This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Heightened tensions in the South China Sea have raised serious concerns about the dangers of conflict in this region as a result of unresolved, complex territorial disputes. This volume offers detailed insights into a range of country-perspectives, addressing the historical, legal, structural, regional and multilateral dimensions of these disputes

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Territorial Disputes in the South China Sea by J. Huang, A. Billo, J. Huang,A. Billo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Peace & Global Development. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Origins

1

Origins of the South China Sea Dispute

Nguyen Thi Lan Anh

As with most territorial disputes, the ones that emanate from the South China Sea are extremely complex and multi-layered. The contested status of the territorial features in the sea are rooted in the region’s deep colonial history on one hand, and the legal regime of islands in accordance with international law on the other. The geostrategic importance of these features and the presence of rich natural resources around them have culminated in uneasy tensions in the South China Sea region between multiple states that claim sovereignty over the features. This has been fuelled by domestic politics and the rise of nationalism within certain claimant states. This chapter aims at providing an overview of the various layers that have contributed to the current complexity of the South China Sea dispute. It also highlights the challenges preventing the parties from reaching a resolution of the dispute in the near future. To arrive at this, it will first discuss the early history of the region in the colonial period. It then examines the influence of different factors, such as international law, economics, the geo-strategic significance of features, and the domestic situations in claimant states that trigger the South China Sea dispute.

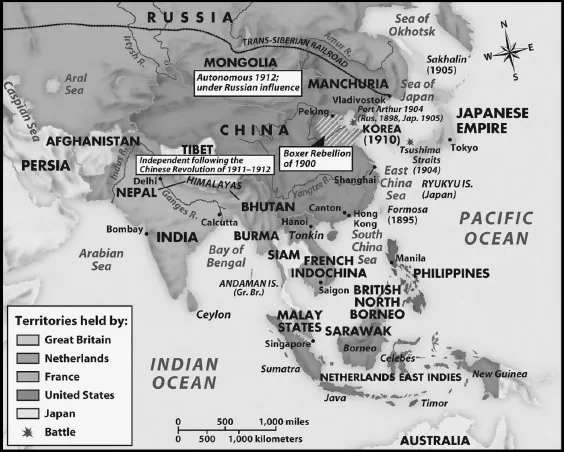

Colonisation: Early Beginnings of the Dispute

Before the presence of colonies in the region, the Persians, Arabs, Indians, Chinese, and the people of Southeast Asia used various sea routes in the South China Sea for trade. The islands and territorial features – which are the subject of the disputes as they exist today, existed as points on trading networks, or as navigational markers. The colonial footprint over the region emerged as early as the sixteenth century. The United Kingdom, France, Netherlands, and Spain entered the South China Sea with the aim of establishing trading stations and natural resource suppliers in the region. They divided the littoral territories of the South China Sea into their respective spheres of influence, namely, Malaya, the northern Borneo colonies, and Hong Kong (the United Kingdom), Indo-China (France), East Indies (the Netherlands), and the Philippines (Spain). The Portuguese maintained a short colonial presence in the East Indies before its occupation by the Netherlands. Similarly, the Americans followed the Spanish in occupying the Philippines. Additionally, the region witnessed the rise of Japan and its southeastwardly expansion to China, Vietnam, and some features in the South China Sea.

As an ocean that connects all littoral territories of Southeast Asia, the South China Sea has been used for centuries due to its vital location. Western colonialism established empires in Southeast Asia due to the maritime routes in the South China Sea. Several archipelagos in the South China Sea were marked and named on world maps by Western adventurers and colonisers. For instance, the name “Amphitrite,” given to a group of territorial features in the Paracels, stems from the shipwreck of the Amphitrite under the reign of King Louis XIV in 1698, when it was on its way to China from France (Madrolle, 1939).1 The Spratly islands received their name from British seafarers in 1762. In 1821, the British Admiralty published charts for the South China Sea (Hancox & Prescott, 1995; Odgaard, 2002, p. 64). In 1864, the British Royal Navy ship, HMS Rifle, reportedly came across a few islands situated in the South China Sea. The islands received their name from the captain who carried out the discovery, Richard Spratly.

Figure 1.1 Territories colonised in Southeast Asia.

Source: Hunt, Martin, Rosenwein, Hsia, and Smith, 2005.

The Paracels and Spratlys are two groups of islands occupying vast areas in the middle of the South China Sea. The Paracels contains the groups of Amphitrite and Crescent and some other adjacent islands and features. It covers an area of 305 square kilometres. The shortest distances from the Paracels to the Hainan Island of China and the Ly Son Island of Vietnam are approximately 140 nautical miles and 123 nautical miles respectively. The Spratlys even covers a much larger area of 160 square kilometres. The shortest distances from littoral states to the centre of the Spratlys is measured as about 200 nautical miles from the Brooke’s Point of the Philippines, 330 nautical miles from the Southern coast of Vietnam, 247 nautical miles off the coast of Malaysia, 405 nautical miles from southern islands in the Paracels archipelago, 540 nautical miles from the Hainan Island of China, and 860 nautical miles from Taiwan.2

Before and during the early stages of the colonial period, the Paracels and Spratlys appeared in the world navigation maps as dangerous grounds in busy navigation routes of the South China Sea. However, their mere presence in these maps sowed the seeds for sovereignty disputes for a long time to come.

In 1877, the British colony of Labuan, an island to the North of Borneo, issued a license for a group of businessmen to plant the British flag on the Spratly Island and use them for commercial purposes. The group’s search for guano stopped after a killing incident, hence no flag was planted (Catley & Keliat, 1997, p. 6).3

In 1927, the French began occupying the islands when they carried out patrol trips in the South China Sea to combat smuggling and conduct scientific surveys of the Paracels and Spratlys islands.4 In April 1930, during the second expedition to the Paracels and Spratlys by the ship La Malicieuse, France declared its formal possession of the Paracels and Spratlys by hoisting a French flag on the highest point of an island called Ile de la Tempete (Monique, 1996, p. 44: note 4). On 26 July, 1933, France formally declared its sovereignty over the Paracels and Spratlys and took physical possession of the archipelagos. It was noteworthy that the declaration clearly stated the name of some features in the Spratlys (as they exist today), such as the Spratly Island, Amboyna Cay, Itu Aba Island, Sin Cowe Island, Loaita Reefs, Thitu Island, and Northeast and Southeast Cays as well as all adjacent reefs and shoals (JROF, 1933, p. 7837).5 The declaration was also followed by marking a stone pillar on which was written “République Francaise – Royaume d’Annam – Archipel des Paracels 1816 – Ile de Pattle – 1938” (Republic of France – Royal of Annam – Paracels Archipelago 1816 – Pattle Island) (Monique, 1996, p. 46: note 4).6

The first to protest against the French sovereignty declaration of 1933 was Japan, on the grounds that the archipelago had been mined for years by various Japanese phosphate companies (Catley and Keliat, 1997, p. 25, note: 5). Japan’s interest in the South China Sea region began in the early twentieth century after it occupied Taiwan in 1895 and the Pratas Island in 1907 (Samuels, 1982, p. 63: note 6). Ho Ji Nien who was granted the exploitation rights by the Guangtung Province authority to exploit phosphate in the Paracels was actually backed by Japanese phosphate companies based in Taiwan. During the late 1920s and early 1930s, Japanese phosphate companies also began operating in the Spratlys (Samuels 1982, p. 63: note 6). While Japanese engagement in the archipelagos was limited to economic interests, it did not make any sovereignty claim until it protested against French claims and occupied the Paracels and Spratlys by force in 1939. During the Second World War, Japan maintained its occupation and placed the two archipelagos under the jurisdiction of the Governor General of Taiwan through the Kao-hsiung District (Samuels 1982, p. 63: note 6).

Despite the fact that the validity of each acquisition activity may be challenged, the discoveries and occupations during the colonial period have been used by claimants to justify sovereignty over the Paracels and Spratlys, even now. Taiwan’s claim is partly based on the occupation of Japan. Similarly, Vietnam’s claims are derived from the succession of the sovereignty declaration and occupation of France. After gaining independence in 1984, Brunei inherited a continental shelf partially delimited by the United Kingdom, based on which it already protested against the Malaysian claim to the Louisa Reef on its 1979 map.7

The Second World War ended with the cease of occupation by Japan and France in the Paracels and Spratlys, still leaving the fate of the archipelagos unclear. There were four international documents, namely the San Francisco Treaty, The Cairo Declaration, The Potsdam Declaration, and the Joint Communiqué between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Japan. The Cairo Declaration of 27 November 1943, was issued by the United Kingdom, United States, and Chiang Kai-Shek’s Nationalist China. The Potsdam Declaration of 26 July 1945 and the Joint Communiqué of 29 September 1972 between the People’s Republic of China and Japan addressed the issue of territories occupied during the Second World War by Japan. Nevertheless, none of these gave an explicit or decisive answer to the question of the sovereignty of the Paracels and Spratlys.

In the Treaty of Peace with Japan (also known as the San Francisco Treaty), Japan declared that it “renounces all right, title and claim to the Spratlys Islands and the Paracels Islands.”8 It did not however explicitly determine the status of the sovereignty of the Paracels and Spratlys after the Japanese renouncement.

The Cairo Declaration stated that it was the purpose of the Allied Powers to strip Japan of “all the islands in the Pacific which she seized or occupied since the beginning of the First World War in 1914, and that all the territories that Japan had stolen from the Chinese, such as Manchuria, Formosa and the Pescadores, shall be restored to the Republic of China” (Cario Declaration, 1943). This Declaration excluded the Paracels and Spratlys from the “stolen territories to be restored to China” (the Manchuria, Formosa and the Pescadores). It still did not, however, clarify the sovereignty status of the Paracels and Spratlys.

The Potsdam Declaration stated that, “the terms of the Cairo Declaration shall be carried out and Japanese sovereignty shall be limited to the islands of Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushsu, Shikoku and such minor islands as we determine” (Potsdam Declaration, 1945, para: 8).

The relevant contents of the Cairo Declaration and Potsdam Declaration were again transferred and reaffirmed in the Joint Communiqué between China and Japan. Point 3 in the Joint Communiqué provided that, “the Government of the People’s Republic of China reiterates that Taiwan is an inalienable part of the territory of the People’s Republic of China. The Government of Japan fully understands and respects this stand of the Government of the People’s Republic of China, and it firmly maintains its stand under Article 8 of the Potsdam Proclamation” (JMFA, 1972).

The lack of clarity regarding the sovereignty of the islands in these legal documents paved the way for different and conflicting interpretations (Valero, 1994). China and Taiwan assimilated the Paracels and Spratlys with those given to them under the Cairo Declaration. Vietnam based its claims on the French occupation and declaration. Moreover, they reaffirmed their claims since the Cairo Declaration excluded the Paracels and Spratlys as stolen territory by the Japanese from China. Since the end of the Second World War, given the lack of clarity in the status of the two island groups, the Philippines regarded them as terra nullius, or belonging to no one, thus giving other countries the freedom to make claims.

Development of International Law

Given the complicated and murky history of the sovereignty of the Paracels and/or Spratlys, some claimants have, independently or through their colonial masters, made various attempts to assert their sovereignty over them. Arguably, the significance and legal validity of these attempts can only be concluded by application of international law. There are three sets of international law governing the South China Sea dispute. These include the Law concerning Territorial Acquisition, the Law of the Sea and the Law on Dispute Settlement. This section analyses the extent to which the application of international law can help claimants resolve territorial disputes in the South China Sea region. It also discusses whether international law itself, due to its ambiguity or imperfectness, has exacerbated the dispute. In other words, it questions the extent to which International Law is the root and solution of the highly multi-layered issue.

The first set of rules that could be applied to the dispute is the law concerning territorial acquisition. Having originated from the West, the law has been crystallised under customary international law. Under this, a title to territory can be obtained through five modes: occupation, prescription, cession, conquest and accession (Brownlie, 2003, p. 123; Shaw, 2003, p. 409; Malanczuk, 1997, p. 147; Jennings & Watts, 1992).9 If a territory is considered terra nullius, it is open to acquisition through legal process of occupation.10 This process begins with its discovery, which crea...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction: Unknotting Tangled Lines in the South China Sea Dispute

- Part I Origins

- Part II Legal Dimensions

- Part III The Role of ASEAN: Challenges and Choices

- Part IV Regional Perspectives

- Part V Solutions and Future Prospects

- Conclusion: Harmony from Disunity: Core Issues and Opportunities in the South China Sea

- Index