This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Internationalisation has had a forceful impact on universities across the Anglophone world. This book reviews what we know about interaction in the Anglophone university classroom, describes the challenges students and tutors face, and illustrates how they can overcome these challenges by drawing on their own experiences and practices.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Classroom Interaction by Doris Dippold in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Pedagogía & Enseñanza de idiomas. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

PedagogíaSubtopic

Enseñanza de idiomas1

Internationalisation and University Policies

Abstract: This chapter introduces key terms of this book, for example, internationalisation, internationalisation at home vs. internationalisation abroad and internationalisation of the curriculum. It describes how these terms relate to classroom interaction and why it is relevant to think about classroom interaction in the Anglophone higher education (HE) classroom.

Through a documentary analysis of the policies and strategies of a sample of 12 UK universities and of other key stakeholders within the UK HE arena, the chapter further shows how higher education institutions (HEIs) conceptualise internationalisation. It also discusses how classroom interaction fits into these conceptualisations regarding the tutor and student support mechanisms.

Keywords: classroom interaction; internationalisation; internationalisation abroad; internationalisation at home; internationalisation of the curriculum

Dippold, Doris. Classroom Interaction: The Internationalized Anglophone University. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. DOI: 10.1057/9781137443601.0007.

This chapter

This chapter sets the scene by defining the key concepts of the title in this publication: internationalisation and related notions, such as internationalisation of the curriculum, internationalisation at home and internationalisation abroad. It then relates these concepts to our core area of concern for this book – classroom interaction – and describes the central position of classroom interaction in universities’ educational mission. It closes by reviewing, by way of documentary research, the policies and practices of key stakeholders in UK higher education (HE) as well as those of a sample of UK universities, in particular in relation to the terms internationalisation of the curriculum, internationalisation at home and internationalisation abroad.

Defining internationalisation

Internationalisation rationales

Jane Knight (2004), one of the most eminent scholars on internationalisation of HE, defines internationalisation as

the process of integrating an international, intercultural or global dimension into the purpose, functions or delivery of post-secondary education. (p. 11)

Knight thus emphasises that internationalisation (1) is an ongoing process into which institutions need to invest (time and resources); (2) should be part of the aims and purpose of an institution, not just an incidental by-product; (3) needs to be integrated into services of an institution; (4) needs to be integrated into the delivery of education and (5) includes cultural interaction, as betrayed by the term “intercultural” included in the definition.

Internationalisation is driven by a wide range of rationales: from economic reasons (student recruitment, income generation) over social and cultural rationales (e.g., fostering intercultural understanding) political rationales (promoting peace and mutual understand) through to academic (e.g., research collaboration, curriculum development), competitive (profile/reputation building and branding) and developmental drivers (e.g., promoting student and staff development) (Knight, 2004; Middlehurst and Woodfield, 2007).

Not surprisingly, economic rationales – often counteracting decreases in public funding – are at the forefront of many HE institutions’ (HEIs’) strategic thinking about internationalisation: in 2011–2012, UK universities received revenue of £3.2 billion in tuition fees from non-EU students, with students from the EU contributing £0.4 billion (Universities UK, 2014a). It is therefore hardly surprising that institutions and decision-makers within them frequently associate internationalisation with student mobility – in particular student flow into the receiving country.

However, it is generally acknowledged that the mere presence of international students (or staff) on campus will not create an international ethos (see Chapter 2 and 3 for more detail). In fact, “the more international students on campus the more internationalised the institutional culture will be” is, according to Knight (2011) one the five myths of internationalisation (p. 1).

Using the dichotomy of “symbolic” vs. “transformative” internationalisation, Turner and Robson (2008) suggest that only when universities move away from such purely economic concerns can internationalisation be developed from being a token, front-window activity to one that permeates the entire institution:

Symbolic internationalisation is exemplified by an organisation with a basically local /national character and way of doing things, but which is populated by a proportion of overseas students and staff. At the other end of the scale, transformative internationalization describes institutions where an international orientation has become “deep”, embedded into routine ways of thinking and doing, in policy and management, staff and student recruitment, curriculum and content. (p. 26)

In addition, Otten (2009) suggests that individual intercultural competence (of both students and staff) will allow institutions to move from a state of stagnation and “weak reflexivity of cultural issues” (p. 413) towards a transformative orientation, which will allow for new cultural practices and social rules to emerge.

The vital role of managerial and organisational input into internationalisation has also been emphasised by Söderqvist (2007) who, in investigating the implementation of internationalisation at Finnish universities in relation to policy, suggests that

based on an analysis of its external and internal environment it is desired in a public higher-education institution to actively and systematically manage a change process leading to including an international dimension in all parts of holistic strategic and operative management, namely information, planning, organising, financing, implementing and evaluating; financing being an important element in all of them, in order to enhance the quality of the desired outcomes of internationalisation in the higher-education institution in question. These desired outcomes can be grouped under teaching and research. Mobility, networking and management are the main tools for achieving them. (p. 43)

As we show in this chapter by reviewing the internationalisation policies and agendas of a sample of UK universities, one desired outcome of internationalisation which is frequently emphasised is the development of skills for global citizenship. These skills are also encapsulated in a model of the desired outcomes of internationalisation put forward by Deardoff (2006), namely internal outcomes such as adaptability, flexibility, ethno relative views, empathy and external outcomes such as effective and appropriate communication and behaviour in an intercultural situation.

In the next section, I consider further key concepts and terms in internationalisation debates, in particular “internationalisation at home” and “internationalisation abroad” and the way in which they relate to classroom interaction.

Internationalisation at home – internationalisation abroad

In descriptions of universities’ internationalisation activities and practices, the terms internationalisation abroad and internationalisation at home have established themselves. Though internationalisation abroad is generally used to refer to staff and student flows, international alliances for research and teaching, overseas campuses and so on, internationalisation at home describes “the embedding of international intercultural perspectives into local educational settings” (Turner and Robson, 2008, p. 15) or “the creation of a culture or climate on campus that promotes and supports international or intercultural understanding and focuses on campus-based activities” (Middlehurst and Woodfield, 2007, p. 30). Internationalisation at home includes all activities that make a campus an international one in ethos as well as in practice and is, according to Koutsantoni (2006b), a

whole institution activity [ ... ] and implies changes in attitudes as well as management practices and institutional policy. An inherent aspect of internationalisation “at home” is the appreciation of the diversity of language and culture by students and staff, and a commitment to equality and diversity. [ ... ] Internationalisation “at home” additionally involves the integration of international students in campus life and in the local community. (p. 19)

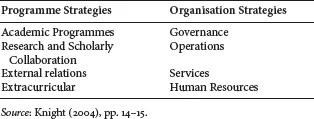

Knight distinguishes eight institution-level strategies for internationalisation, which I have summarised in Table 1.1.

Internationalisation at home is primarily implemented in two of the strategy clusters which are subsumed here under the label of programme strategies: academic programmes and extracurricular activities. However, it needs to be supported by organisation strategies from all four clusters outlined here: governance in terms of leadership commitment and policies, operations in terms of planning, budgeting and the creation of organisational structures, services such as staff training, induction or student support activities, and human resources in terms of recruitment, selection and rewards and enticement for staff to support internationalisation. In the review presented in the latter part of this chapter we primarily look at governance and internationalisation support at the level of student and staff services through our sample universities.

In current research, UK universities’ internationalisation efforts tend to be characterised as empty rhetoric, ethnocentric, guided by an assumption of the superiority of Western approaches to education and non-conducive to developing students’ intercultural capabilities (Caruana, date unknown; Robson, 2011; Ryan, 2011). For example, in a recent investigation (Al-Youseff, 2013), UK university managers viewed internationalisation as a vital financial strategy as well as a way of achieving cooperation and international understanding. However, most managers also tended to describe international students through their perceived difficulties in adapting to local learning styles (plagiarism, taking part in debates) and did not see a need for reciprocity in the development of intercultural understanding.

TABLE 1.1 Institution-level strategies for internationalisation

It is thus not surprising that Knight (2011) states that

In many institutions, international students feel marginalised socially and academically and often experience ethnic or social tensions. Frequently, domestic undergraduate students are known to resist, or are at best neutral, about undertaking joint academic projects or engaging socially with foreign students unless specific programmes are developed by the university or the instructor. International students tend to band together and ironically often have a broader and more meaningful experience on campus than domestic students but lack a deep engagement with the host country culture. Of course, this scenario in not applicable to all institutions but it speaks to the often unquestioned assumption that the primary reason to recruit international students is to internationalise the campus. (p. 1)

Moreover, as I show in more detail in Chapter 2, home students also often feel disassociated from internationalisation processes (Hyland et al., 2008; Trahar and Hyland, 2011). Public debates bemoan falling academic standards due to increasing intakes of international students (see Benzie, 2010; Devos, 2003) and generally betray a certain degree of angst in relation to internationalisation and its implications, perceptible for example in an online discussion sponsored by the Guardian (2014) under the title “Should academics adapt their teaching for international students?”

Internationalisation of the curriculum

A term frequently used in reference to the learning and teaching dimension of internationalisation is internationalisation of the curriculum. However, definitions of the concept differ somewhat in scope.

In a publication by the Leadership Foundation for Higher Education (Fielden, 2011) targeting HE governors, internationalisation of the curriculum is defined (p. 15) in terms of curriculum content, international subjects, internationally comparative approaches, internationally interdisciplinary programmes, preparation for international professional careers and joint/double degree programmes with international partners.

Turner and Robson (2008) suggest that approaches which focus solely on curriculum content and international programmes treat the internationalisation of the curriculum “as an exclusively cognitive matter” (p. 44), while Caruana (date unknown) detects a neglect of skills, attitudes and behaviours as elements of global citizenship. Other authors have thus emphasised the need for an internationalised curriculum to develop global citizenship (Leask, 2009; Sanderso...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 Internationalisation and University Policies

- 2 Student and Staff Perspectives

- 3 Pragmatics and Discourse Perspectives

- 4 Culture and Classroom Interaction

- 5 Responding to Classroom Interaction Challenges

- Conclusion

- References

- Index