![]()

Part I

The Role of Productive Development Policies

1

Rethinking Productive Development

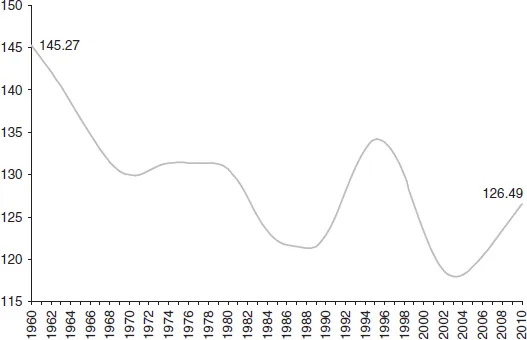

Latin America and the Caribbean is a middle-income region. The typical country in the region has an income per capita about 25 percent above the typical country in the world, but 80 percent below the income per capita of an advanced country like the United States.1 The region’s relative position is declining: 50 years ago, it was much better off than it is today compared to the rest of the world (ROW), and despite recent strides, it has been unable to converge with respect to the United States (Figure 1.1). Why is the region so much poorer than the advanced countries in the world? Why is the region lagging behind while other parts of the world are catching up with the leaders? And most important, what can the region do about it?

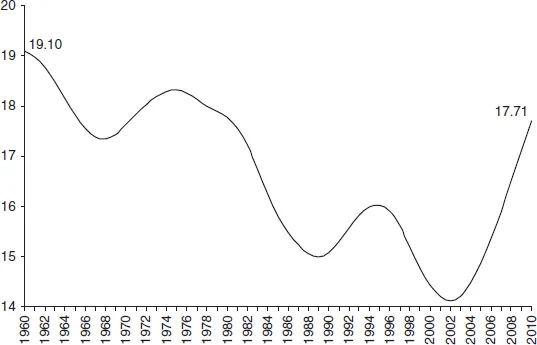

Behind the region’s disappointing performance in income per capita lie substantial shortfalls in its productive capabilities. Measured against the United States, workers are less productive because they have less capital and schooling with which to multiply the fruits of their labor. Important as these shortfalls in production factors are, however, they miss a key part of the problem. The main driver of the region’s disappointing performance, and the one factor on which to lock the policy radar, is the low productivity with which factors of production are utilized. In economists’ jargon, the key to understand the region’s underperformance is total factor productivity (TFP) (for details, see Daude and Fernández-Arias, 2010).

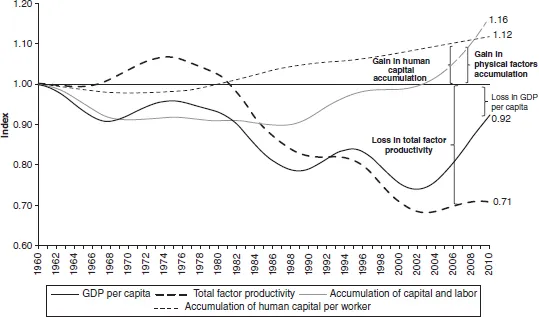

In fact, economic performance over the last 50 years has been held back by declining TFP compared to both the most advanced economies and the successful developing economies. Figure 1.2 shows that, relative to the United States, the typical country in the region has had faster factor accumulation (the gaps in both physical factors, capital and labor headcount, as well as schooling of the labor force have been reduced), but its gap in TFP has increased. In fact, the productivity gap greatly widened, from 27 percent to 48 percent (Figure 1.3). At the same time, the typical East Asian tiger2 narrowed its productivity gap significantly, from 51 percent to 33 percent.

Figure 1.1 Relative GDP per Capita (Percentage)

a. Typical Latin American Country vs. Typical Country from the Rest of the World

b. Typical Latin American Country vs. the United States

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Feenstra, Inklaar, and Timmer (2013).

Figure 1.2 GDP per Capita Decomposition: Typical Latin American and Caribbean Country Relative to the United States (1960=1)

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Fernandez-Arias (2014).

The region’s substantial productivity shortfall suggests an overarching policy objective: set the conditions to improve productivity to match the pace of other, better-performing countries. There are multiple ways to strive for this objective. Better productivity policies may aim at a better use of existing factors of production. This applies to resources not only within existing firms but also their reallocation from low- to high-productivity firms and sectors. Crucially, policies may also aim at better incentives for future factor accumulation to obtain sound productive transformation.

This report does not cover the entire public policy agenda that could be relevant for productivity improvement and faster growth along these fronts. For example, it does not discuss how to reduce low productivity in the informal economy, reform labor or financial markets to facilitate the overall efficiency of allocating factor inputs across the economic structure, structure fiscal revenues with productivity in mind, or improve the overall quality of the education system. In contrast, this report focuses specifically on policies directed to the activities of the productive sectors of a national economy, or productive development policies (PDPs) (Melo and Rodríguez-Clare, 2006). This policy focus is highly relevant but restrictive: faster growth and strong economic development require a successful balance across all fronts of the policy agenda, not only sound PDPs. The importance of each policy front and the appropriate time path of the policy mix depend on the stage of development and other country circumstances. PDPs by themselves are no panacea; they are part of the toolkit of policymakers concerned with economic development to complement the rest of the policy agenda outside the scope of the report.

PDPs vary widely and encompass both broad-based and selective policies, discussed in chapter 2 under the headings of horizontal and vertical policies, respectively. They include diverse areas such as promoting technological upgrades at the level of the firm; encouraging the creation and growth of high-impact, high-productivity firms; stimulating efficient collaboration among firms to resolve coordination problems at the sector level; ensuring that public goods such as infrastructure are provided appropriately; and more generally, supporting a market-friendly business environment. In this report, these policies are not geared toward industrialization or the manufacturing sector, but encompass all sectors of the real economy, including the primary and service sectors.

Figure 1.3 Productivity Gap Relative to the United States

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Fernandez-Arias (2014).

PDPs are important for the economic development of all countries in the region. However, some countries may benefit from them more than others and some policy areas may be more important than others depending on country circumstances. Country heterogeneity in the region implies that uniform policy priorities are bound to be inadequate; in fact, policies that are appropriate in a given country may not work in another. The report emphasizes principles for policy and institutional design that can be useful under a wide range of country circumstances, more than explicit prescriptions for policies and agencies that may be maladapted to the specifics of particular countries. However, while the effort to collect detailed country data in this report made possible a thorough assessment of many policies and programs, relevant information for some countries remains a challenge to overcome in the future. In order to offset the lack of comprehensive and comparable data for all countries, in-depth information obtained from numerous country studies conducted in the region was also utilized whenever possible.

The report strongly emphasizes the need for sufficient institutional capabilities to conduct effective policies, particularly for policies that may involve risks. Some of the policies discussed will become progressively viable as countries reach more advanced stages of development and get farther along in building their institutional capabilities to successfully attempt high-impact policies soundly and safely. The report provides a road map for building capability to enable countries to advance in their path toward more effective PDPs.

The report is motivated by the region’s development challenges but does not view the poor outcomes as a license for remedial policies. Crucially, a poor outcome—for example, the realization that firms invest too little in research and development (R&D) compared to those in other regions—is not in itself a valid justification for policy intervention. Effective policy needs to make sure that poor outcomes are actually caused by market failures; then policy must be designed to address the root failures, rather than superficial symptoms.3 Governments have attempted and continue to attempt to deal with these serious productivity shortfalls through various policies, but not always with clarity, and sometimes in a wrongheaded fashion. Furthermore, even policies that may be justified because of market failures may turn out to be counterproductive in practice. As discussed later in the book, the market may fail to provide the right incentives to firms—for example, to innovate or to coordinate firms’ actions to secure collective inputs if profits are dispersed to free riders—but at the same time the government may fail even more if it intervenes, owing to issues such as capture by the private sector or political manipulation. In this context, it is fundamental to be mindful of the government capabilities required to conduct PDP effectively.

Thus, the report places particular emphasis on the proper conceptual justification of PDPs, not simply the will to achieve results. It is intended to help readers think about them as a way to address specific market failures. At the same time, it places emphasis on the institutional capabilities needed to derive the potential benefits from these policies while mitigating the risk of government failures.

As analyzed below, the region has a rich and long history of industrial policy from which to learn. While its experience includes some successes that did advance economic development, it is also filled with failures that discredited the effort. Eventually, there was a push to dismantle the structures of industrial policy as a liberalizing paradigm emerged from the macroeconomic crisis of the 1980s. While this new paradigm contributed a good number of sound recommendations that paved the way for better macroeconomic policies throughout the region, so far it has not been sufficient to foster productivity and growth to satisfactory levels. While distorted industrial policy and public-sector overreach was a very serious problem, wholesale elimination of industrial policy was not the solution. Today’s rethinking of productive development is not backtracking but rather moving forward, searching for different approaches to solve the growth problems that continue to dog the region. This requires sound policies and institutions based on new ideas and new evidence from policies within and outside the region. It also requires an understanding of what went wrong, not in order to reassess the past, but rather to make sure that new solutions avoid the same mistakes.

The rest of this chapter reviews in more detail some of the key components of the rethinking that this book proposes. The next section reviews the region’s experience with industrial policy, the subsequent liberalizing backlash against it, and the unsatisfactory growth performance of both strategies. Against this background, this report proposes to rethink the challenges and policy responses with conceptual clarity and a pragmatic approach, learning from experience. The approach taken for this rethinking is outlined at the end of the chapter.

The analysis leads to a wide range of conclusions, both conceptual and practical, about desirable policy features and the institutional framework (agencies and processes) that support them. To help the reader interested in PDPs and institutions appreciate the breadth of topics analyzed in this report, the following questions provide a taste of the extensive menu of issues that inspired this research effort.

Policy Features

• Do policies to reduce the cost of starting a business attract the right type of firms?

• Should countries rely more on subsidies or tax incentives as a way to foster business innovation?

• How can pioneers be rewarded in order to maximize productivity gains at the national level?

• Does it make sense to subsidize new technological equipment?

• How should the private sector be involved in labor training policies?

• Do immigration policies have a role in PDPs?

• How can countries stimulate the emergence of new export activities?

• What to look for when attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) and connecting to global value chains?

• Does it pay to have special programs for small or young firms?

• Should credit promotion policies rely on guarantees, loans, or grants?

• Should the provision of public inputs for clusters be conditional on beneficiaries sharing the costs?

• How should the PDP mix change as countries develop?

Institutional Framework

• Why is the “best practices” approach to PDPs flawed?

• What role does experimentation play in PDPs?

• Does impact evaluation really measure policy effectiveness?

• How can development banks be propped up to be more effective and safe?

• How do countries accumulate technical, operational, and political (TOP) capabilities to carry out PDPs?

• How can the public sector organize in order to ensure needed interagency cooperation for PDPs of wide scope?

• What kind of public-private interaction is more effective to design and implement PDPs?

• What mechanisms can be set up to encourage more collaboration and less capture from the private sector?

• How can a country set up a process to identify sectors worth supporting?

Industrial Policy Past and Present: Black Sheep or Sacrificial Lamb?

The development challenges of the region are not new and have been actively confronted by industrial policy. The current state of PDPs in the region, to a large extent, has been shaped by its history.4 The shock of the Great Depression was enormous. In the region as a whole, between 1929 and 1932, export volume shrank by over 25 percent, while the purchasing power of exports fell by 40 percent; meanwhile, since international financing was unavailable, import volumes contracted by over 60 percent (Bértola and Ocampo, 2012). Eventually, the shortage of manufactured goods, accompanied by a variety of measures to economize on imports and balance external accounts in the face of unprecedented declines in export values (quantitative restrictions, the abandonment of fixed exchange rates, and the ensuing real depreciations), resulted in a strong process of unintended, and largely welcomed, industrialization. During World War II, the unavailability of imports continued to give a boost to domestic manufacturing. It was only after the war that trade policy was used more deliberately with protectionist intent. The economic strategy that willy-nilly emerged during this period had a number of elements, of which import restrictions played a central role.

The import-substitution industrialization (ISI) that started in the early postwar period in the mid-1940s both within and outside the region was an attempt to solve the market failures that worked against productive transformation, against the backdrop of the historical conditions of that period. Policymakers had to address market failures in the context of weak and risk-averse domestic private sectors, rudimentary capital markets, international financial market disintegration, and shrunken levels of international trade. Developed economies emerged from World War II with average tariffs on imports of around 40 percent, which were reduced only gradually through subsequent internationally negotiated “rounds” of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) ending 50 years later. The solution attempted under these conditions was to pursue ISI through trade restrictions and other state-directe...