eBook - ePub

Security, Clans and Tribes

Unstable Governance in Somaliland, Yemen and the Gulf of Aden

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Security, Clans and Tribes

Unstable Governance in Somaliland, Yemen and the Gulf of Aden

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Offering an introduction to clanism and tribalism in the Gulf of Aden area, Dr Lewis uses these concepts to analyse security in Yemen, Somalia, Somaliland and the broader region. This historical overview of conflict in each country, and the resulting threats of piracy and terrorism, will benefit both the casual reader and student of development.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Security, Clans and Tribes by A. Lewis,Kenneth A. Loparo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politique et relations internationales & Politique africaine. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Abstract: Economically and strategically, the Gulf of Aden is today one of the most important waterways in the world, with 7 per cent, according to James Kraska (2009), of world oil trade passing through it annually. However, it is surrounded by some of the most unstable and dangerous territories in the world – Yemen and Somalia – which are connected by it. As fragile and failed states, much is made of weak governance in these two countries. Each has been studied as a microcosm of terrorism, radicalisation, corruption, underdevelopment, and a wealth of other challenges. Yet this approach has been highly limiting. Closer investigation of the broader Gulf of Aden region reveals that these challenges are not nationally confined or nationally defined. Many are transnational. Others, due to large internal variation caused by the diverse manifestation of tribes and clans, are local. In both cases, a new framework of analysis is needed, one that looks at the whole of their territories and the Gulf of Aden at once.

Keywords: clans; failure; fragility; Gulf of Aden; security; Somalia; Somaliland; tribes; Yemen

Lewis, Alexandra. Security, Clans and Tribes: Unstable Governance in Somaliland, Yemen and the Gulf of Aden. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. DOI: 10.1057/9781137470751.0005.

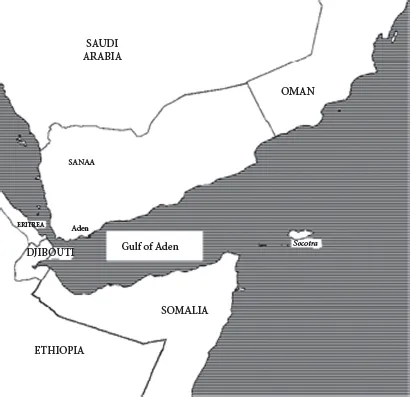

The Gulf of Aden and its surrounding countries comprise one of the most dangerous regions in the world, being home to multiple terrorist, insurgency, criminal and pirate organisations, most famously, perhaps, Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and Al Shabaab. The Gulf is located between the Arabian Sea and the Red Sea, and is bordered by Djibouti, Somalia’s Somaliland and Yemen. It is an important waterway of strategic and economic interest not only to the Horn of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula that are connected by it, but also to multiple other regions across the world, including Asia and Europe (with the latter accounting for 80 per cent of international maritime trade through the area in 2008 (United States Department of Transportation, 2009)). In 2009, James Kraska wrote that ‘[33,000] ships transit the Gulf of Aden annually – including some 6,500 tankers – carrying seven per cent of the world’s daily oil supply’ (p. 197), and these figures are likely to have increased by 2014. Yet, despite its significant international economic relevance, the Gulf of Aden has brought little financial benefit for its surrounding port towns, with neighbouring Yemen and Somalia emerging as two of the poorest and least-developed countries in the world – Yemen now being classed as a ‘fragile’ state by the international community, and Somalia being classed as a ‘failed’ or ‘collapsed’ one.

FIGURE 1.1 Map of the Gulf of Aden region

A major reason why neither of the Gulf’s main harbour countries has been able to capitalise on this lucrative trade route has been the critical threat level associated with the region, with Yemen and Somalia in particular being commonly linked in the media with conflict and high levels of social chaos. These critical security threats – along with regional organised crime networks that have emerged in response to economic disparities between the Middle East and North Africa – reflect a series of very real threats to international security and local development that remain little understood by traditional conceptualisations of statehood, fragility and failure, and by emerging analyses of tribal and clan-based conflicts.

In recent years, fragility and failure have emerged as dominant paradigms in the study of post-conflict reconstruction and severe state underdevelopment. With their focus on state capacity and stability, these concepts have been picked up by leading international donors, including the Australian Agency for International Development (AUSAID), the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the British Department for International Development (DFID), so as to move beyond rights-based and neo-liberal approaches to development, and to adopt ‘whole of government’ and collaborative governance perspectives on development planning (Unsworth, 2009, p. 885). Olivier Nay writes that ‘The global interest in the fragile and failed state issue partly results from substantial grants awarded by the US and British governments in the early 2000s’ to study and respond to underdevelopment and instability crises (2013, p. 328). In order to respond to resulting demands from large donors for evidence in improved policy planning, a plethora of frameworks and indices have been produced by various think tanks and aid agencies to furnish the required data and analyses, including, most notably, Foreign Policy’s Fragile States Index (Barakat et al., 2011, p. 11). Unfortunately, these frameworks and indices have prioritised bordered conceptions of fragility and failure that obscure local-level variations in the contexts that they study. This is problematic at a time when fragile states themselves the world over have become overrun by very region-specific and localised conflicts that cannot be understood at the national level alone. Additionally, in the case of Somalia and Yemen, a focus on state institutions obscures the important roles that clans and tribes play in upholding security or generating insecurity, as drivers of either stability or fragility and failure.

In one of his more commonly cited books, The Bottom Billion, Paul Collier writes that, in 2007, 73 per cent of people living in fragile settings were experiencing or had recently experienced civil war (p. 20). Now, in 2014, most fragile states are affected by some form of conflict: so much so that conflict itself has begun to be integrated into the very definitions of fragility and failure (with state failure denoting the dominance of social chaos over any governing institutions). Indeed, Alina Rocha Menocal, one of the leading experts on fragility, lists two core components of fragility as being ‘a state’s lack of authority or control over the whole of its territory’, and a state’s ‘lack of monopoly over the legitimate use of violence’ – two conditions that signal the presence of insurgencies and non-state combatants (2011, p. 1715). These are conditions that are either generated or aggravated in the Gulf of Aden region by the existence of competing non-state hierarchies, especially clan-based and tribal ones, which may have greater popular support than state institutions and may also be excluded from, or choose not to participate in, mainstream governance, creating a rival socio-political system of organisation for communities.

Lisa Chauvet et al. summarise: ‘The most basic role of the state is to provide physical security to its citizens’ (2007, p. 1) because, as Robert Rotberg concludes, ‘The delivery of a range of other desirable political goods becomes possible [only] when a reasonable measure of security has been sustained’ (2004, p. 3). Yet in certain regions of Yemen and Somalia, these services are disrupted by tribes and clans, or are directly provided by them. State fragility, which is fundamentally linked to an inability to deliver goods and services, is produced in settings where insecurity dominates, or results in insecure contexts, but the concept itself does not leave room for the analysis of how non-state hierarchies either produce or mitigate the effects of weak statehood. The reverse relationship, of how fragility impacts clan-based and tribal structures, is also omitted from the framework. Meanwhile, the dominance of insecurity over states is associated with state collapse, producing state failure, which either strengthens or obliterates non-state structures, depending on the context. Due to the scale of insecurity and governance challenges involved, Francis Fukuyama writes that ‘Since the end of the Cold War, weak and failing states have arguably become the single-most important problem for international order’ (2004, p. 92).

Somalia and Yemen, as failed and fragile states respectively, are bereft by internal divisions, with the continued existence of both countries being challenged and undermined by growing secessionist movements within them. In February 2014, Yemen strived to overcome these challenges by introducing a new federal system that at once sought to recognise its lack of internal uniformity and to bypass the entrenchment of tribal entities in local and national governance, which had created violent competition between tribal and non-tribal communities. However, the federalisation plan failed to address local grievances, maintaining the power-base of existing elites. Meanwhile, Somalia is being torn apart by the unrecognised separation of Somaliland and Puntland from the South Central Zone along clan divides, and by the creation of new mini-states within its territories. In the Gulf of Aden insecurity triangle, Yemen and Somalia emerge as primary examples of the limitations of bordered conceptions of state fragility and failure for adequately capturing and understanding the impact of the local level on peace and conflict, especially where clans and tribes are concerned, as this book will argue.

The language of fragility and failure, due to its associations with institutional weakness as well as to its strong focus on statehood and governance, also undermines positive achievements towards peaceful development, particularly in terms of its lack of examination of local resilience to violence and conflict. Why some communities flourish, establishing zones of peace, while others, in similar circumstances, succumb to social chaos is still poorly understood by contemporary research working off traditional conceptions of statehood or recent definitions of state fragility. Comparisons between Yemen and Somaliland (an autonomous self-declared state in Somalia) are especially difficult here. This limitation emerges perhaps from the reality that fragility and failure frameworks do not make room for the objective analysis of non-democratic and sometimes non-state or shadow structures that have key roles to play in the generation of either peace or conflict in underdeveloped states.

This book will attempt to provide a new analysis of security in the Gulf of Aden region by stepping away from bordered conceptions of fragility and failure to look instead at the role of clans, tribes, transnational flows and non-standard governance roles in shaping, challenging and consolidating statehood in difficult, interconnected and underdeveloped contexts. It will use regional and local lenses to analyse insecurity in Yemen and Somalia in order to understand how emerging challenges overlap and interact with one another across the Gulf of Aden waterway.

1.1The fragility of fragile and failed states in the Gulf of Aden area

Olivier Nay writes that the terms ‘fragile’ and ‘failed’ have gained prominence in policy, with failure emerging as a concept and being picked up predominantly in the United States (US) in the 1990s due to a radical spike in civil wars,1 and fragility being heralded in the 2000s as an internationally accepted term, used to ‘designate the poorest and most unstable countries that cannot meet minimum standards set by major donors of development aid’ (2013, p. 327). Nay believes that ‘fragile state’ has since become ‘a generic and comprehensive category adopted by a large number of Western governments and international organisations since 2005, while “failed” and “failing states” remain more controversial notions despite their extensive use by US policymakers in the last decade’ (Ibid.). Fragility is a flexible term, allowing for the broad analysis of state ‘inability to provide basic services and meet vital needs, unstable and weak governance, persistent and extreme poverty, lack of territorial control, and high propensity to conflict and civil war’ (Bertocchi & Guerzoni, 2011, p. 2).

DFID define state fragility as characteristic of countries that are incapable of independently initiating progress towards the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (2006). Fragile states are also defined as countries containing governments that have not yet collapsed, though they may be ‘failing’, or ‘at risk of failing’ (Stewart & Brown, 2010). A necessary criterion of fragile states is that they retain a minimal amount of institutional capacity that allows them to continue to exert a concrete influence over their citizens and their territories. The label is used by international bodies to justify immediate assistance to governments to avoid state collapse. Confusingly, however, the terms ‘fragile’ and ‘failed’, because of their elastic definitions, are often used interchangeably.

Whatever the preferred term, the language of state fragility and failure is politically loaded, and has been rejected by those who:

[deny] the existence of a set of ‘fragile states’ that, when their economic aggregates are compared to governance aggregates, would be basically identical to the group of [least-developed countries]. This doctrine holds that each individual case of ‘fragility’ is absolutely unique, as impoverished but peaceful countries ... should not be treated in the same way as potentially rich states that are ravaged by civil war ... or regional crossroads with complex histories. (Châtaigner & Gaulme, 2005, p. 5)

Equally contentious is the association of the words ‘fragility’ and ‘failure’ with notions of weakness. This book links state fragility primarily to lack of institutional capacity and an inability by governments to streamline violent conflicts into the mainstream political process. It links failure to state collapse, a process leaving the government of a country without any capacity to control national politics or contain opposition fighters. However, neither term is without its problems and limitations.

Despite a clear need for a set of terms to describe various crises of underdevelopment, there are a number of challenges associated with using fragility and failure to explain socio-political instability. First, as Châtaigner and Gaulme explain, the danger of using the concept of state fragility is in that it frequently fails to take into consideration regional or international stress factors that may be weakening the ability of states to exert their authority (2005, p. 6). Likewise, local variation is overlooked, so that, even if one section of a country is performing extremely well according to a set of accepted development indicators, the state as a whole may still be considered fragile. While definitions of state fragility and failure vary, all of them take the state as their primary unit of analysis and therefore consider the phenomena at a national level. This focus means that solutions to fragility and failure are sought in state-building. As will be argued with reference to Somalia, this is not always appropriate.

Second, the fragility/failure frameworks are inherently backwards looking. They take a snapshot of a situation building up to, and including, the present, rather than projecting anticipated development trajectories. This emphasis is understandable within a climate where academic publishing is heavily restricted by critical review processes that allow only for immediately verifiable data to be released, but it slows the pace of policy responses to crisis that are based on analyses of fragility or failure.

Finally, associations of fragility and failure with weakness, combined with the focus of both frameworks on the state level, inherently obscure any progress made in nascent community-led development or non-governmental social order – proce...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Clans, Tribes and Social Hierarchies in the Broader Gulf of Aden Region

- 3 Somali Boundaries and the Question of Statehood: The Case of Somaliland in Somalia

- 4 Divide and Rule: Understanding Insecurity in Yemen

- 5 Transnational Security: Piracy, Terrorism and the Fragility Contagion

- 6 Conclusion

- Appendix: Getting to Grips with the Gulf of Aden: Levels of Analysis

- Bibliography

- Index