- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Banks are entering a new environment. Regulation and supervision are becoming tougher, so that banks will be less likely to fail. If a bank does fail, bail-in rather than bail-out will be the new resolution regime, so that investors, not taxpayers, bear loss. Safe to Fail sums up the challenges that banks will face and how they can meet them.

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

1

“Too Big to Fail” Is Too Costly to Continue

Finance is central to the growth and development of the world economy, and a relatively small number of global systemically important financial institutions (G-SIFIs) are central to finance. But this interdependency is dangerous. The failure of one or more G-SIFIs could disrupt financial markets and put the world economy into a tailspin. Even if such a decline could be arrested, it may take many years before output again reaches its pre-crisis level and many more before it attains levels consistent with the pre-crisis trend of growth rates. Thus, crises can be quite costly, particularly if they permanently scar the economy (see Figure 1.1).1

A case in point is the “Great Recession” – economist-speak for the sharp downturn and sluggish recovery that followed the bankruptcy of Lehmans in 2008.2 In fact, the Great Recession is already one of the costliest crises on record. At the start of 2014, output remained well below what it would have been had growth continued at the pre-crisis trend rate and in some markets, notably the United Kingdom and most countries in the Eurozone, output remained below pre-crisis levels. Like a boxer who has struggled back to his feet after having been knocked down, the world economy is shaky. In such a situation, another financial crisis could deal the world economy a knock-out blow.

Figure 1.1 Crisis depresses global GDP

Should such a crisis recur, governments would be hard pressed to respond as they did in 2008, when they provided vast amounts of solvency and liquidity support to banks and other financial institutions. This support has, along with the recession itself, reduced the capability of governments to respond to a future crisis, should one develop.

So it makes sense to reform regulation and supervision, for doing so can reduce the likelihood and/or severity of any future financial crisis. However, financial intermediation requires financial institutions to assume risk if they are to contribute to growth and development. If financial institutions are to do their job properly, they cannot be failsafe. So it also makes sense for regulation and supervision to assure that finance can in fact take – in a controlled manner – the risks appropriate for an intermediary to assume.

In short, regulation and supervision have to strike a balance between stability and growth. The key to doing so is reforming resolution, so that failing financial firms can be reorganised and restructured without cost to the taxpayer and without significant disruption to financial markets or the economy at large. That will promote stability, for it would very significantly reduce the probability that the failure of one firm, however large and however complex, could trigger a financial crisis. And that in turn will allow regulation and supervision of banks and other financial institutions to focus on assuring that financial firms are taking and managing risk properly rather than forcing such firms to avoid risk entirely. In other words, if financial firms can be made safe to fail, they need not, indeed should not, be made failsafe.

Finance is central to growth and development

Finance makes two contributions to growth and development. It makes investment more productive, and it augments the amount of investment that takes place.

To see why this is the case, imagine a world without finance. Investment would be restricted to projects that a firm or family could afford to pay for out of their current resources. That would limit total investment and reduce its productivity. Many good projects with high risk-adjusted returns would simply not make it to the drawing board, much less off it.

In effect, finance allows issuers – the users of capital – to compete for the accumulated savings that investors have at their disposal. Hence, there is flow of capital to projects with higher risk-adjusted returns. This raises the yield on investment and makes saving more attractive, increasing the volume of saving and therefore investment.

The job of finance is to assure that this competition does in fact take place; that it is fair to both issuers and investors and that prospective returns are aligned with the risk to which the investor is exposed. To do its job of promoting growth and development, the financial system has perhaps above all to generate liquidity. It has to transform long-term illiquid assets (e.g., loans) into short-term liquid liabilities (e.g., deposits) and/or it has to allow investors to sell or buy assets without the mere act of their placing an order causing the price of the asset to fluctuate.

To achieve such a maturity transformation or to generate such market liquidity for investors, the financial services firm must itself assume a variety of risks – credit, interest-rate, exchange rate, counterparty, operational, and so on. It is the job of each financial firm to manage these risks. And it is the job of regulators and supervisors to

•ascertain that financial institutions exhibit good conduct and punish those who don’t; and

•confirm that financial institutions remain in good condition (meet threshold conditions) and put into resolution those who don’t.

It is not the job of regulators or supervisors to make banks failsafe. That can’t be done, or at least it can’t be done without undermining the very function – risk-taking – that makes banks socially useful.

Global systemically important banks are at the core of the financial system

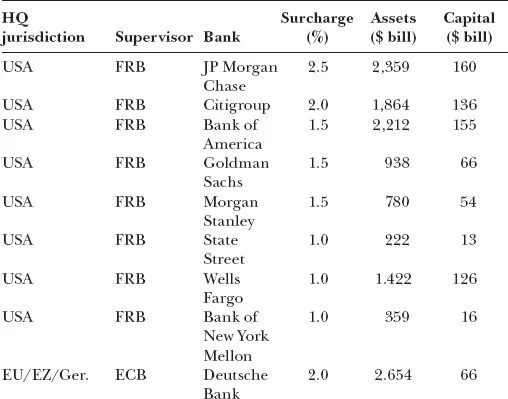

At the heart of the financial system are the 29 banking groups designated as global systemically important banks (G-SIBs; see Table 1.1).3 Collectively, they account for a very significant share, if not the bulk of the world’s financial activity. Without reform of resolution, the failure of any one of these institutions could have severe repercussions on financial markets and on the world economy.

Table 1.1 G-SIBs as of November 2013

Of the 29 G-SIBs 16 are headquartered in Europe, 8 in the United States, 3 in Japan and 2 in China. Supervision of G-SIBs will fall predominantly to two institutions: the ECB (after banking union becomes effective, it will directly supervise 9 G-SIBs) and the US Federal Reserve System (8). The Bank of England’s Prudential Regulatory Authority will also play a significant role, as the home supervisor of the 4 G-SIBs headquartered in the United Kingdom and as the host-country supervisor for the activities of the other 25 G-SIBs in the world’s primary international financial centre.

Collectively, the G-SIBs account for approximately 40 per cent of the total Tier 1 capital and total assets in the global banking system (see Table 1.1). They also account for the dominant share of activity in key financial markets (see Table 1.2). In payments, nine out of the top ten banks in international cash management services are G-SIBs. Collectively, G-SIBs have over $100 trillion of assets under custody, over 65 per cent of the total assets under custody. Eight of the top ten custodians are G-SIBs. In foreign exchange, G-SIBs account for over 90 per cent of FX trading, and each of the top ten players in the FX market is a G-SIB. In loan syndication, bond underwriting and equity underwriting the story is similar. G-SIBs account for over 70 per cent of total volume and at least nine of the top ten players in each market is a G-SIB. In addition, each G-SIB is generally a leading player in the domestic retail market. Many G-SIBs have millions of retail customers (with the largest having a customer base of over 100 million individuals).

Table 1.2 G-SIBs account for the bulk of activity in key products

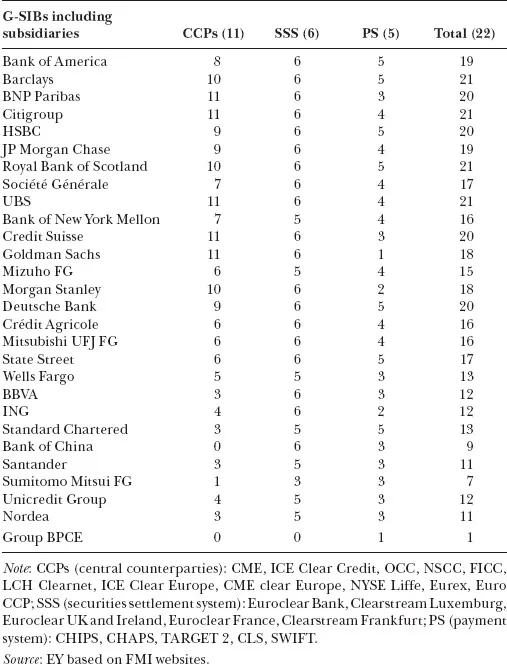

G-SIBs are also the principal participants in financial market infrastructures (FMIs), such as payment systems, trade settlement systems (e.g., for foreign exchange, loans and securities) and central counterparties (CCPs) (see Table 1.3). Hence, the failure of a G-SIB could put several FMIs under pressure at the same time. This could pose a significant threat to financial stability, for FMIs are “single points of failure.” If the failure of one G-SIB causes an FMI to fail, this could topple over other G-SIB participants in the FMI. This could in turn cause disruptions in financial markets and in the economy at large.4

Table 1.3 G-SIBs participate in multiple FMIs

Containing the current crisis has exhausted the capability of governments to respond to another crisis

That economists speak of “The Great Recession” rather than “The Great(er) Depression” is eloquent testimony to the success of the policy measures that policymakers took in 2008 and 2009.5 But these measures have reduced fiscal flexibility and largely exhausted the range of options open to monetary policy. Were another financial crisis to occur, governments would find it difficult if not impossible to respond as they did in 2008 and 2009.

Support for financial institutions contained the crisis

During the crisis governments provided massive amounts of support to their banking systems. This prevented contagion and limited the number and severity of failures. Either directly or in conjunction with central banks, governments injected equity into financial firms, guaranteed firms’ borrowing in capital markets, increased deposit guarantees, provided credit to firms and supported, via massive acquisition programs, the price of asset-backed securities. Total direct assistance to the financial sector amounted to over 80 per cent of GDP in the United Kingdom and to nearly 75 per cent of GDP in the United States (see Figure 1.2).

But fiscal flexibility has evaporated

As a result of the support given to financial institutio...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction: Resolvability Will Determine the Future of Banking

- 1 “Too Big to Fail” Is Too Costly to Continue

- 2 Less Likely to Fail: Strengthening Regulation

- 3 Less Likely to Fail: Sharper Supervision

- 4 Safe to Fail

- 5 Setting Up for Success

- Conclusion: Is Basel Best?

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Safe to Fail by T. Huertas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Financial Risk Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.