This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

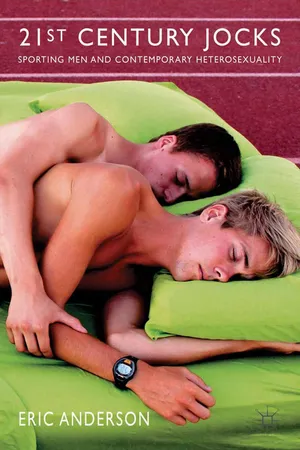

21st Century Jocks: Sporting Men and Contemporary Heterosexuality

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Drawing on hundreds of interviews with 15-22 year old straight and gay male athletes in both the United States and the United Kingdom, this book explores how jocks have redefined heterosexuality, and no longer fear being thought gay for behaviors that constrained men of the previous generation.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access 21st Century Jocks: Sporting Men and Contemporary Heterosexuality by E. Anderson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Regional Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

20th Century Jocks

1

Birth of the Jock

The purpose of this chapter is to explain to the reader why we once valued organized, competitive, and combative team sport in Western cultures (i.e., American football, rugby, soccer, etc.) and how that value has changed. I begin by highlighting that organized sport emerged at a particular historical moment in the West. It was a time in which culture was rapidly changing as a result of industrialization. Simultaneously, society was gradually recognizing that homosexuality existed as an immutable, unchangeable characteristic. This led to a turn-of-the-20th-century moral panic; a fear emerged that young men were becoming weak, soft, feminine and thus homosexual. Sports were adopted at this time because they were thought not only to build positive attributes in young men’s (and now women’s) lives that were useful in an industrial economy (like notions of sacrificing for the family/team or being complicit to authority), but also to be vital in turning young men away from softness, weakness, and homosexuality. Combined with Christian dogma, sport became a vessel for male youth to prove they were heterosexual.

I will then show that, a century later, sport still maintains an underserved esteemed social status. The purposes for which we engage with it have radically changed. We now think sport is necessary, no longer to teach complicity to authority, but instead to teach teamwork. Instead of using sport to heterosexualize male youth, today we use it in an attempt to ward off obesity. Thus, competitive, organized, violent team sports still reserve a mythical place in our cultural perspective—even if this merit is entirely unearned (see Anderson 2010a).

More importantly, this chapter also provides the explanation of how men’s masculinity became entangled with men’s (supposed) heterosexuality; and how the expression of femininity among men became associated with men’s homosexuality. It argues that, because homosexuality is not easily identifiable (unlike race, sex, or age), heterosexual men (and gay men who desired to be thought heterosexual) found hyper-masculinity as a mechanism by which to prove their social status as heterosexual—cementing homophobia into masculinity as well. This, then, is a chapter about old-school ways of thinking on masculinity, sexuality, and sport.

The Impact of the Industrial Revolution on Sporting Masculinity

Although the invention of the machinery and transportation necessary for industrialization began early in the 1700s, the antecedents of most of today’s sporting culture can be traced to the years of the second Industrial Revolution—the mid-1800s through early 1900s. During this time farmers replaced their farm’s rent for that of a city apartment instead. The allure of industry, and the better life it promised, influenced such a migration that the percentage of people living in cities rose from just 25 per cent in 1800 to around 75 per cent in 1900 (Cancian 1986).

However, just as cities attracted people, the increasing difficulty of rural life also compelled them to leave their agrarian ways. This is because the same industrial technologies that brought capitalism also meant that fewer farmers were required to produce the necessary crops to feed a growing population. With production capacity rising, and crop prices falling, families were not only drawn to the cities by the allure of a stable wage and the possibility of class mobility, but were equally repelled by an increasingly difficult agrarian labor market and the inability to own land (Cancian 1986).

For all the manifestations of physical horror that was factory life before labor laws, there were many advantages, too. Families were no longer dependent on the fortune of good weather for sustenance, and industry provided predictable if long working hours. Having a reliable wage meant that a family could count on how much money they would have at the end of the week, and some could use this financial stability to secure loans and purchase property. Also, the regularity of work meant that between blows of the factory whistle, there was time for men to play. The concept of leisure, once reserved for the wealthy, spread to the working class during this period (Rigauer 1981). It is the impact of this great migration that is central to the production of men’s sport in Western cultures.

Sport maintained little cultural value prior to the Industrial Revolution. Social historian Donald Mrozek (1983) wrote:

To Americans at the beginning of the nineteenth century, there was no obvious merit in sport…certainly no clear social value to it and no sense that it contributed to the improvement of the individual’s character or the society’s moral or even physical health.

However, by the second decade of the next century these sentiments had been reversed (Miracle & Rees 1994). Sport gave boys something to do after school. It helped socialize them into the values thought necessary in this new economy, and to instill the qualities of discipline and obedience of labor that was necessary in the dangerous occupations of mining and factory work (Rigauer 1981). Accordingly, workers needed to sacrifice both their time and their health, for the sake of making the wage they needed to support their dependent families.

In sport, young boys were socialized into this value of self-sacrifice, asking them to do so for the sake of team victory. As adults, this socialization taught them to sacrifice their health and well-being in the workplace for the sake of family. Most important to the factory owners, however, workers needed to be obedient to authority. This would help prevent them rebelling or unionizing. Sports taught boys this docility to leadership and authority. Accordingly, organized competitive team sports were funded by those who maintained control of the reproduction of material goods.

Spontaneous street-playing activities were banned, and children’s play was forced off the streets and into parks and playgrounds where children were supervised and their play structured. In the words of one playground advocate (Bancroft 1909: 21), “We want a play factory; we want it to run at top speed on schedule time, with the best machinery and skilled operatives. We want to turn out the maximum product of happiness.” Just as they are today, organized youth sports were financially backed by business, in the form of “sponsors.” Today, as part of a compulsory state-run education, they are also backed by the state. This is an economical way of assuring a docile and productive labor force. Sport teaches us to keep to schedule, under production-conscious supervisors (Eitzen 2000).

This shift to industry had other gendered effects, too. Although there was a gendered division of labor in agrarian work, there was less gendering of jobs and tasks compared to industrial life. Here, both men and women toiled in demanding labor. Accordingly, in some aspects, heterosexual relationships were more egalitarian before industrialization. Factory work, however, shifted revenue generation from inside the home to outside. Mom’s physical labor no longer directly benefited the family as it once did, and much of women’s labor therefore became unpaid and unseen. Conversely, men’s working spaces were cold, dangerous, and hard. Men moved rocks, welded iron, swung pick axes, and operated steam giants.

These environments necessitated that men be tough and unemotional. Men grew more instrumental not only in their labor and purpose, but in their personalities, too. As a result of industrialization, men learned that the way they showed their love was through their labor. Being a breadwinner—regardless of the working conditions in which one toiled—was a labor of love (Cancian 1986).

Furthermore, because women were mostly (but not entirely) relegated to a domestic sphere, they were reliant upon their husband’s ability to generate income. Thus, mostly robbed of economic agency, women learned to show their contribution through emotional expressiveness and domestic efficiency. Cancian (1986) describes these changes as a separation of gendered spheres, saying that expectations of what it meant to be a man or a woman bifurcated as a result of industrialization. Accordingly, the antecedents of men’s stoicism and women’s expressionism were born during this period.

But was sport truly necessary to teach young boys and men the values of industrial life? Before labor laws, children were permitted to enter the workforce well before puberty. Would they not just learn these values of toughness, sacrifice, stoicism, and courage in the workplace anyhow? Was sport really necessary to accomplish this? The answer is, no. Not entirely. We learned to value sport for yet another highly influential reason as well.

20th Century Masculine Moral Panic

During the Industrial Revolution, fathers left for work early, often returning home once their sons had gone to bed. Because teaching children was considered “women’s work,” boys spent much of their days (at school and home) socialized by women. Here, they were thought to be deprived of the masculine vapors supposedly necessary to masculinize them. Rotundo (1993: 31) writes, “Motherhood was advancing, fatherhood was in retreat…women were teaching boys how to be men.” A by-product of industrialization, it was assumed, was that it risked creating a culture of soft, weak, and feminine boys. Boys were structurally and increasingly emotionally segregated from their distant and absent fathers. This set the stage for what Filene (1974) termed a crisis in masculinity.

Adding to men’s fears, simultaneous to this was the first wave of women’s political independence (Hargreaves 2002). The city provided a density of women that made activism more accessible. Smith-Rosenberg (1985) suggests that men felt threatened by the political and social advancements of women at the time. Men perceived that they were losing their patriarchal power. The antidote to the rise of women’s agency largely came through a re-masculinizing of men; and this was facilitated by sport.

These tropes about the birth of 20th century masculinity are well explored in the sport and gender literature. However, a much under-theorized influence on the development and promotion of sport at this time comes through the changing understanding of sexuality during this period, particularly concerning the growing understanding of homosexuality.

Agrarian life was lonely for gay men. One can imagine that finding homosexual sex and love in pastoral regions was difficult. Conversely, cities collected such quantities of people that gay social networks and even a gay identity could form. This coincided with a growing body of scholarly work from Westphal, Ulrichs, and Krafft-Ebing, early pioneers of the gay liberationist movement. These scholars sought to classify homosexual acts as belonging to a type of person; a third sex, an invert, or homosexual (Spencer 1995). From this, they could campaign for legal and social equality.

Previously, there were less entrenched heterosexual or homosexual social identities. In other words, a man performed a sexual act, but his sexual identity was not tied into that act. Under this new theorizing, homosexuality was no longer a collection of particular acts, but instead, as Michel Foucault (1984: 43) famously wrote, “The homosexual was now a species.” This, of course, meant that heterosexuals were now a separate species, too.

Sigmund Freud helped explain the creation of this “immoral” species (the homosexual). Fears emerged that an absent father (who was working in the factory) and an over-domineering mother (who was domesticated) could make kids homosexual. This created a moral panic among Victorian-thinking British and American cultures. It seemed that because industrialization pulled fathers away from their families for long periods of occupational labor, it had structurally created a social system designed to make boys gay.

Accordingly, in this zeitgeist, what it meant to be a man began to be predicated in the idea of not being like one of those sodomites/inverts/homosexuals. Being masculine entailed being the opposite of the softness attributed to homosexual men. Kimmel (1994) shows us that heterosexuality therefore grew further predicated in aversion to anything coded as feminine. Accordingly, what it meant to be a heterosexual man in the 20th century was to be unlike a woman. What it meant to be heterosexual was not to be homosexual. In this gender-panicked culture, competitive, organized, and violent team sports were thrust upon boys both as a wrongheaded way to sculpt them into heterosexuality, and to prove to others that they were not one of those reviled homosexuals. Essentially, sport became the cure for the feminizing and homosexualizing effects of industrial modernity.

Sport as a Masculine Cure-All to the Feminization of Men

It was in this atmosphere that sport became associated with the political project to reverse the feminizing and homosexualizing trends of boys growing up without father figures. Sports, and those who coached them, were charged with shaping boys into heterosexual, masculine men. Accordingly, a rapid rise and expansion of organized sport was utilized as a homosocial institution principally aimed to counter men’s fears of feminism and homosexuality.

Part of this political project was elevating the male body as superior to that of women. Men accomplished this through displays of strength and violence so that sports embedded elements of competition and hierarchy among men. Connell (1995: 54) suggests, “men’s greater sporting prowess [over women] has become…symbolic proof of superiority and right to rule.” But sport could only work in this capacity if women were formally excluded from participation. If women were bashing into each other and thumping their chests like men, men wouldn’t be able to lay sole claim to this privilege. Without women’s presence in sport, men’s greater sporting prowess became uncontested proof of their superiority and right to masculine domination. Thus, sport not only reproduced the gendered nature of the social world, but sporting competitions became principal sites where masculine behaviors were learned and reinforced (Hargreaves 2002).

Social programs and sporting teams were created to give (mostly white) boys contact with male role models. The Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) came to America in 1851, hockey was invented in 1885, basketball was invented in 1891; the first Rose Bowl was played in 1902; and the first World Series was played in 1903. By the 1920s track, boxing, and swimming also grew in popularity, and with much of the nation living in urban areas, America entered “the Golden Age of Sport”; the country was bustling with professional, semi-professional, and youth leagues.

Unfortunately, when we think of sport today few consider its origins and intent. Few recall that Pierre de Coubertin’s reinvention of the ancient Olympic Games was because he saw French men becoming soft, not because he wanted to unite the world’s nations.

Christianity also concerned itself with the project of masculinizing and heterosexualizing men during this period. Muscular Christianity concerned itself with instilling sexual morality, chastity, heterosexuality, religiosity, and nationalism in men through competitive and violent sports (Mathisen 1990).

This muscular movement aimed to force a rebirth of Western notions of manliness, to shield boys and men from immoral influences by hardening them with stoic coaches and violent games. Ironically, some of those pushing hardest for masculine morality began the YMCA, which almost immediately served as a gay pickup joint (something reflected in the Village People’s song “YMCA”).

This period of history also saw playful, less organized youth sporting practices co-opted by adults (Miracle & Rees 1994). Prior to the 1890s, sporting matches were controlled by students—they were coached by students, and organized and played by and for students. However, with new reasons for valuing sport, coaches were paid to manage sport. It was also during this time that recr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part I 20th Century Jocks

- Part II 21st Century Jocks and Inclusivity

- Part III 21st Century Jocks and Intimacy

- Part IV 21st Century Jocks and Sex

- Conclusions

- References

- Index