This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

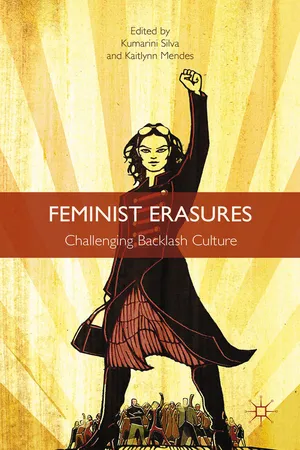

Feminist Erasures presents a collection of essays that examines the state of feminism in North America and Western Europe by focusing on multiple sites such as media, politics and activism. Through individual examples, the essays reveal the extent to which feminism has been made (in)visible and (ir)relevant in contemporary Western culture.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Feminist Erasures by K. Silva, K. Mendes, K. Silva,K. Mendes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Estudios de género. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Ciencias socialesSubtopic

Estudios de género1

Introduction: (In)visible and (Ir)relevant: Setting a Context

Kumarini Silva and Kaitlynn Mendes

Who we are and why we care

We are feminist scholars and educators who live on opposite ends of the ‘pond.’ We are also, when not writing and teaching, mothers, partners, daughters, sisters, and friends to a myriad of people in our lives. Our own experiences as women who work, in a conventional sense, and then work as gendered beings provide a foundation for our approach to this book. We fully recognize the burdens our gender places on us; at the same time we acknowledge the many opportunities that feminism has given us. The historical struggles of the feminist movement have given us the tools, the means, the legislature, and the social context to thrive in the ways that are important to us in our personal and professional lives. In keeping with this, the diversity of this book reflects the many spaces that women occupy and perform gender, and the ways in which these performances translate to cultural norms and conventions about being female.

Over the last half-decade we’ve collaborated on various projects, and spent a great deal of time talking about feminism and feminist cultural politics with each other, as well as with broader audiences through our own individual research and projects. While our discussions have always been about the relationship between feminism, culture, and politics, the genesis for this particular project comes with the intersection of several political and popular events happening over the last few years in the US and UK where we live and work. While the following events might seem disparate, they have created the cultural context from which these essays emerge: from the discourses surrounding the vice-presidential candidacy of Sarah Palin in the US in 2008; to political discussions of rape as either ‘legitimate’ (in the US)1 or ‘bad sexual etiquette’ (in the UK),2 to controversies surrounding gay marriage in the US, to the rise of ‘mommy porn,’ in both literary and mediated contexts, these seemingly disparate conditions fuel a particular and often times contradictory narrative about women in contemporary culture. In addition, we have chosen to focus on North America and Western Europe, because we believe that it is important to interrogate the spaces we occupy in order to understand how our own lives are shaped by patriarchy and feminist interventions. Looking at the ‘Other’ as experiencing marginality, while ignoring your own, creates a false sense of accomplishment, while stifling progress and change. If we pay attention to our own context, we will recognize that in our everyday lives, misogynistic imagery and discourses about women are used over and over again as exemplars of women’s control over their own bodies, their sexuality, and their lives. And the systemic (in that, this contradictory message is present in all aspects of society from mediated images to political discourse) distribution of these contradictory images results in a form of apathy about feminism and women’s rights as either irrelevant or ‘too much work.’ Essentially, ‘what to believe?’ and ‘whom to believe?’ inevitably results in ‘so what?’ and ‘who cares?’

What is at stake: So what? and Who cares?

If the broader context of feminism and its discontents are grounded in the fact that most young women (and men) believe that feminism is a choice, that can be discarded or appropriated as necessary, it begs the question, what is at stake? What do we have to lose through the abandonment of feminism and its genealogical history and contemporary manifestations? For us, what is at stake is the erasure of feminism as a completed project before its work is done. That the current circulation of postfeminist discourses, in both popular and political culture, creates a sense of ‘after’ that we, among other feminist scholars (see Douglas 2010; Negra 2009; Tasker & Negra 2007), feel is inaccurate. The apathetic approach to understanding the importance of feminism and its genealogical history makes us immune to the systemic backlash against women that has become part of everyday culture. Here, let us take a moment to explain what we mean by an apathetic approach to feminism: for us, it’s a condition where the progress made by feminists and women’s rights movements, on a global level, are presented as a fait accompli and any ongoing activism or commitment to feminism is seen as outmoded and unnecessary. It is the simple belief that ‘women have arrived’ in spite of significant evidence to the contrary. This contrary evidence can be seen in the continued use of sexualized imagery and violence against women to sell products, in the legislative practices that are routinely enacted which negatively affect women’s health benefits, the continued double-burden that is placed on women who work both within and outside the home, the continued debates around welfare mothers and the general judgment placed on single mothers, just to name a few. In spite of these realities, women are continuously and relentlessly encouraged to believe that there is nothing more to be done. That women’s liberation has arrived and triumphed. But, as the chapters in this anthology suggest, such a declaration is not only inaccurate, it can also have significant drawbacks for continued activism and engagement with issues of gender, class, race, and sexuality that are much needed in contemporary culture.

As Michel Foucault reminds us, none of these entities/discourses about social structure, power, and agency exists independently. Foucault writes that ‘We must make allowances for the complex and unstable process whereby a discourse can be both an instrument and an effect of power, but also a hindrance, a stumbling point of resistance and a starting point for an opposing strategy. Discourse transmits and produces power; it reinforces it, but also undermines and exposes it, renders it fragile and makes it possible to thwart’ (1998, pp. 100–1). In keeping with this, we approach various cultural and political events, materialities, and texts as a collection of discourses that reinforce each other to both stabilize and destabilize power structures within North American and European contexts.

We are especially cognizant that these discourses and power structures disproportionately affect women, and create a culture of implicit (and explicit) misogyny and disempowerment that becomes naturalized, systemic, and institutionalized. For example, neoconservative politics that limit women’s rights and a mediated culture that commodifies and distributes images of misogyny as empowerment are interconnected in that they rewrite the new politics of feminism. This particular politic tells us that feminism is, in fact, irrelevant. As Angela McRobbie writes, ‘this new kind of sophisticated anti-feminism has become a reoccurring feature across the landscape of both popular and political culture. It upholds the principles of gender equality, while denigrating the figure of the feminist’ (2009, p. 179). This anti-feminist feminism is echoed in our classrooms, where we often hear from students that while they believe in ‘equality,’ feminism is a ‘choice,’ and that the word feminist carries too much ‘baggage.’ The contradictions between equality and choice, and the inherent privilege in enjoying the systemic and structural benefits that the feminist movement has brought about while discarding the politics of feminism, are lost in the midst of the cacophony that is contemporary mediated culture. And political discourse joins the popular in appropriating the language of feminist liberation and empowerment in the construction of an essentializing feminism that re-marginalizes and domesticates women. That is, in fact, the definition of backlash culture: a negative reaction to the possibility of progress and/or change.

Backlash and the culture of ‘choice’

On 16 January 2014 US talk show host Elizabeth Hasselbeck asked Nick Adams, author of The American Boomerang (2013) – a book that looks at the relationship between the decline of American exceptionalism and the (supposed) decline of masculinity – whether such a decline was ‘in direct relation to feminism on the rise?,’ continuing with ‘Is it a result just sort of society seeing men that are not as masculine and men that are as masculine being kind of demonized?’ Adams responded by telling her that she ‘hit the nail on the head.’ In the course of that interview Adams and Hasselbeck concluded that the rise of feminism, and the apparently (completely unfounded) co-relational decline of masculinity, resulted in a threat to national security. While this conversation was decried by many in various venues, the very existence of Adams’s book and Hasselbeck’s questions indicates the kind of misguided notions of feminism that circulate in contemporary culture. But such notions are not without precedence. In the 1970s, British columnist Christopher Ward noted satirically that:

I hadn’t realized just how much bad news we men have suffered until I came across this Liberated Woman’s Appointment Calendar and Survival Handbook, which is rapidly becoming the pocket book of every bra-burning American lady. Every day this diary records the anniversary of some past female victory, which we men have been suffering for ever since. I mention here some of the more prominent landmarks in the history of Women’s Liberation so that, while women celebrate them, we men can treat them as days of mourning of our formerly great sex. (Ward 1970, p. 7)

And in the early part of the new millennium, the British writer Deborah Orr noted that, ‘Feminism is blamed, completely erroneously, for everything – spiralling property prices (working couples), unemployment (women stealing men’s jobs), teenage delinquency (feminists driving men to abandon their sons), reality television (the “feminization” of the culture) and increasing sexual violence (now that women don’t defer to them, men have suffered a violent “identity crisis”)’ (2003, p. 15). More recently, speaking to this ongoing condition of blame on and backlash against feminism, McRobbie (2009) writes:

Elements of feminism have been taken into account, and have absolutely been incorporated into political and institutional life. Drawing on a vocabulary that includes words like ‘empowerment’ and ‘choice,’ these elements are then converted into a much more individualistic discourse, and they are deployed in this new guise, particularly in media and popular culture, but also by agents of the state, as a kind of substitute for feminism. (p. 1)

McRobbie goes on to call this ‘faux feminism.’ And within faux feminism, ‘choice’ is the linchpin that promotes a false sense of empowerment for women in contemporary culture. This is perhaps most easily identifiable in advertising marketed to young female consumers, who are encouraged to make ‘empowering choices’ through consumption. Take, for example, the ‘Rule the Air’ advertising campaign by the largest mobile network operator in the US, Verizon.3 Debuting in 2010, the company released a series of ads targeting the much coveted youth demographic. In an advertisement titled (rather ironically) ‘prejudice,’ a series of young women, from different ethnic backgrounds, relay the following message to the audience:

Air has no prejudice, it does not carry the opinions of a man faster than those of a woman, it does not filter out an idea, because I’m 16 and not 30, Air is unaware if I’m black or white, and wouldn’t care if it knew. So it stands to reason, my ideas will be powerful, if they are wise, infectious, if they are worthy, and if my thoughts have flawless delivery, I can lead the army that will follow. Rule the air. Verizon.

Here, a series of random thoughts, none of which factually, or even theoretically, make a coherent argument, are strung together to encourage a feeling of accomplishment and success by buying Verizon products. We are not expected to question the notion that ideas generally (at least, in theory) do need to be ‘wise’ to be powerful or infectious, or that the worth of ideas is measured by their capacity to gain power in and within a patriarchal society, where women are routinely and systematically marginalized. Such critiques are irrelevant as the advertisement winds down by reiterating the notion of perfection for these young women, because only ‘flawless delivery’ will allow leadership – and, of course, it ends with consumption as power: ‘Rule the air. Verizon.’ Essentially, as Susan Douglas (2010) writes: ‘What the media have been giving us, then, are little more than fantasies of power. They assure girls and women, repeatedly, that women’s liberation is a fait accompli and that we are stronger, more successful, more sexually in control, more fearless and more held in awe than we actually are’ (p. 5).

It is this form of empty empowerment located within consumerist choice that is mirrored in recent political discourse. In both North America and Western Europe, feminism, women’s rights, and politics have become recent news fodder.4 For example, the 2008 US election was a watershed moment, not just in terms of racial politics, but also gender politics, with Hillary Clinton as a possible presidential candidate, and Sarah Palin as a vice-presidential candidate. The latter, then governor of Alaska, was an unknown political entity, selected to become the vice president to presidential candidate John McCain. During the campaign, Palin managed to parlay her Alaskan roots and religious beliefs into a new form of ‘choice feminism,’ rooted in conservative, pro-life values, that made her extremely popular among religiously conservative, anti-choice advocates. Her supporters read her commitment to a large family, including a special needs child, as a symbol of a ‘new kind of feminism,’ one which was grounded in anti-abortion, right-wing conservatism and ‘family values.’5 Palin documented this new feminism in her memoir titled: America by Heart (2010), where she states that ‘The new feminism is telling women they are capable and strong. And if keeping a child isn’t possible, adoption is a beautiful choice. It’s about empowering women to make real choices, not forcing them to accept false ones’ (p. 153). She goes on to explain that ‘left-wing feminists are out of touch with the real America,’ and that ‘Judging by the emergence of the mama grizzlies, it’s becoming more acceptable to call yourself a pro-career, pro-family, pro-motherhood, and pro-life feminist’ (p. 137). While we do not critique Palin’s commitment to her family and acknowledge that a special needs child presents unique challenges to childrearing, her glib and uncritical celebration of women’s double-burden, economic and political marginality, and the right to no-choice, showcases what Susan Douglas calls ‘pit bull feminism.’

According to Douglas, with pit bull feminism, ‘you have the appearance of feminism – alleged superwoman, top executive, and mother of five – with a repudiation of everything feminism has fought for’ (2010, p. 271). Indeed, Palin’s kind of political pit bull feminism and its companion in popular culture, faux feminism, essentially positions feminism as a generational, economic, social or political difference, where discussions around misogyny, double-burden, and rights seem outdated and unnecessary. Here, a more nuanced discussion is whittled down to ‘choice’ without an accompanying discussion about the inherent privileges of having and making choices. This false sense of choice-as-empowerment is also closely tied to and exasperated by the ways in which we have married choice to democracy, especially within the capitalist democracies of North America and Western Europe. Because democracy, within hyper-consumerist societies, is tied largely to consumer freedom, that choice of consumption stands in for democratic rights and privileges. This notion of choice is seen as unique to Western democracies and is used as a way to separate the political, social, and consumer cultures of the West from the non-West. For example, there is a common assumption that the West (made up largely of the US and other Western European nations) is more progressive and politically democratic than ‘non-Western’ spaces. This, in spite of the fact that the US is the only industrialized nation to vote against the ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). Because of a combination of historical and contemporary trends – including colonialism, balkanization, and globalization – too long to document here, there is a common notion that the West defined women’s rights and therefore practice them the best. Such a mentali...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Notes on Contributors

- List of Abbreviations

- 1 Introduction: (In)visible and (Ir)relevant: Setting a Context: Kumarini Silva and Kaitlynn Mendes

- Part I Teaching Feminism

- Part II Feminism in Popular Culture

- Part III Becoming Mother

- Part IV Feminism/Activism

- Index