eBook - ePub

Learning from the World

New Ideas to Redevelop America

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In this far-ranging and provocative volume, Joe Colombano and Aniket Shah provide global perspectives on the most significant challenges facing modern America, seeking to inspire new ideas to redevelop America.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Learning from the World by J. Colombano, A. Shah, J. Colombano,A. Shah in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Public Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: A New Approach to Redevelop America

Joe Colombano and Aniket Shah

America needs new ideas.

For many reasons—ranging from technological diffusion to demographic shifts to political transitions—the country that indisputably ruled the latter half of the 20th century is no longer firmly in the lead. We believe this to be attributable to a lack of new ideas. For much too long America’s economy and society have relied on outdated models and failed to breathe new life into their workings. In the last decade, this has resulted in a relative decline in America’s performance and influence on the world stage.

America must look beyond its borders for inspiration. Many countries around the world have seen unprecedented progress in the last decades. Far from being just trade partners or market competitors, these countries provide lessons to address major challenges currently facing the United States, from macroeconomic stabilization to financial reform to social betterment. Learning from the world is not an exercise in humility triggered by the deepest economic crisis since the 1930s, but a smart strategy for future competitiveness.

New ideas are needed regardless of current economic junctures. As this volume goes to press, an increasing number of commentaries forecast a comeback for America’s industry, for example on the back of a potential energy boom. By contrast, many of the emerging markets, including China, India, and Brazil, have entered cyclical slow-downs. Beyond economic cycles, however, there are important lessons for the US to learn from these countries on how to overcome structural challenges.

This volume examines how America can adjust to new economic realities. Countries around the world are facing common challenges—mainly, how to deal with the opportunities and risks brought about by a highly interconnected, multipolar global economy. By considering successful policies, models and case studies from around the world, we believe new ideas can be found to redevelop America.

* * *

The debate over the state of the US economy and the perceived fading of its primacy is not new. Much has been written on the topic, increasingly so in the wake of recent financial turmoil and volatility. The arguments have generally unfolded along two opposing views: on the one hand, pessimists argue that the US has seen its greatest days and that its prospects are now tainted by pervasive internal sclerosis and fierce external competition. On the other hand, optimists maintain that the exceptionalism of the American case makes it resilient to both internal and external challenges in the long term. Somewhere in the middle, others remain the “realists,” who maintain that the combined challenges of internal and external factors may lead to a sort of aurea mediocritas in which the US would likely cease to be the unchallenged economic leader in the world and, yet, the sun would not entirely set on its empire: in the middle to long run, the realists argue, the US economy would remain among the top economies of the world, its relative position fluctuating with the national economic cycle and global macroeconomic trends.

Despite the appeals of each argument, this book is not concerned with arguing for any of these three positions. We do believe that the realists’ position is the most likely, that competitive pressures have grown higher over time, many economies have caught up with America, and one—China—is likely to soon overtake it as the largest in the world. At the same time, we believe that America’s role will remain important owing to, among other factors, the size of its economy, the entrepreneurship of its people, the technological innovation of its businesses, and the reach of its influence. However, we also believe that much of the success that the US has had in its recent past—both as an economy and a society—is the result of important decisions made decades ago. For way too long the American political class, tied up as it is with bi-annual electoral cycles and exhausting checks-and-balances processes, has been unable to deliver the sort of leadership needed to shape a bold vision for the new millennium and take the country forward.

While the American malaise is the backdrop against which this book is set, it is not what this book is about; not directly at least. This book is about generating new ideas. We acknowledge that an American malaise exists, but we do not claim to be able to offer a complete diagnosis of it, least of all to be able to prescribe one specific cure. Rather, we aim to offer a broad selection of ideas as possible medicines, both traditional and alternative, for consideration in the national debate, in the belief that this may contribute to treating the malaise and, ultimately, restore America’s now fading glory.

Our motivations for this volume of edited contributions come from the realization that much has happened outside the borders of the United States in the last decade, much of it offering worthy and relevant ideas, and yet most of it is rarely discussed as a viable alternative for the US. Pessimists, optimists, and realists alike focus on external threats or inner causes and symptoms of the American malaise, but they have not broadened their thinking to seriously consider if the experiences of other countries have anything to offer the United States. For all of America’s claims to open-mindedness and multiculturalism, the national debate—be this within its government, corporate sector, or citizens—remains inward-looking in the belief that solutions to America’s problems need to be found in America. It is this sort of isolationism, which is often combined with a measure of complacency and, at times, perceived as arrogance, that we believe to be most damning for the prospects of the US economy. Our intent, therefore, is to provide a systematic review of successful policies undertaken overseas, discuss their requirements and relevance to the American case, and offer them as contributions to the national debate on the future of the American economy.

This volume will inevitably revive the longstanding debate amongst historians, political scientists, and economists over the notion of “American exceptionalism.” The discussion of whether America is an “exceptional” nation has been at the heart of America’s self-identity since the 17th century. Starting from John Winthrop’s assertion of the Massachusetts Bay colonies serving as a “City upon a hill,” in 1630, prominent intellectuals, from Alexis de Tocqueville to Samuel Huntington, have made the case that America plays a unique and, indeed, “exceptional” role in the world’s affairs, stemming from its values, political system, and history.

The debate over American exceptionalism is essential to engage with if one is to understand the current American malaise. It is the notion of American exceptionalism that has underpinned much of American foreign policy of late and also America’s lack of willingness to adopt international best practices in public policy. This volume, however, does not intend to take a position on whether America is an exceptional country, as that debate has received much attention from many scholars over the years. Instead, this volume aims to convey the editors’ belief that exceptionalism should not be confused with excellence. For America to remain a country of economic and political excellence, it should redouble its effort to listen to, and incorporate, best practices of other nations around the world into its own policies. Exceptionalism, or excellence, cannot occur if America is to live in intellectual isolation.

* * *

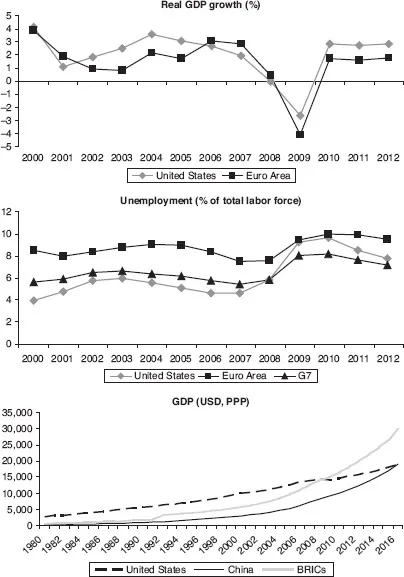

That an American malaise exists is a fact, not an opinion. Incontrovertible data, including from official US sources, points to it (Figure 1.1).

The picture is especially bleak in the wake of the 2008–9 global crisis, but the trend for most of the past decade has been equally worrying. Real growth in the 2000–12 period has averaged 2 percent, only marginally better than the rate in the Euro Area, and significantly lower than in the previous two decades. At the same time, the US labor market, once praised for its flexibility and as one of the competitive advantages of the US economy, has suffered remarkably: unemployment, including long-term unemployment, has increased to worrying levels, above the average of other advanced economies and close to European averages. Lacking a social safety net, weak growth and higher unemployment rates have resulted in an increasing number of Americans being left behind as the poverty rate climbed from around 11 percent in 2000 to 15 percent in 2011. The American dream remains a dream for a staggering 46.2 million people in 2011, the highest number of poor in the country since the US Census Bureau started collecting data on poverty in the late 1950s.1

Figure 1.1 The American malaise: symptoms

Source: data from IMF, World Economic Outlook, 2012.

At the same time, the rest of the world is catching up. In the last decade, the pace of growth of emerging economies was three times as fast as that of the US. As a result, in the space of only ten years, the aggregate size of the economies of Brazil, Russia, India, and China has increased from one-sixth of the world economy to one-quarter. Meanwhile, the share of the American economy in the world shrunk from about one-quarter to one-fifth by the end of the decade.

Certainly, world economic growth is not a zero-sum game, and US companies greatly benefit from the rapid expansion of emerging markets through corporate profits and employment in US multinationals, as well as their supply chains and other positive transmission effects.2 But the point here is about the pace and magnitude of catch-up of emerging countries relative to the US. Combined data on income per capita, life expectancy, and population size provide a compelling picture of the formidable jump that countries like China, India, and Korea have made in the past three decades, and even more so relative to the US.3 Projections for the short to medium term confirm such a trend. The general consensus is that emerging markets will be the key drivers of the global economy in the 21st century.

The downgrade of the US credit rating in 2011 provides further evidence of a pervasive American malaise. Booted from the triple-A club, the US is now double-A-plus rated, on a par with France and Austria and in the same high grade category with other double-A sovereigns such as China, the Czech Republic, and Estonia, among others. The problem is one of perception: much of US success is built on its reputation for being the strongest economy in the world, and that US Treasury bills are the safest place to put your money. The US has been able to run a large current account deficit on the back of such a reputation, which for years contributed to a positive net international investment position. Further to the downgrade, there are now 19 countries that are perceived to be a safer harbor for investors’ money than the US.4

Symptoms of an American malaise are not only economic; the ailments of the “sick man of the West” reach deep into the social sphere. International comparisons make this especially clear. According to the latest CIA World Factbook, the US ranks 51st in the world in terms of life expectancy.5 America ranks 14th in the world on Gallup’s Life Satisfaction ranking; out of 21 countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) it ranks 17th for Child Wellness. The US is in 3rd place on the world ranking of the 2013 United Nations’ Human Development Index, but drops to 12th when the index is adjusted for inequality.6 The US ranks 42nd on the UN Gender Inequality Index, on a par with Hungary and Malaysia.7 Transparency International puts the US in 19th place on its 2012 Corruption Perception Index, below Barbados and just one place above Chile and Uruguay.8 US performance on the international assessment of education proficiency is similarly disappointing: America ranks 14th in the world in the latest OECD PISA Rankings for Reading, 25th in Mathematics, and 17th in Science. America ranks 13th in the world with its proportion of 25–34 year olds with at least an associate degree (OECD).9

Certainly, the relative position of the US on international assessments is also the result of the progress made in the rest of the world, but the fading of America’s former primacy is undoubted. Infrastructure is an example. As any new visitor to New York has experienced, cell phone signal coverage in Manhattan is at best inadequate. Houston, the sixth largest metropolitan area in the country, has had rolling blackouts to cope with a struggling grid unable to accommodate peaks of demand in the summer. The country’s highways and airports are in great need of repair and renovation. The Interstate 35W Mississippi River eight-lane bridge in Minneapolis, Minnesota collapsed during rush hour in 2007. Every year, the hurricane season shows the vulnerability of America’s infrastructure and the inability of the American construction industry to cope with the elements. As indicated by Skidelsky and Martin in this volume, in 2009 the American Society of Civil Engineers estimated investment needs over the next five years alone of $2.2 trillion. American infrastructures for aviation, energy, hazardous waste, roads, levees, schools, and transit were rated D or D–.

That America is falling behind is not merely anecdotal evidence. Every year, the Global Competitiveness Report issued by the World Economic Forum (WEF) ranks countries on the basis of a Global Competitiveness Index (GCI), a composite index calculated from both publicly available data and annual surveys of business leaders. The index aims to measure national competitiveness, defined as the set of institutions, policies, and factors that determine the level of productivity of a country, and is based on detailed measures of competitiveness grouped in 12 pillars: institutions, infrastructure, macroeconomic environment, health and primary education, higher education and training, goods market efficiency, labor market efficiency, financial market development, technological readiness, market size, business sophistication, and innovation....

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Introduction: A New Approach to Redevelop America

- Part I Macroeconomic Challenges

- Part II Institutional Framework and Policy Tools

- Part III Infrastructure, Innovation, and Competitiveness

- Part IV Social Policies

- Part V Policy and Values

- Conclusion

- Index