This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Time, Domesticity and Print Culture in Nineteenth-Century Britain

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This innovative study shows that nineteenth-century texts gave domesticity not just a spatial but also a temporal dimension. Novels by Dickens and Gaskell, as well as periodicals, cookery books and albums, all showed domesticity as a process. Damkjær argues that texts' material form had a profound influence on their representation of domestic time.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Time, Domesticity and Print Culture in Nineteenth-Century Britain by M. Damkjær in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literatura & Crítica literaria europea. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

LiteraturaSubtopic

Crítica literaria europea1

Repetition: Making Domestic Time in Bleak House and the ‘Bleak House Advertiser’

In the distribution of [the boiled pork and greens], as in every other household duty, Mrs Bagnet develops an exact system; sitting with every dish before her; allotting to every portion of pork its own portion of pot-liquor, greens, potatoes, and even mustard; and serving it out complete.

Charles Dickens, Bleak House (November 1852)1

Boiled beef and greens constitute the day’s variety on the former repast of boiled pork and greens; and Mrs Bagnet serves out the meal in the same way, and seasons it with the best of temper.

Dickens, Bleak House (January 1853)2

If domestic time has a basic structure, that structure is repetition; its backbone is formed out of routines. Dinner, for instance, must be prepared every day; yet novels, for obvious reasons, do not tend to give details of every single meal. Charles Dickens, however, is unusual in his elaboration of banal everydayness, and Bleak House (1852–3) is a novel with a peculiar stake in narrating what is normally invisible. The narrative uses repetition as a structural element and as a trope in itself. Mrs Bagnet’s two family dinners – pork and greens followed by beef and greens – occur two monthly numbers apart (November 1852 and January 1853). The repetition serves three purposes. First, such repetition is part of Dickens’s endeavour to bring all characters before the reader’s eyes at regular intervals during the 19-month-long run. Secondly, such repetition supplies Dickens’s well-known method of characterization, one that tends to associate characters with idiosyncratic actions and particular speech patterns. And thirdly, on a formal level such repeated actions are the mainstay that produces virtuous domesticity – the primary hope for the nation as a whole.

In Bleak House, domestic time is located in repeated actions: the codified ringing of bells for meals, the rhythms of cooking, account-keeping and supervision, and the small tasks which characters are engaged in when the narrative lingers on them. The novel is shot through with references to Esther Summerson’s jingling bunch of keys, making her domestic management a base beat of recurrent significance. As a counter-rhythm, the ominous step on the Chesney Wold terrace is a recurring sign of the decline of aristocratic power in the face of new, active bourgeois self-fashioning. Time is measured out in Bleak House. The project of the novel is the making of the middle-class home, and the narrative follows characters who are deliberately and painstakingly filling up time. Whereas Agnes Wakefield in David Copperfield (1849–50) conducted her home silently and unobtrusively – linked, in the narrator’s mind, to an eternalized ideal of domestic womanhood, silently pointing towards heaven – domestic time in Bleak House is obtrusive in its repetitive insistence. Mrs Bagnet is militantly exact in her management. Similarly, Esther’s keys, which act as her self-disciplining subconscious, also link her to the rhythms of daily life. Partly, this insistence on routine tasks is a function of the novel’s aim: to narratively construct the middle-class home as a bourgeois power centre. But it is also partly owing to a historical tendency to establish the details of everyday life, and to restate them more emphatically, which came to a head in the 1850s. The net movement was towards length and detail. Household manuals projected confidence in their ability to be all-encompassing. Beeton’s Book of Household Management was only one of a long line of manuals intended to describe every aspect of everyday life and solve every query. In a spirit of class consolidation, fiction as well as non-fiction took part in this drive to be specific, exhaustive, and authoritative. In Bleak House, Dickens uses the topos of repetition to suggest an easily reproduced household, one running on a logical plan. In the process, repetition is pushed as far as realism will allow it. Characters duplicate their own actions, clearly expecting similar results. Henri Lefebvre has cautioned that repetitive rhythm inevitably incorporates change over time: ‘there is no identical absolute repetition, indefinitely […] [T]here is always something new and unforeseen that introduces itself into the repetitive: difference.’3 Dickens’s characters in Bleak House, especially Esther Summerson and John Jarndyce, work actively to deny dynamic change, as we shall see.

Repetitive activity, such as humdrum housework, is problematic in narrative because it can lead to monotony; when domesticity is described as repetitive it takes on an association with pointlessness, making it seem as if household tasks are never finished and domestic time never goes anywhere. Dickens has often been identified as a writer who traps his female characters in profoundly undynamic loops, denying them growth and change. In an attempt to give this idea a positive spin (and based on a misreading of Julia Kristeva’s ‘Women’s Time’ which ignores Kristeva’s warning against gender essentialism), Elizabeth A. Campbell has argued that:

rather than envisioning time as history, moving in a linear fashion (the temporality traditionally associated with men), Dickens’s narratives [of women] give priority to time’s cyclicality, to the representation of time as a space that emphasizes at once repetition and eternal return.4

As this chapter will show, I profoundly disagree with this statement. The first part of my analysis may in fact seem to confirm that Bleak House aligns ‘repetition’ with ‘cyclicality’ and ‘eternal return’, as Campbell suggests. But as the repetitions accumulate, and as Dickens elaborates domestic tasks more and more (to the point of absurdity), these loops begin to look strange. Repetition and cyclicality are not, in fact, synonymous: no repetition can ever be perfect, and so repeated actions or events always carry a seed of change with them. A household manual may require users to repeat their actions every time a recipe is revisited, but the dish will never work out the same way twice. Writers of household manuals must abandon any idea of complete reproductivity and aim for a universal discourse of active, sometimes inventive, performance.

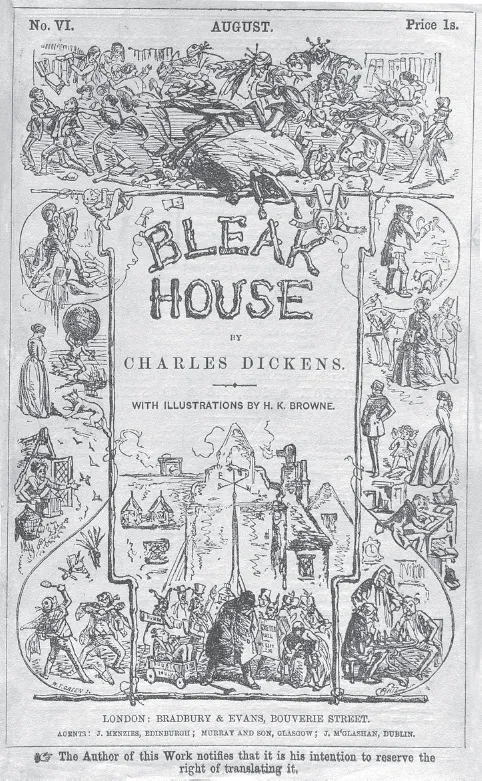

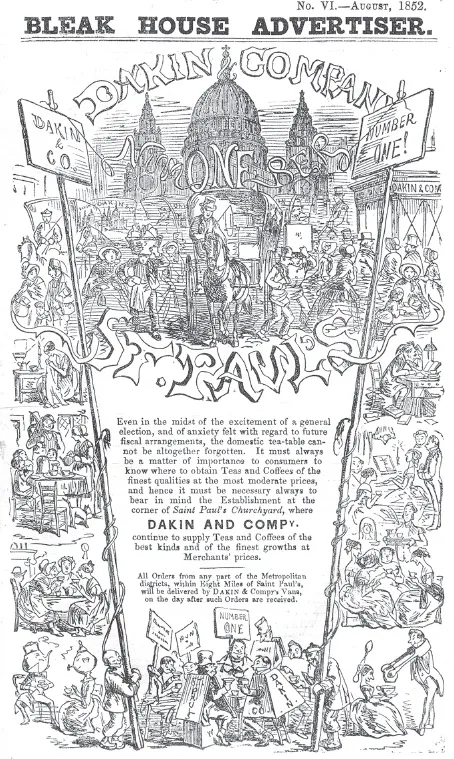

In Bleak House, Dickens purposefully works against this consequence; the narrative is straining against change, even as the narrator repeats individual acts in elaborate detail. In other words, the novel shows cyclicality to be a construction, borne of a wilful dedication to repetition that denies repetition’s inherent dynamics. As I shall show, Bleak House is a novel which acknowledges the constructed quality of repetitive time, and which hints, at various points, at the erasures that make this possible. One erasure is the possibility of a future or a past; another erasure is the work of the novel’s shadowy servants. Finally, the chapter links the novel’s production of time with a particular advertisement in the ‘Bleak House Advertiser’, the advertising supplement which was sown into the covers of the initial serial publication in 1852–3. Bleak House was published in 19 instalments, each containing 32 pages of the novel (apart from the 19th, which was a double number). Each instalment was bound in blue-green paper covers with a cover illustration by Hablot Knight Browne, under the familiar pseudonym ‘Phiz’ (Figure 1.1). The ‘Bleak House Advertiser’ both precedes and follows the novel. The advertisement I want to focus on below, for the tea and coffee company Dakin & Co., both invests in and elaborates on Dickens’s desire to construct a reproducible domestic time for the nation.

Bleak House has a stake in representing domestic time as a national allegory. Not only can domestic time be repeated in time (being inherently repetitive), but it can also be repeated across space, in other domestic spheres, by other families, simultaneously. Dickens had a well-documented dream of the many simultaneous domestic readings he could achieve with his serial format each time a new number was released. In the ‘Preliminary Word’ to his periodical Household Words, he writes:

We aspire to live in the Household affections, and to be numbered among the Household thoughts, of our readers […] We have considered what an ambition it is to be admitted into many homes with affection and confidence; to be regarded as a friend by children and old people; to be thought of in affliction and in happiness; to people the sick room with airy shapes ‘that give delight and hurt not’, and to be associated with the harmless laughter and the gentle tears of many hearths.5

The periodical text, being reproducible, will produce near-identical affective responses from its many readers. The aspiration is that synchronous readings will tend towards uniformity. Similarly, the monthly parts of Bleak House, with their recognizable blue-green wrappers and the distinctive cover design by ‘Phiz’, created a nationally synchronized reading time which could be domestically situated. The paratext of the Bleak House serial – the blue-green covers and the numerous advertisements in the ‘Bleak House Advertiser’ which accompany the letterpress – thus informs the novel’s aim to construct a national (domestic) time. Matthew Rubery has even spoken of a ‘Bleak House-time’, one produced by the novel and its paratext together. All 19 months were unified by their implication in the print run of Bleak House.6 In this chapter, I follow the lead of Laurel Brake who has similarly argued that ‘publishing histories of individual texts themselves may […] be said to participate in the paradigm of the timespan of the series which marked the period’.7 By ‘marking the period’ of Bleak House, both visually and through explicit references to Dickens’s novel, the ‘Bleak House Advertiser’ helped build the paradigm of that timespan, as Brake suggests.

Figure 1.1 Cover of the Bleak House serial, no. VI (August 1852)

Contemporary buyers of Dickens’s serial novel would be familiar with the engraved cover illustrations, which often contain oblique references to the novel’s themes. But in the sixth number, published in August 1852, the first sight that meets the reader upon turning the green front cover is a visual echo of that same front cover. It is an advertisement for Dakin & Co., tea and coffee sellers, deliberately designed to resemble the Bleak House cover (Figure 1.2). Dakin & Co., the firm behind this visual imitation, was a habitual and somewhat audacious advertiser in the ‘Bleak House Advertiser’. This particular illustration in the sixth number is so similar in design to Browne’s cover that a first-time reader is likely to pause for a moment, confused at the unexpected new beginning; in fact, there is little doubt that Browne is the artist responsible for both Dickens’s cover and Dakin & Co.’s advertisement. That the tea warehouse is using the Dickens serial as a vehicle obviously suggests how recognizable the Dickens brand had become. The Dakin & Co advertisement shares Dickens’s investment in the dream of innumerable domestic spheres, all of them leafing through the latest Dickens serial at once. Domestic time is central not just to the novel-text itself. As we shall see below, the Dakin & Co advertisement ties domestic time to the commercial distribution of print – novel, flyer, and advertisement – and suggests that ideal domesticity is reproducible (given the right brand of tea). Similarly, in Bleak House, repetitive actions are a model of behaviour. By using repetition formally, the novel posits that with the right practices, readers can reproduce Esther Summerson’s ideal domestic sphere, in synchrony, across the nation. Repetition, in other words, is set up as a producer of stasis and sameness. As I explain below, the narrative goes to inordinate lengths to maintain a viable stasis.

This chapter examines, first of all, traces of repetitive action in Bleak House. Repetition, by the very nature of the novel genre, is always represented pars pro toto; a novel that contained every instance of repetitive actions would be literally endless. Gérard Genette, in Narrative Discourse, distinguishes between narratives with recurrent events, and narratives where a single instance of an event is made to stand for many recurrences – he calls the latter ‘iterative narrative’.8 The distinction is a useful one: almost all of the instances of domestic recurrence in Bleak House are iterative (not every meal in the Bagnet family is narrated). Susan Stewart, in On Longing, discusses such narrative sleights of hand that represent repetition:

Figure 1.2 Dakin and Company advertisement in the Bleak House serial, no. VI (August 1852)

The temporality of everyday life is marked by an irony which is its own creation, for this temporality is held to be ongoing and nonreversible, and, at the same time, characterized by repetition and predictability. The pages falling off the calendar, the notches marked on a tree that no longer stands – these are the signs of the everyday, the effort to articulate through counting. Yet it is precisely this counting that reduces difference to similarities, that is designed to be ‘lost track of.’ Such ‘counting’, such signifying, is drowned out by the silence of the ordinary.9

When a narrative represents repetitiveness, individual instances are erased. One example of a dreary evening must stand for months of monotony in, say, Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South (1854–5). As Caroline Levine and Mario Ortiz-Robles have recently argued, nineteenth-century novelists became increasingly interesting in repetition both as a formal quality of narrative, and as a trope in itself:

repetitions might seem to act as a drag on narrative, unnecessarily elongating the text – making too much of the middle. And yet, narrative cannot do without repetition. Narrative theory has insisted on this point at least since Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, who argued that there can be no narrative without a subject who appears again and again, marking the passage of time for us through successive appearances. And the nineteenth-century English novel allows us to reconceptualise this property of narrative not only as a formal fact but also as a fact of social life. Repetition allows Victorian writers to reflect, and reflect on, the problem of mundane contemporary existence: such as the ordinary sameness that characterizes daily life, or the recurrent habits and manners that allow us to identify distinct social groups, or the dreary mechanical routines of factory labour.10

Repetition, Levine and Ortiz-Robles point out, seemed particularly pertinent to modern experience: it coloured work life, social interactions, the daily commute, and it characterized the everyday experiences that nineteenth-century novelists came to elaborate and investigate. Here Levine and Ortiz-Robles outline the two main meanings of the word ‘repetition’: first, the denotation of a narrative strategy, and second, as a trope in itself. Repetition can mean both repetitions of events and repetitive events. Following this argument, repetition becomes a trope of mid-century modernity itself – one associated with quotidian urban life and with the middle class’s self-identified perseverance. Bleak House aligns with this careful tracing of repeated actions which single-mindedly produce the same thing over and over again, regardless of place or circumstance, as I will show below. What later in the century would become tedium – in Our Mutual Friend the soulless drive of Podsnappery – is here the key to stability in the face of accelerating change.

Round and round: Bleak House and cyclicality

There is politics and poetics in repetition. In Bleak House, repeated actions are productive: if they produce nothing else, such actions produce sameness, the important maintenance that props up middle-class domesticity. Without seemingly working towards anything, characters in the novel seem to be working to prop up time itself. Early in the novel, the narrative can make do with an idealized archetype for uncomplicated domesticity: the school to which Esther Summerson is sent after her aunt’s death. Greenleaf becomes Esther’s first real home, and the place where she identifies herself with the role of comforter and manager. It is a little haven of exactness, reduced to narrative cliché: ‘Nothing could be more precise, exact, and orderly, than Greenleaf. There was a time for everything all round the dial of the clock, and everything was done at its appointed moment’ (34).

We recognize the model from Wilson’s clockwork house in the Introduction: a sparse and simplified conceptualization. At this extreme low end of representation, order is absolute. The ‘dial of the clock’ works as a simple visualization to link domestic time with circularity, recurrence, and stability. One thing follows another like beads on a string: nothing overlaps or spills or grinds to a halt. The school suggests an unproblematic, translatable, and essentially unproductive conceptualization of domestic time. When reduced to a clock-dial symbol, repetition can produce only stasis – tropes of repetition allow for narrative erasure of actual activity. However, it is only in such a foreshortened form that domestic time can uphold such stasis. Once repetition is articulated, and no longer just iterative or symbolic, stasis must be ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Timetabling and its Failures

- 1 Repetition: Making Domestic Time in Bleak House and the ‘Bleak House Advertiser’

- 2 Interruption: The Periodical Press and the Drive for Realism

- 3 Division into Parts: Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South and the Serial Instalment

- 4 Decomposition: Mrs Beeton and the Non-Linear Text

- Coda: Scrapbooking and the Reconfiguration of Domestic Time

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index