- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In this study two strands of inferentialism are brought together: the philosophical doctrine of Brandom, according to which meanings are generally inferential roles, and the logical doctrine prioritizing proof-theory over model theory and approaching meaning in logical, especially proof-theoretical terms.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Inferentialism: State of Play

1.1 What is meaning?

We may say, and we often do say, that what makes the difference between a word and a kind of sound that is not a word is that the former has meaning. Yet what does this mean? Thousands of books and articles have been written about the nature of meaning and I have no intention to survey them all here (needless to say, this would not be a humanly accomplishable task). For our present purposes it suffices to note that despite the immense efforts that have been put into these investigations no general agreement about the nature of meaning has yet been reached.1

The question regarding the nature of linguistic meaning is approached in multifarious ways. The first crossroad is opened up by the question of whether the phrasing ‘has meaning’ should be taken at face value, as expressing a relation between the word and some preexisting entity called meaning. Many philosophers have taken this for granted and have not seen it as disputable. A word, it is often claimed, stands for – or represents, or expresses – its meaning, and the reason it can do so is that we humans are simply symbol-mongerers: we have the peculiar ability to let one thing stand for another.2 However, the trouble is that it is very difficult to explain, in a non-mysterious way, how we do it and what the relation so established consists in. Is there some unanalyzable power of our minds that is capable of establishing symbols, and is the symbol bound to what it symbolizes by some mental fiber? It seems to me that it remains utterly mysterious not only what the nature of such mental mechanism would be, but especially how the mind could establish such public links as are essential for public language, and what these would consist in.3

It also seems to me that attempts at explaining the links directly in a naturalistic, especially causal way have not been very successful.4 Thus I am convinced that even if we disregard direct attacks on the coherence of such representational conceptions of meaning, due to Quine, Sellars, Davidson, and others,5 there are reasons to be skeptical about the prospects of fleshing out such a theory in a non-mysterious way.

These quick glosses, of course, are not to be taken as serious criticism, their purpose being only to remind the reader that no such approach has gained general acceptance as an explication of the concept of meaning, and that an effort to look elsewhere for another, more plausible explanation of meaningfulness is understandable. (Inferentialism, as presented in this book, is often thought to be a counterintuitive doctrine, so it warrants keeping in mind the problems plaguing rival conceptions of meaning to see that they face obstacles the circumvention of which might outweigh some amount of prima facie counterintuitiveness.)

But, of course, we need not take the meaning talk at face value; we could take it instead as metaphoric talk about some properties of words. Maybe what is characteristic of words – as contrasted with sounds that are not words – is not, or is not literally, that they stand for something, or express it, or represent it, but rather that they have some peculiar property. (The fact that we tend to talk about having a property as about being related to some reification of the property is not in itself mysterious, for it is something we do as a matter of course: we do not hesitate to speak about things having height, color, etc.6)

One of such explanations, the popularity of which has been on the increase over recent decades (especially thanks to the impact of the legacy of the later Wittgenstein), is that what characterizes a word is the way it is employed within our language games. According to this view, what we call meaning is, in fact, a reification of use. But the trouble is that all kinds of things around us have uses, and yet it seems that to be meaningful as a linguistic expression is something very different from being used, say, as a hammer. Could the difference consist merely in the complexity of the respective uses?

One alternative way of conceiving the difference is to distinguish between items like hammers, which merely have uses, and items like words, which have roles, where a role in the sense entertained here is something that is conferred on an item by rules. Here is where the underlying idea can be elucidated by comparing words with chess pieces (a comparison frequently used in this book): just as to make a piece of wood (or, for that matter, whatever substance) into a rook it is enough to subordinate it to the rules of chess, what makes a type of sound into an expression meaning thus and so are again certain rules – rules constitutive of our language games.

It seems to me that this opens up a non-mysterious way to explain meaning (chess does not seem to be a mystery!), and because such ways are in short supply, it is a view we might want to take seriously. Hence the idea is that what makes linguistic meaningfulness (aka having meaning) categorically different from other kinds of usefulnesses are the rules that govern the enterprise of language. According to this view, it is the fact that they are constituted by these rules that makes meanings into something special.7 Moreover, the fact that meanings presuppose a very specific kind of rules (including, be it only in the background, a framework of most basic rules, rules related to what we call logic) makes them into a sui generis, into entities of a kind that has nothing comparable in our world.

Inferentialism, the topic of this book, is a specific version of this view, according to which the most important kind of rules that constitute meanings are inferential rules. The term was coined by Robert Brandom (1994; 2000) as a label for his theory of language, which draws extensively on the earlier views of Wilfrid Sellars (1949; 1953; 1954). (Brandom has engaged the term especially to contrapose it to the common representationalism, i.e., the doctrine that meaningfulness consists in representing, i.e. in ‘standing for’.) However, the term is also naturally applicable (and is growing increasingly common) within the philosophy of logic,8 and indeed it is in the context of logic that we can most clearly see how inferential rules are supposed to give rise to meanings. Let us, therefore, now turn our attention to logic.

1.2 Inferentialism and logic

Probably the first expression of what we can, retrospectively, see as inferentialism is a passage from the pioneering work of modern logic, Frege’s Begriffsschrift:

The contents of two judgments can differ in two ways: first, it may be the way that the consequences which can be derived from the first judgment combined with certain others can always be derived also from the second judgment combined with the same others; secondly, this may not be the case. The two propositions ‘At Plataea, the Greeks defeated the Persians’ and ‘At Plataea, the Persians were defeated by the Greeks’ differ in the first way. Even if one can perceive the slight difference in sense, the agreement still predominates. Now I call the part of the contents which is the same in both, the conceptual content. (Frege, 1879, p. v)

The idea that the (logically relevant) content of a sentence is determined by what is inferable from it (together with various collateral premises) anticipates an important thread within modern logic, maintaining that the notion of content interesting from the viewpoint of logic derives from the concept of inference. This has led to the conclusion that the meaning or significance of logical constants is a matter of the inferential rules, or the rules of proof, that govern them.

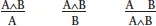

It would seem that inferentialism as a doctrine about the content of logical particles is quite plausible. Take, for instance, the conjunction sign; it seems that to pinpoint its meaning, it is enough to stipulate:

(The impression that these three rules do institute the usual meaning of ∧ is reinforced by the fact that they may be read as describing the usual truth table: the first two saying that A∧B is true only if A and B are, whereas the last one that it is true if A and B are.) This led Gentzen (1934; 1936) and his followers to study the inferential rules that are constitutive of the functioning (and hence the meaning) of logical constants. For each constant they introduced an introduction rule or rules (in our case of ∧ above, the last one) and an elimination rule or rules (above, the first two). Gentzen’s efforts were integrated into the stream of what is now called proof theory, which was initiated by David Hilbert – originally as a project to establish secure foundations for logic9 – and which has subsequently developed, in effect, into the investigation of the inferential structures of logical systems.10

The most popular objection to inferentialism in logic was presented by Prior (1960/1961). Prior argues that if we let inferential patterns constitute (the meaning of) logical constants, then nothing prohibits the constitution of a constant tonk in terms of the following pattern:

As the very presence of such a constant within a language obviously makes the language contradictory, Prior concluded that the idea that inferential patterns could furnish logical constants with real meanings must be an illusion.

Defenders of logical inferentialism (prominently Belnap, 1962) argue that Prior only showed that not every inferential pattern is able to confer meaning worth its name. This makes the inferentialist face the problem of distinguishing, in inferentialist terms, between those patterns that do, and those that do not, confer meaning (from Prior’s text it may seem that to draw the boundary we need some essentially representationalist or model-theoretic equipment, such as truth tables), but this is not fatal for inferentialism. Belnap did propose an inferentialist construal of the boundary: according to him it can be construed as the boundary between those patterns that are conservative over the base language and those that are not (i.e., those that do not, and those that do, institute new links among the sentences of the base language). Prior’s tonk, when added to a language that is not itself trivial, will obviously not be conservative in this sense for it institutes the inference A £ B for every A and B.11

The Priorian challenge has led many logicians to seek a ‘clean’ way of introducing logical constants proof-theoretically. Apart from Belnap’s response, this has opened the door to considerations concerning the normalizability of proofs (Prawitz, 1965) and the so-called requirement of harmony between their introduction and elimination rules (Dummett, 1991; Tennant, 1997). These notions amount to the requirement that an introduction rule and an elimination rule ‘cancel out’ in the sense that if you introduce a constant and then eliminate it, there is no gain.

Thus, if you use the introduction rule for conjunction and then use the elimination rule, you are no better off than in the beginning, for what you have proved is nothing more than what you already had:

The reason tonk comes to be disqualified by these considerations is that its elimination rule does not ‘fit’ its introduction rule in the required way: there is not the needed ‘harmony’ between them; and proofs containing them would violate normalizability. If you introduce it and eliminate it, there may be a nontrivial gain:

Prawitz, who has elaborated on the Gentzenian theory of natural deduction, was led, by his consideration of how to make rules constitutive of logical constants as ‘well-behaved’ as possible, to consider the relationship between proof theory and semantics. He and his followers then developed their ideas, introducing the overarching heading of proof-theoretic semantics.12

It is clear that the inferentialist construal of the meanings of logical constants presents their semantics more as a matter of a certain know-how than of a knowledge of something represented by them. This may help not only explain how logical constants (and hence logic) may have emerged,13 but also to align logic with the Wittgensteinian trend of seeing language more as a practical activity than as an abstract system of signs. This was stressed especially by Dummett (1993).14

1.3 Brandom’s inferentialism

Unlike Dummett, Brandom (1994; 2000) does not concentrate on logical constants; his inferentialism extends to the whole of language. As a pragmatist, Brandom concentrates on our linguistic practices, on our language games and on their place within our human coping with the world and with each other, but, unlike many postmodern followers of Wittgenstein, he is convinced that one of the games is ‘principal’, namely, the game of giving and asking for reasons. It is this game, according to him, that is the hallmark of what we are – thinking, concept-possessing, rational beings abiding to the force of better reason.

To make inferentialism into a doctrine applicable to the whole of language we must make sense...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Inferentialism: State of Play

- Part I Language, Meaning, and Norms

- Part II Logic, Inference, and Reasoning

- Postscript: Inferentialism on the Go

- Appendix: Proofs of Theorems

- Notes

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Inferentialism by J. Peregrin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.