed by Fel’dman was regarded as the most important to emerge from that debate.2

Fel’dman’s initial training was as an electrical engineer, but he was involved with the Soviet Planning Agency, Gosplan, from 1923 to 1931. The growth model for which he is best known was part of a report to:

the Commission for the General Plan of the Gosplan of the USSR, concerning the question of the interrelationship of the rate of growth of reproduction of individual sectors of the economy among themselves and of the structure of the reproduction process as a whole. (Note of the editor of Planovoe khoziaistvo, Fel’dman 1928a, p. 174n.)

The Fel’dman model played an important role in influencing Soviet policy:

[It] expresses the foundations of the Soviet strategy for economic growth until the mid-1950s, based on priority for heavy industry and production goods; the same strategy was passively followed by the other socialist countries of Eastern Europe after the war. (Nove and Nuti 1972a, p. 13)

The priority given to heavy industry that emerged from the model played an important role in subsequent thinking about economic planning. The model has often been labelled as a ‘structural’ model because it was not just concerned with the absolute sizes of output and of investment, but is also with their composition. According to the model, the structure and composition of national output and, in particular, of investment will have as significant an influence on the rate of growth as their absolute values. The division of investment between capital goods for the consumer sector and for the capital goods producing sector is seen to be the key structural policy variable. Using this variable, Fel’dman developed an analysis of growth that foreshadowed the major western growth theories.3

This chapter examines the role of the Fel’dman model in determining the ‘method’ of economic planning, rather than with the environment in which it was developed or with the precise mechanics of the model per se. Rather, it is concerned with the influence of the model on subsequent Soviet planning and with the main criticisms of the model, particularly those by Michał Kalecki. The model has become synonymous with a way of thinking and of looking at the question of economic growth which manifested itself in the attitude stressing the absolute priority of industrialization and investment in heavy industrial capital/high capital intensity, at the expense of present consumption. Due to the role of the Fel’dman model in Soviet thinking and its strong association with Stalinism and Stalinist policies, providing a theoretical justification for heavy industrialization policy, it provides a good starting point for understanding some of the failures of economic planning in Eastern Europe, and for rethinking future roles for economic planning.

The next section of this chapter examines the Fel’dman model, outlining its salient features, first in a closed economy environment, and, in the following section, opening the model to trade. In the next section, some of the criticisms and extensions of the model are discussed. Problems relating to the Fel’dman model with respect to choice of technique are then examined. Kalecki’s critique and his concept of a ‘government decision function’ as a response to these problems are discussed subsequently.

1.2 The Fel’dman model

Underlying the Fel’dman model is an attempt to use the Marxian reproduction schemas to analyse long-run growth. As a result, there was some modification to the original formulation of the schemas, as Fel’dman abstracted from short-run crises in order to focus on the longer-run problems of capacity growth. In particular, concern with longer-term growth issues allowed him to abstract from shorter-run problems associated with realization of the surplus.4

In the Marxian reproduction model, Department 1 produces capital goods for the economy, and Department 2 produces consumption goods. Department 1 provides Department 2 with fixed and circulating capital. In the case of simple reproduction (no growth), this is done in order to maintain existing production levels, in other words, to cover replacement. In the case of expanded reproduction, additional capital needs to be provided in order to enable the economy to expand.

This gives rise to the idea of dividing the capital of sector A into two sections, of which one supplies sector B with the means of production required to sustain output at a given level, and the other supplies all industries in both sectors with additional capital to enable reproduction to expand. (Fel’dman 1928a, p. 176)

As a result, Fel’dman reformulated the model so that the output of each sector was determined solely by their final products. This meant that sector B not only included all consumption goods but also the capital used in producing those consumption goods.

The value of the output of sector B can include only the value of raw materials and that portion of the equipment and producers’ goods actually used up in the production of consumer goods. ... Thus the wear and tear of productive equipment in sector B must, by definition, be made good within that sector. ... [P]roduction must be divided into sector B, capable of maintaining consumption at a given level even with a cessation of the inflow of producers’ and consumers’ goods from sector A, which provides both sector B and itself with all the capital required for expansion of reproduction.

Thus, starting from Marx’s division, we have arrived at a new division which corresponds, however, to another division, the Marxian simple and expanded reproduction, the ‘production of income’ and ‘the production of capital’.

The only criterion for classifying production into the proposed sectors is whether it serves to increase capital ... or only to maintain consumption at a given level. (Fel’dman 1928a, p. 177–178; emphasis in original)

Sector B produces consumption goods for the economy and also what is needed to replace depreciation of both fixed and circulating capital (although Fel’dman later assumed away deprecation of fixed capital). This means that, in the case of simple reproduction, the economy would only need sector B, while the output of sector A is solely aimed at accumulation. So we are dealing with vertically integrated sectors.5

Sector A produces capital goods for itself and for any expansion in the consumption goods sector. Fel’dman assumed that, before they are installed, capital goods are malleable and can be installed in either sector. Once the capital is installed, however, it is no longer malleable and cannot, therefore, be shifted between sectors, that is:

A rolling mill cannot, so to speak, be constructed with the aid of a weaving loom, nor can a rolling pin be adapted for the production of cloth. (Fel’dman 1928a, p. 189)6

Fel’dman developed his model at various stages of abstraction. In expositing the analysis it is important to distinguish between analytically fundamental assumptions and those used to simplify the analysis. According to Fel’dman, the fundamental assumptions are constant returns to scale, given prices, the independence of production from consumption, and the absence of lags and any bottlenecks except in the production of capital.7

For simplicity, Fel’dman assumed that there was no depreciation of capital, that the supply of labour was infinitely elastic and that he was modelling a closed economy with no government sector.8 Although Fel’dman considers the implications of relaxing all these assumptions, except the last one, the economists who utilized the insights of the model, for various purposes, ignored the important possibilities of either labour shortages or international trade.

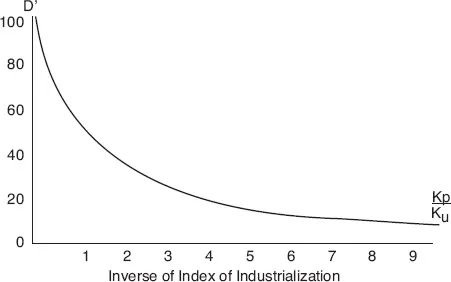

The essence of the model lies in the distinction between capital goods used to produce more capital goods and capital goods used in the consumption goods sector, which is embodied in the ratio:

where Ku = capital goods in the producer goods sector

Kp = capital goods in the consumer goods sector

Ik reflects the ‘index of industrialization’.

While Ik is given at any point of time, it will change over time as a result of a changing composition of investment, which was seen as the key policy variable affecting the long-run rate of growth of the economy. The allocation of the output of sector A between the two types of capital goods is the means by which policy influences the growth rate. The larger the proportion of sector A’s output which is ploughed back into sector A, the higher the subsequent growth rate of the economy will be. However, this results in less of sector A’s output being allocated to sector B, which reduces the economy’s ability to provide consumption goods in the near future. This means that, as a result of the assumption of the full employment of all resources, higher growth rates come at the expense of lower consumption levels.

The rate of increase in the growth-rate depended on the rate of increase in the proportionate size of the capital-goods sector, and hence on the proportionate allocation of current investment between the two sectors. (Dobb 1967 p. 110 emphasis in original)

In other words, the higher the proportion of the capital stock devoted to production of capital goods, the higher the growth rate of the economy. This is captured in the fundamental equation:

where D’ = rate of growth of net output

S = effectiveness of capital utilization which is the inverse of the capital/output ratio

D = net output

Du = output of capital goods sector, that is, accumulation

The rate of growth of output is determined by the effectiveness of the utilization of the capital stock and the proportion of total output devoted to the capital goods sector. The larger the ratio Du / D, the higher the growth rate will be.

Fel’dman argues that the ratio Ik, which is a reflection of Du / D, determines the possible rates of growth of the economy and illustrates this in the figure reproduced below.

In Figure 1.1 the curve also indicates how the rate of growth of income increases as a function of the industrialization of the country at every stage of development, for the ratio Ku/Kp is undoubtedly one of the primary indicators of the level of industrialization of the country, by virtue of the constantly increasing significance of industry in the contemporary economy. Thus an increase in the rate of growth of income demands considerable industrialization. ... heavy industry, machine building, electrification (Fel’dman 1928a, p. 194).

This illustrates the core proposition of the Fel’dman model, that to increase an economy’s rate of growth, there must be an increase in its level of industrialization. This requires a switch of resources away from the production of capital for consumption goods, in order to augment production of capital for the production of additional capital. As a result, there will be an immediate short-run fall in the production of consumption goods, due to the relative decline of the capital stock of that sector. However, since the economy is now growing at a higher rate of growth, eventually, consumption will attain a higher level than it otherwise would have. The trade-off between consumption and growth is, according to the model, only an issue in the short term. Of course, it is never clear for how long this short term will last. In the meantime, as the quote at the beginning of the paper indicates, ‘it is a case of jam tomorrow and never jam today’.

Figure 1.1 Growth rate of net output as a function of the degree of industrialization

Source: Fel’dman (1928a).

Contrary to the popular perception that the model advocates growth at the expense of consumption, it is an attempt to describe the conditions neces...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- Part I Kalecki and Macroeconomics

- Part II Kalecki and Crisis in the 21st Century

- Index